The user-centric licensing debate has so far been largely focused on its potential impact on recording artists and labels, but how would music publishers fare under this new model? Eamonn Forde looks at the discussion so far and the obstacles preventing this idealistic system from being implemented.

The idea of user-centric licensing in regard to streaming services been debated on the fringes of the business for years, but three key events in the past year have given it a dramatic boost back up the industry agenda.

Last April, Deezer announced it was looking into paying out royalties on a user-centric licensing basis, the first major streaming service to do so.

Then in November, the Finnish Musicians’ Union teased early findings of research it was involved with that looked into the economic implications of this model, following up with more details at the by:Larm conference in Oslo at the start of March this year.

And in February, details emerged of what has become known as “the Bulgarian scam” where multiple premium accounts on Spotify were set up and the same limited number of tracks, supposedly uploaded by the scammers involved, were played on repeat, generating upwards of $1m in royalties that far exceeded the cost of setting up the premium accounts involved. This prompted Annabella Coldrick, chief executive of the Music Managers’ Forum in the UK, to post a blog on Medium arguing that this would have been impossible under a user-centric licensing model.

But what exactly is user-centric licensing and how does it apply to music streaming services?

In short, the current licensing model for all the major streaming services is commonly described as working on an “airplay model”. In this system, all the money generated from subscriptions, minus the service’s cut (of around 30%), goes into a central pot and is then apportioned out according to share of total plays by the artists across the entire service.

One argument against this model is that it rewards the already successful and penalises the niche. To boil it down to its most basic level, let’s work through an example. You subscribe to [name of your favourite subscription streaming service here] and pay £9.99 a month for it. This month you listened to ‘Hit The North’ by The Fall 999 times and ‘God’s Plan’ by Drake just once. It does not follow that 99.9% of the remaining £7 from your subscription (after the service takes its cut) goes to Beggars Banquet on the label side (to apportion to the recording artists as per their contract with the label) and, on the publishing side, to the estate of Mark E Smith as well as Brix Smith and Simon Rogers (as the listed writers). Under the current system, if Drake accounted for 5% of all streams on the service across all its users that month, he (plus his label and co-writers) would get 5% of your £7, not 0.1%.

It is surely a no-brainer to implement this immediately and start paying out royalties on this model, right? Before we get to that, there are some concrete numbers to work through and some wider points to consider.

To try and make sense of this in monetary terms, the Finnish study mentioned above (pulled together by the Finnish Music Publishers’ Association, the Musicians’ Union, the Finnish Society Of Composers & Lyricists, and the Society Of Finnish Composers) looked at 10,000 tracks that clocked up 22,496 plays from 4,493 acts across 8,051 users. They found that close to 90% of these 4,493 artists were only getting a handful of streams each, another 10% had streams in the dozens while the top 0.4% of acts accounted for the lion’s share of streams.

Under the current system, the elite 0.4% took 10% of total revenue across all 8,051 users; but if it was measured under a user-centric model, they would have taken 5.6%.

“The difference between the two models is [that] it’s clear that pro-rata favours these few at the top of the pyramid,” is how Lottaliina Pokkinen of the Finnish Musicians’ Union summarised it. The researchers were quick to point out that not every small act under this system would see a huge financial windfall and may actually get less money, but the ultimate impact would see the very biggest earners, those right at the tip of the pyramid, relinquishing at least some of their money to acts smaller than them.

At the moment, it’s all a series of hypotheticals stacked on top of each other, but the debate is gaining momentum.

“The ultimate impact would see the very biggest earners, those right at the tip of the pyramid, relinquishing at least some of their money to acts smaller than them.”

That said, the whole system has tended to be explained in terms of the impact of this on recording artists and labels rather than songwriters and publishers. Of course, the bulk of streaming money goes to labels and so it makes sense to look at how the biggest share could be apportioned out. (It is estimated that on Spotify in Europe, between 55% and 60% goes to labels while between 10% and 15% goes to publishers, with Spotify taking the other 30%.)

When we start to apply it all to publishing payments, however, things start to get really complicated. Sometimes the recording artist is the writer; other times they are recording someone else’s composition; and, particularly if we look at the top 40, there will be teams of writers focusing on different elements of the song such as the choruses and topline melodies, of which the performer might be just one of several writers.

Looking at, by way of example, Spotify’s 10 biggest streams of last year, in writer terms they break down as follows.

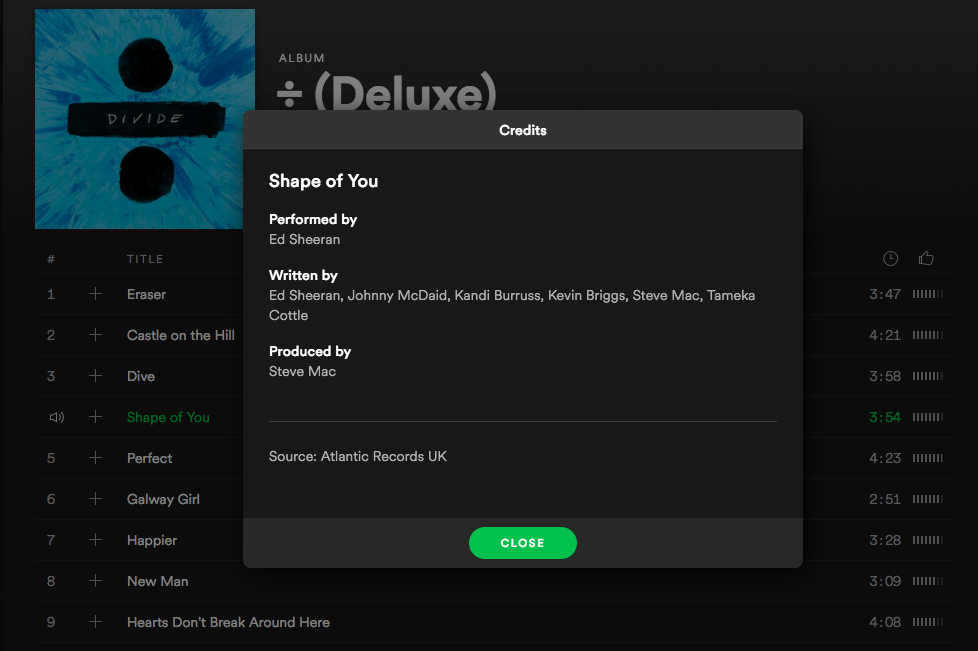

- ‘Shape Of You’ by Ed Sheeran (six writers, including Sheeran)

- ‘Despacito’ (ft Justin Bieber) – Luis Fonsi & Daddy Yankee (three writers, including Fonsi)

- ‘Despactio’ – Luis Fonsi (three writers, including Fonsi)

- ‘Something Just Like This’ (ft Coldplay) – Chainsmokers (five writers, including all of Coldpay and Andrew Taggart from Chainsmokers)

- ‘I’m The One’ (ft. Justin Bieber, Quavo, Lil Wayne and Chance The Rapper) – DJ Khaled (seven writers, including DJ Khaled)

- ‘Humble’ – Kendrick Lamar (three writers, including Lamar)

- ‘It Ain’t Me’ (ft. Selena Gomez) – Kygo (five writers, including Kygo and Gomez)

- ‘Unforgettable’ (ft. Swae Lee) – French Montana (five writers, including Montana and Lee)

- ‘That’s What I Like’ – Bruno Mars (eight writers, including Mars)

- ‘I Don’t Wanna Live Forever’ – Zayn & Taylor Swift (three writers, including Swift)

On a label level because of the multiple performer issues, processing that on a user-centric basis is going to be Byzantine enough – but this seems a mere bagatelle compared to what it means for the publishing and how writers will share under this new system.

The problem with all of this thinking and the good intentions underpinning it is that it presumes that the royalty payment systems for streaming revenue work flawlessly. Which, as any publisher will tell you, is far from the case, with metadata still being a mess. There is no unified metadata database and mechanical payments are often held back or fall through the cracks somehow.

“The problem with all of this thinking and the good intentions underpinning it is that it presumes that the royalty payment systems for streaming revenue work flawlessly.”

Back in 2015, Billboard was reporting that up to 25% of mechanical royalties due to publishers and songwriters were not being paid through due to identification issues and the situation has not really improved much since then. “The labels are reporting 5m streams for a song to an artist/songwriter, while the publishers will only show 4m streams,” GSO Business Management director of royalties Steven Ambers told the publication at the time. “The publisher should always show more transactions than the master recording because of cover versions, but so far it is not happening in the streaming world.”

The RIAA has just reported that paid streaming made up 47% of all recorded music revenue last year and was the major factor in pushing up “estimated retail value” in the world’s biggest music market by 16.5% to $8.72bn. With streaming becoming the dominant format, these problems are only going to become exacerbated.

The whole situation, if anything, has worsened rather than improved and in recent months services like Apple Music and Spotify have found themselves facing down major lawsuits in the US over alleged unpaid mechanicals. This is a rolling problem for them, with Spotify having had to pay out $30m to the National Publishers’ Association in 2016 for outstanding royalties and, in May last year, paying out $43m to settle another publisher-led suit.

If services are already groaning under the pressure of complex royalty accounting for publishing under the current system, one can only imagine how more Sisyphean this could become under a user-centric model when it comes to mechanicals.

“If services are already groaning under the pressure of complex royalty accounting for publishing under the current system, one can only imagine how more Sisyphean this could become under a user-centric model when it comes to mechanicals.”

This is all impaired by the fact that services themselves appear resistant to the user-centric model (apart from Deezer, and it still has to move beyond the investigative/trial stage) and the cost of processing and auditing billions of micropayments is seen by some as prohibitively expensive. At least for now.

Maybe it could work and maybe it could mean that smaller writers – especially those who are not recording artists or performers themselves – could benefit enormously. It might also mean that niche genres find themselves at a greater financial advantage from this as money starts to trickle down from the top 1% (or, more specifically, the top 0.001%) who, by their sheer size, are sponging up perhaps more cash than those at the bottom of the revenue pyramid feel they deserve.

If services can’t match publishing data to the writers under the current system, how on earth are they going to fare under the user-centric model?

Given the messy state of metadata and the apparent torpor with regard to actually fixing it, this all seems like a divine idea but one that currently lies maddeningly out of reach.