Barely a week goes by in the music industry without news of one artist suing another for copyright infringement. But are we really equipped to decide what constitutes plagiarism? Perhaps we’re simply running out of tunes? In the following post, data experts BMAT discuss the issue of melody scarcity and whether technology is the determining factor in detecting just how similar two songs really are.

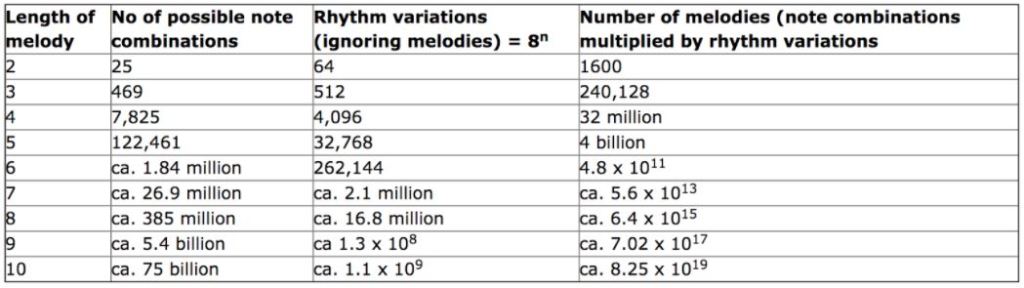

No matter how you represent a melody, as long as the representation uses limited and quantised metrics – like a music score over a certain number of bars does – the number of possible melodies is finite. Despite infinite expression nuances that relate with sound production and instrument attributes such as timbre, dynamics or transitions; the number of piano-roll melodies is finite, just like the number of possible sudokus is.

Excerpt of Oli Freke’s article in maths.org

As introduced in the previous chapter, not only the space of melodies is finite, but it is also de-facto compressed and heavily populated. Compressed because certain melodies, albeit possible, will hardly reach any audience – e.g. a dissonant tune or a melody outside audible ranges. And heavily populated because of the huge flux of music creation since the democratisation of music recording and distribution techniques- according to Frankel and Gervais, only in US alone around 80,000 albums are released every year.

“The space of melodies is finite, de-facto compressed and heavily populated”

A lifetime is not time enough for someone to listen to all music previously released – not even to all music released in the last decade. Individual music memory is, to say the least, very little, and if we consider how our brain cheats our conscience according to Kahneman, it is also very unreliable. This makes collective music memory a tiny and flaky window that constantly refreshes its view in a way popular releases are periodically forgotten. This would for example explain how come George Harrison wrote My Sweet Lord in the 70’s plagiarising the hit from the 60’s He’s So Fine. Subconsciously or not, our theory stands.

Back to the melodic space, the more new songs are released, the more crowded the space is, the more challenging it becomes to fill a blank – to come up with a genuinely original tune that does not resemble any of the pre-existing. And if we want the tune to be popular the even crazily tougher it gets – from previous chapter. In other words, if not today, tomorrow, if you want a catchy tune, copy or die.

“In other words, if not today, tomorrow, if you want a catchy tune, copy or die”

At BMAT, in collaboration with the MTG, we have been long working on a technology that is capable of detecting cover songs – including live performances, karaoke versions or remixes. In the 00’s we released our first version and got the attention of a technology giant willing to explore its use for user upload content copyright clearance. We started a joint project to explore the potential of our technology running real-life scenario tests.

Featured photo credit: Gavin Whitner