Slade made intentionally terrible spelling a calling card at the height of their fame, but a clumsy typo resulted in perhaps the most collectable piece of music merchandise of 2019. Lifting lyrics from her comeback single, Taylor Swift sold a shirt that proclaimed, “Your’e the only one of you / Baby that’s the fun of you.” It took a while, but fans eventually spotted the “your’e”/“you’re” mistake, although some began to tie themselves in knots to prove it was intentional and some sort of cryptic clue.

This not only raised the necessity of having someone check spellings on merchandise but also made clear just how important lyrics now are on a range of products from artists – going from T-shirts and jackets through to mugs, posters and greetings cards.

There are a lot of pop stars treating lyrics on products as powerful semantic hooks that trigger sonic connections – playing on the most memorable or catchy lines in a song that will implant the melody in the head of anyone who gets the reference.

There are a lot to choose from of late. There’s Queen with “Don’t stop me now I’m having such a good time” on the back of a Wrangler’s denim jacket. Or there’s Lil Nas X who has partnered with the same company, in a large part because of the “Cowboy hat from Gucci / Wrangler on my booty” lyrics in ‘Old Town Road’, showing these deals can be a two-way street.

Post Malone’s latest merchandise line is peppered with lyrics, as is Ariana Grande’s range with H&M. Kayne West has utilised lyrics from his new Jesus Is King album on his latest clothing items. Even Bob Dylan is at it with a section of handwritten lyrics from ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ on the front of a long-sleeve top. And who doesn’t want a polo cap with the title of Joy Division’s most famous song across the front?

The Beatles were doing this back in 2016 when Epic Rights got the global licence to develop products built around the words of the Lennon/McCartney songbook. “Those iconic lyrics, which double as cultural and historical references, also communicate attitudes that are as topical and relevant today as they were in the 1960s,” said Dell Furano, CEO of Epic Rights, on signing the deal.

More than just having an artist image or an album sleeve put on a variety of products, lyrics are increasingly part of the merchandise strategy. And that, of course, requires a licensing agreement with the publishers who were previously excluded from this gold rush as the record label, the artist, the photographer and the logo designer (depending on their own licensing agreements with each other and merchandise companies) made almost all the money here in the past.

This is all still an emerging area for the publishing business, according to Bruce New of CC Young, who previously worked at both EMI Music Publishing and Sony/ATV Music Publishing as a licensing manager. “That area of music licensing wasn’t as well established because there wasn’t a wide range of categories that could be licensed. If you went into H&M or another high-street store, you pretty much saw the album cover being used; but there wasn’t much use of lyrics five or six years ago.”

“That area of music licensing wasn’t as well established because there wasn’t a wide range of categories that could be licensed. If you went into H&M or another high-street store, you pretty much saw the album cover being used; but there wasn’t much use of lyrics five or six years ago.”

– Bruce New, CC Young

He says this was mainly down to garment production times that were rarely swift enough to capitalise on a song when it was a chart hit.

“Because of the lead time that’s involved in making a product, it could have been in and out of the chart before the actual product could be launched into the store,” he says. “[The garment manufacturers would] have to be given the lyrics, they would then design the layout, get the approval, get it manufactured and then get it into store. But that lead time could be anywhere between three and six months.”

Lyrics are increasingly seen as – and commercialised as – a type of trademarking and acts are keen to lock down their most hook-packed lyrics to ensure they, and no one else, can exploit them across a multitude of products.

There were some raised eyebrows in 2015 when Taylor Swift moved to trademark phrases like “this sick beat”, “party like it’s 1989, “‘cause we never go out of style” and others that were taken from her hits.

“Some of the more obscure – and likely obligatory – items covered by her trademarks include typewriters, walking sticks, non-medicated toiletries, Christmas stockings, ‘knitting implements,’ pot holders, lanyards, aprons, whalebone, napkin holders and the particularly ominous collection of ‘whips, harness and saddlery’,” mocked Rolling Stone at the time.

But fast-forward to this year and Lizzo was seeking to trademark “100% that bitch” (from her song ‘Truth Hurts’) to use in a variety of contexts, including on clothing items. As acts start to see the merchandising and branding opportunities here bear real fruit, not only will they move to trademark lyrical snippets, this will also bleed into the songwriting process where pithy and profound lines are woven into songs with one keen eye on the merchandising opportunities.

“As acts start to see the merchandising and branding opportunities here bear real fruit, not only will they move to trademark lyrical snippets, this will also bleed into the songwriting process where pithy and profound lines are woven into songs with one keen eye on the merchandising opportunities.”

Just as with streams, record sales, radio plays and sync use, all of this has to be properly tracked and accounted for. This is what New does at CC Young so he is able to offer insight from both the licensing and payment tracking side.

“Part of what we do is audit the contract [between licensor and licensee] and the statements that comes from that to ensure that the calculations are being made on the right rates and on the right products,” he says. “It might be that there’s a licensee who has got 10 different products. Because they’re in different categories – one might be a mug, one might be apparel, one might be homeware – there might be different royalty rates for each piece.”

He adds, “Part of what a royalty accountant would look at is that the calculations are being made on the right basis. And invariably you do find things that are paid or reported at the wrong rate. And it’s not necessarily a bad intention; it can just be a misunderstanding of the contract […] Auditing is fairly big for the big licensors. But for small publishers and small rights holders, they possibly don’t do it as much because they’re more worried about their relationship status with the licensees. But certainly the likes of Disney, Sony and Universal do it on a fairly regular basis because they are protecting their rights. And for them, if an audit does find a miscalculation somewhere, it could be worth quite a bit.”

The rise of retailers and platforms like Redbubble, Etsy and Not On The High Street have created new challenges and headaches for not just merchandise companies but also songwriters and publishers as they try to police what is being offered online that uses their copyrights but which might not be fully licensed (or even licensed at all).

“The rise of retailers and platforms like Redbubble, Etsy and Not On The High Street have created new challenges and headaches for not just merchandise companies but also songwriters and publishers as they try to police what is being offered online that uses their copyrights.”

At the end of 2019, The Pokémon Company International was awarded $1 in nominal damages from the Federal Court of Australia in a case against Redbubble for copyright infringement. “Many of the items sold through the Redbubble website involved a ‘mash up’ of images, such as the combination of Pikachu and Homer Simpson,” said Justice Pagone in his judgment. “The evidence thus did not support a confident finding of damages in the amount claimed.”

The use of lyrics in unlicensed products is, however, a different matter entirely. New suggests the bigger music companies are better set up to monitor this and can quickly swing into action to have unlicensed products removed from high-street shops or online stores.

“I would say that the smaller labels and the smaller publishers have a bigger problem when trying to face that kind of thing,” he says. “They literally look at it and think it’s a huge website and there might be stuff on eBay, Amazon or Not On The High Street and they think how the hell are they going to tackle that.”

It can be a mixed bag when taking action against rogue operators here, some genuinely unaware they are unlicensed and others feigning ignorance.

“When I’ve had to approach people in the past, they have been quite unaware that they needed a licence; but it is debatable as to whether they were aware of it or not,” says New. “The majority of them are receptive to then taking down the product from their site, declaring what they have produced and then paying a royalty for it.”

There are, however, steps being taken here to tighten things up and make the licensing of lyrics onto products by a range of small companies that little bit more straightforward.

In November, LyricFind’s merchandise arm LyricMerch struck a deal with eBay to allow the selling of clothing and other products built around song lyrics. “eBay is a trusted online platform for customers looking for unique gifts and niche items, which is what LyricMerch offers,” said LyricFind/LyricMerch founder and CEO in a press statement on the deal. “Having our products available on eBay and their global shoppers allows us to lean into a marketplace that already caters to our target audiences, making this a natural partnership.” He added, “Licensing a lyric means more than just using it with permission. When you purchase a LyricMerch T-shirt or mug, your purchase earns money for the writers and teams behind the lyrics.”

While there are a number of songwriters – among them Kate Bush, Neil Tennant and Lou Reed – who have had their lyrics issued in collected volumes in recent years (sitting alongside collections from the likes of Bob Dylan, Ian Dury and Joni Mitchell), the rise of music-centric children’s books has created new opportunities and threats.

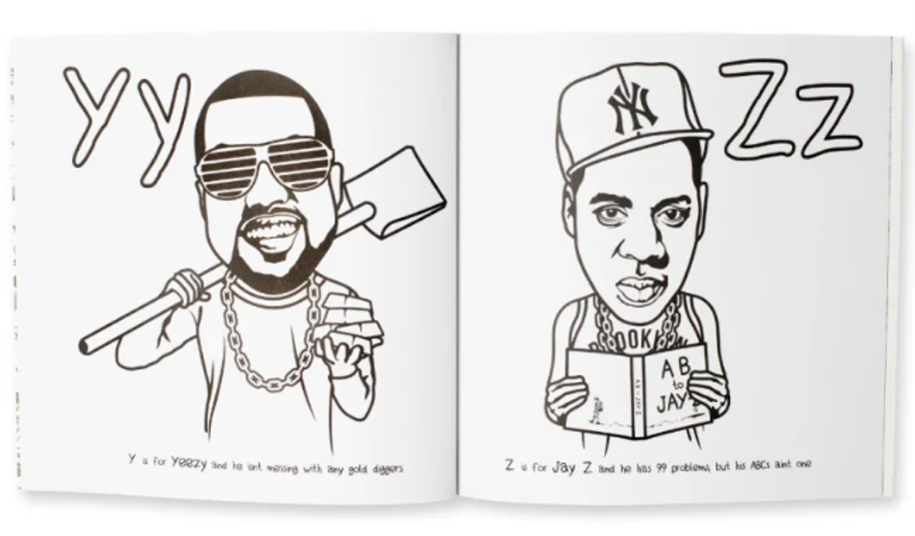

The Baby Rocker series has books based around David Bowie and Kiss, but Australian online retailer The Little Homie ran into problems earlier this year with its A B To Jay-Z book. It contained lyrics such as, “If you’re having alphabet problems I feel bad for you son, I got 99 problems but my ABCs ain’t one.” Jay-Z took legal action against the company, claiming copyright infringement and trademark infringement as well as unauthorised use of his name, his likeness and (as the quite above shows) lyrics from his ’99 Problems’ track.

The complaint is arguing all of this is “a deliberate and knowing attempt to trade off the reputation and good will” of Jay-Z and an abuse of his IP “for their own commercial gain”. It also argued it was making a “false and misleading representation” that the rapper was associated with the book. The Little Homie also has books based around 50 Cent and Notorious BIG, but so far the Jay-Z case is the only one against the company.

Such books might help kids with their spelling, but as Taylor Swift proves, a typo can make an ordinary product seem extraordinary to fans and end up flying off the shelves. And if that happens, lyricists and publishers stand to make even more of a fortune. Assuming, of course, everything was properly licensed from the off.