As the genre continues to dominate music streaming consumption, will hip-hop catalogs become the next evergreens making the headlines? Music consultant Alaister Moughan investigates…

Catalog sales are rocketing but there are a few artists who are dominating the headlines. Boomer rock acts such as Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Fleetwood Mac and Paul Simon have made the biggest splash, prompting bidding wars as investors seek elusive ‘evergreen’ songs, aka the gifts that keep on giving.

An ‘evergreen’ record is one that is considered to be a standard part of popular culture, typically with decades of sales and ongoing radio play behind it. Yet, in a quickly evolving and growing music industry where publishing revenue breakdowns and trends of three years ago can seem outdated, will the songs regarded as ‘evergreen’ now really have the potential to remain standards?

Hip-hop dominates streaming listenership. It generates an estimated one third of all audio streams, which positions it as the standout growth genre of the industry. In its latest ‘Music in the Air’ report, Goldman Sachs estimates that 51% of catalog streams in 2020 came from songs made in the 2010s, an era which was dominated by hip-hop. In contrast, pre-1990 songs constituted only 12% of catalog streams.

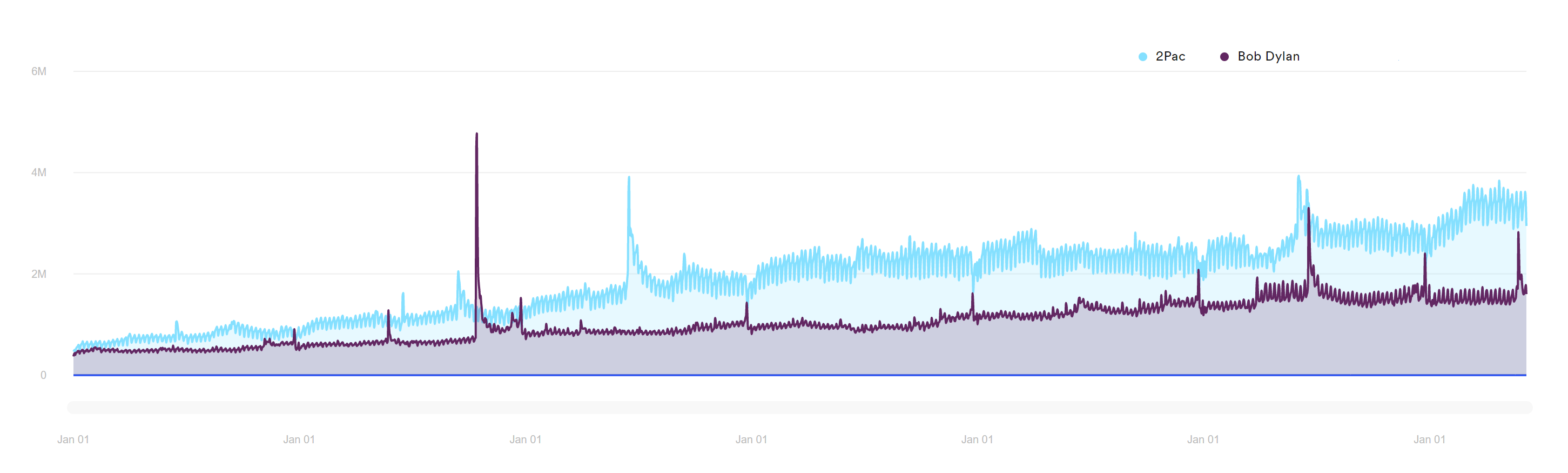

For some crude analysis it’s worth comparing Spotify’s daily streaming numbers from 2015-2021 for Bob Dylan vs. 2Pac (whose recorded music rights were recently sold via Hasbro’s sale of eOne Music). The opportunity is clear; Bob Dylan’s daily streams are tipping the two million mark while 2Pac’s are almost twice this.

It seems logical that hip-hop catalogs could become the next evergreens making the headlines. They are already being traded. Hipgnosis has acquired the catalogs of luminaries such as Pusha-T, No I.D., RZA and Timbaland. DJ Mustard sold to Kobalt, Tempo acquired Wiz Khalifa, and two of the biggest labels in the genre, Young Money and Death Row Records, have also been on the block. Just last week, iconic hip-hop label Tommy Boy traded hands for a reported $100m. This might be the start rather than end of the trend.

Dan Runcie, founder of the must-read ‘Trapital’ which examines the business of hip-hop, notes the track record behind boomer rock catalogs and historical scepticism of hip-hop as a potential hold back: “Classic rock albums have longevity. And I think the reason they have this longevity is because they’ve just been around for many more decades. When people see the continued success and the impact of something like a Dylan catalog, or a Dolly Parton catalog, it makes them that much more confident that it’s going to be like that for the next 50 years.”

“If you look at the influence and the impact of streaming, which in many ways is one of the main reasons why these catalogs are getting sold the way they are, hip-hop has been the backbone of streaming.”

– Dan Runcie, Trapital

In contrast, potential acquirers may have had questions around whether the hip-hop trend is going to last. Runcie thinks we have seen evidence that it is here to stay. “If you look at the influence and the impact of streaming, which in many ways is one of the main reasons why these catalogs are getting sold the way they are, hip-hop has been the backbone of streaming,” he adds.

Another factor which traditionally makes hip-hop catalogs more complex is the wider range of authors covering the lyricist, producer and various writers and rights holders of constituent samples. However, this is now a feature of most contemporary pop catalogs and is seen as less of a drawback.

Runcie also acknowledges external factors, such as low interest rates, which will drive sales of both classic rock catalogs and hip-hop catalogs, but cites a more apparent difference; age. Many hip-hop icons are still big frontline sellers and making major deals for new songs. Artists of this ilke have new monetisation avenues such as NFTs to explore in addition to a catalog sale.

It depends on the career stage of the creator: “If the RZA drops an album, that isn’t going to top the Billboard 200 just because he’s much more in that legacy phase. And because of that, it does make it more attractive to look at the alternative assets he owns and how he could maximize that.”

This is consistent with the view of high profile producer Tricky Stewart who sold his catalog to Hipgnosis. Speaking on the Musonomics podcast, Stewart explains that the decision to sell was influenced by his stage in life. He says the age of his catalog meant that he had collected the majority of the money from the hits he created and, as long as he got top dollar, he could do much more with the funds via his own investment portfolio.

This portfolio approach comes as no surprise as many of hip-hop’s biggest stars such as Nas, Jay-Z and Snoop Dogg are well known as being active savvy investors, providing case studies of astute ways to retain and expand wealth in diverse categories outside of music.

Guy Blake, Managing Partner of Granderson Des Rochers, who represent the likes of A$AP Rocky, J. Cole and Young Thug, has seen a significant change in demand for contemporary pop and rap catalogs which were ‘unsellable’ ten years ago.

“Sell because you have a plan for what you’re going to do with that money.”

– Guy Blake, Granderson Des Rochers

Different buyers have different appetites for contemporary catalogs. Behind the scenes, many of those doing the valuation “are more familiar with a Fleetwood Mac than they are with a Young Thug or Timbaland,” he says. So they stay within the safe space of this familiarity. As a recent Billboard article suggests, apart from the big names with pop crossover hits, hip-hop publishing catalogs trade at 10-12x NPS, an apparent discount from a market where 12x is the floor for catalogs of a meaningful size.

However, Blake thinks this safe space overlooks the demographic trends. Younger listeners who predominantly consume contemporary songs are the ones embracing new digital platforms. There are a growing number of music funds joining this view.

On the sell side, the conversation has changed significantly. Fifteen to twenty years ago there was a common distrust in corporate America and songwriters were focused on securing publishing administration deals with short retention periods.

In particular, due to historical horror stories, hip-hop artists have actively prompted and educated new artists on the importance of owning their own masters. This ownership itself is an outward show of pride and achievement for a number of artists.

More recently, however, the chatter around catalog sales, the sheer number and variety of creators selling, and the reported values being reached has changed the conversation significantly. Additionally, If an artist is able to sell their own master rights, the price they can charge will be considerably higher.

Blake’s clients tend to be very sophisticated in considering a sale, enlisting lawyers, business advisors, tax advisors and managers to determine if a sale is the right move.

According to Blake, a catalog sale must be part of an overall estate plan: “Sell because you have a plan for what you’re going to do with that money.” With sales of more contemporary artists, the meaning of ‘estate planning’ has evolved from inheritance to an artist’s long-term career roadmap.

Music attorney Robert Ross, who has more than 25 years experience in the business, recently joined me on a roundtable discussion on music assets for the Fixed Income Investor Network to discuss the importance of financial planning and legacy. He advised: “Remember, the music industry doesn’t have a 401(k). This [catalog] is the 401(k) that artists are dealing with now.”

If you are going to sell your 401(k) you should ensure you understand the implications.

“Remember, the music industry doesn’t have a 401(k). This [catalog] is the 401(k) that artists are dealing with now.”

– Robert Ross, R&R Entertainment LLC

“There’s this trajectory of learning, at least from an African-American and Latino or minority point of view. The songwriters have never been given the chance to own what they have created,” he explained. “For me, it’s personal. In my space, they just don’t understand. They have a number one hit and all of a sudden, they’re getting lowballed [but they don’t realize it because] they’re just not used to seeing this type of money. Their eyes open, for all the wrong reasons, they are prematurely selling instead of nurturing the asset or owning it in a fractional perspective and growing their businesses.“

Some artists can nurture these assets themselves. Ross points to Ronald Isley who is utilising his 60-year-old catalog by collaborating with musicians on TikTok and Instagram. Others can see the value of placing their legacy in the hands of someone who will curate and keep it intact.

As both Blake and Ross highlight, the catalog sale has become much more of an option to explore rather than a last resort. However, what hasn’t changed is the foundation of the value of an evergreen; its uniqueness. An author can only sell their evergreen once.

Enjoyed this article? Why not check out:

- Synchtank Summit Takeaways: Merck Mercuriadis on Rewriting the Rules of the Songs Business

- For What It’s Worth: Putting a Value on Music Publishing Catalogs

- 2020 x 20: The Themes That Defined a Blockbuster Year in Music Publishing Deals