We chat to Abi Leland, music supervisor and founder of Leland Music, about life in the sync industry, recent projects, and Christmas advertising.

Hi Abi, how did you first get started in the industry?

I started as a feature film music supervisor in 1998. I didn’t have a conventional route into it at all, I dropped out of school quite early and went to work as a runner at a film production company. My next job was at an independent dance label as their ‘office manager’. They specialised in compilations and would generally hire DJ’s to curate and compile them. As I was a drum and bass and dance fanatic, I ended up helping with this process and soon ended up compiling all of their drum and bass compilations, and also doing all the licencing for them. It was like my dream job at the time. I then moved on to a label called Simply Vinyl, who were in the niche market of re-releasing classic albums on heavyweight vinyl. They were releasing classic soundtracks like Easy Rider and scores by composers like Lalo Schifrin and John Barry, and it introduced me to the world of soundtracks and scores, which I hadn’t previously delved very deeply into. I started thinking, “I wonder who puts these soundtracks together”. So I asked around with my contacts in the film industry, and after many blank faces (this was 1997 when the role wasn’t as established) I eventually discovered that there was a job called ‘music supervisor’.

I was friends with the film composer Simon Boswell, who had started to work on Women Talking Dirty, the first film produced by Rocket Pictures, Elton John and David Furnish’s company. He asked me to come on board as the music supervisor so naturally I jumped at the chance. I’d already printed out business cards calling myself a music supervisor, so I really did bluff my way into it. I was wise enough to know that I couldn’t mess it up though, and that my experience with licensing for compilations would help but wouldn’t be enough. I was friends with my ex-business partner Dan Rose who was at the time working at the MCPS. I called him up and said, “do you want to come and do this film with me?” He left his job the next day and we started work in Elton John’s office. So that was my first project. We were very lucky – we landed film after film and it was just a great experience.

You set up Leland Music in 2005 and had some pretty major clients early on, how did those relationships come about?

I just plugged away at it really, as with anyone who starts up their own business. I had the good fortune to work on some brilliantly creative projects in the early days. I was a different set-up to the other music houses with their in-house studios and composers, so I was always reaching out to commercial writers and artists. That happens all the time now, but back then it definitely wasn’t common practice. With Hovis ‘Go On Lad’ I listened to a lot of Working For a Nuclear Free City, so I approached the band to write the score for it. The main writer, Phil Kay, had never scored to picture in his life, but he did a great job and now he’s one of the most sought after ad composers. I did the same with Sony ‘Foam City’ – the Nick Cave and Warren Ellis scores had a good feel for the film, so I went to Warren and he scored it. So I think I got a bit of a reputation for doing that sort of thing, which led to a lot of good projects.

The first song you pitched for the Lloyd’s TSB campaign was ‘Eliza’s Aria’, which is now so synonymous with the brand. Where did that come from?

I was introduced to the piece by Elena Kats Chernin’s publisher, Boosey & Hawkes. They had played me the song for a different ad, and obviously it’s a great piece of music, so I kept it aside for the right project. When Lloyds came along that was the first track that sprang to mind. We explored other options, but we did a full circle back to that piece of music and the animators worked closely with it.

You then started to work with adam&eveDDB on the John Lewis campaign, and they had already used a cover of a famous song in their 2009 Christmas ad. Is that where the idea came from?

The very first one, ‘Sweet Child O’ Mine’ by Taken by Trees, was an existing cover, so they used that without any pre-thought about it in terms of covers. The song worked and the cover version naturally worked much better to picture than the original. When I then worked on the next John Lewis ad there wasn’t any assumption that they would use or create a cover of a famous song, everyone approached the music with an open mind. It just naturally happened throughout the creative process. There I think because of the way the films are, they need something very simple. So, a lot of the time, creatively, it helps to use a cover.

Was it a conscious choice to continue using covers?

No, up until very recently everyone has always made a point of keeping an open mind and approaching each film with a fresh mind. In terms of finding the right song, it really is just driven creatively, and it’s about finding the right lyrics, the right tone, and there is an element of it needing to be from the right sort of artist/band. So whilst there is obviously now a formula, the music choice is always driven by the visuals and the narrative.

How early on do you start work on the John Lewis project?

We start once they’ve got a script. We’ll think about the music in a very explorative way, thinking about the lyrics and songs and the tone. That process is the longest part as they’re not going to commit to anything until there’s a picture, because it really is about how it connects with the film. We’ve been given a script in February before, I think that’s the earliest it’s been, and I fully embrace that. We see the film around August, which is always great because then we know we can really start to home in on it and decisions will be made. But for me the conception stage is the most fulfilling part of any project, when there is enough time to be explorative and inquisitive.

Speaking of Christmas advertising generally, what do you think is needed in terms of music?

I’m all about a good idea first and then responding to it, and there are no different rules for Christmas ads. The job of a music supervisor is essentially to tell the film’s story through music. We have to tap into the vision of the director or the creatives, so every project is different. I don’t think there’s any rules with Christmas ads, look at Coca-Cola and ‘Holidays are Coming’ – you only need to hear the first little bit of that music and you think, it’s Coca-Cola at Christmas. But is that what equates to successful Christmas ad music? Not necessarily. I really don’t think there’s any hard and fast rules.

What’s your favourite Christmas ad?

Ever? I don’t know! Ferrero Rocher! I’ll tell you my favourite one this year though, the Curry’s ad with Jeff Goldblum. It is brilliant and incredibly funny. I also think that the Mulberry Christmas ad is clever and funny.

How can you measure how successful a track in an advert has been?

With ads such as John Lewis we can measure it in terms of its commercial success, by its positioning in the charts and YouTube hits etc. But its success for the actual brand goes beyond that and is tricky to quantify as there are so many contributing factors to the success of an ad. There is now a lot of useful data that can be analysed by the industry so insight is possible. I’m hesitant to push this too much though as I don’t like it when creativity is driven by data. Success for me is all parties being happy, which is the hardest thing to achieve.

What are the most important elements in the relationship between you and your clients?

The thing that I never could have predicted would be the most challenging part of the job is to work with our clients collaboratively, and have a good communication stream throughout the project. With the people that we do have that relationship with, it’s obviously incredibly rewarding and the results show time and time again. But I find it sad and frustrating at times when the music isn’t approached with as much integrity as it could be. So that’s the biggest thing that I encourage – I want to work closely with our clients, and to know that we’re able to bring out expertise, knowledge, creativity, and integrity to the projects.

You’ve spoken before about issues in the relationship between agencies and the music industry. What are the main problems and how can we fix them?

Overall what’s going on is you’ve got two completely different industries coming together, which allows for much confusion and difficulty. As part of my job, I take it as a responsibility to effectively bring those two worlds together. There’s also been a shift in the music industry and a dropout in different areas, meaning that people have then gone into the world of sync. Because there’s no conventional way into it, there are no rules, which is great on the one hand, but also has it’s drawbacks. It’s become very messy, there are lots of blurred lines. People aren’t clearly defining what their role is within the market (half the time because they don’t even fully understand it themselves). The ad industry are then in a vulnerable position of lacking the knowledge needed to engage the right people, and end up having bad experiences with the music process, which taints their view of the music industry as a whole as well as specifically the sync part of it. Part of my job is to try and educate the ad industry and whoever we’re working closely with, to gain an understanding of music and sync and its value.

And to promote the role of a music supervisor.

Absolutely, the value of music and the value of the role of the music supervisor. I think that it’s constantly getting devalued by the way in which some people are operating within the music industry, which is incredibly frustrating because they shoot themselves in the foot, and with them the whole industry. But we have to just plug away and hope that enough people will play it the right way.

You’ve also spoken before about agencies pitching out to too many different music services.

In an ideal world I would prefer agencies to work on a project by project basis with one music supervision company, rather than having multiple companies and individuals competing throughout the entirety of a project. I think this is going to be a difficult thing to change because it’s so engrained in the culture of the way in which ad agencies work with music, and it’s too widely accepted. It’s also it’s possible for agencies to work this way because financially it’s not a big commitment for them. When you’re offering a music service, there’s a kneejerk reaction to keep lowering fees in order to be competitive. But again, that’s just going to keep feeding that way of working rather than encouraging the value of the music supervision service. I don’t anticipate it being something that will change overnight, but I do think it’s something that music supervisors need to encourage and keep questioning.

Moving back to the music supervision process, what are the most important considerations for you when you’re choosing music for a brand?

When you’ve got the script it’s really about having an incredibly open mind, and just having that stage to be explorative. I always try to get to the heart of the film and really try and work out what the feel is, what the tone is, what the message is. That can then be conveyed in different ways musically, but you need a thread throughout, and that’s what I try to stay in touch with when researching. When hiring music researchers, what I’m looking for is not necessarily someone with an encyclopaedic knowledge of music, it’s someone with an inquisitive mind. You need that when you’re working on a film. It’s having the instinct and the desire to experiment and ask questions, but with an empathy for the heart of the story.

It’s easier than ever nowadays to skip through an advert in the first few seconds. Do you think that music can be used as a tool to engage people more quickly?

Yeah, I do. How do you stop people from skipping to the next thing? Or how do you make an impact in just 10 seconds? I think music can massively help with that and it’s definitely something that more and more people are focusing on.

Can you tell us about some of your recent projects such as the Bulmers campaign?

Bulmers was a great project. The brand wanted to use music to help convey their message, which was about trying something new, and looking at the variety within their range. The creative team wanted to introduce something new to the consumer. Generally speaking, the Bulmers consumer is probably not au fait with grime music. So we were looking at grime and at bringing in different elements to work together to help convey the idea of variety. We had grime, we had orchestral, and we had soul, and that all came together. One of the successes of the campaign was that Lethal Bizzle, David Arnold and Sinead Hartnett just completely gelled. They didn’t want the project to end, so it was incredibly genuine.

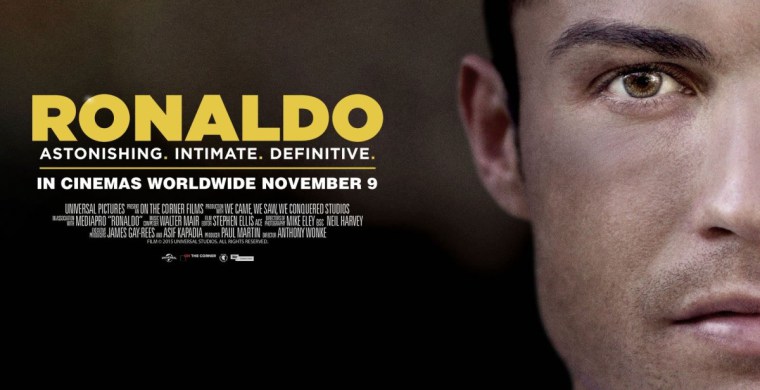

How did the Cristiano Ronaldo documentary project come about?

I knew the producers on it, so they approached me. I met them when they had a very loose edit, or really at that stage just rushes, to share. When I first heard about the project I wasn’t instantly interested in it. I’m not that into football, and I thought, Ronaldo’s a bit of a plonker isn’t he? But the moment I saw the rushes, I was hooked. It was shot interestingly, and I thought there was room to do something interesting with the score. We brought in Walter Mair, who’s a brilliant composer and the whole project was really enjoyable.

How do you think the sync industry is evolving?

I think that generally the lines are going to continue to blur and the culture of ‘content’ is going to grow, so this naturally affects music and sync. In terms of what we do, I think the fundamentals will remain the same. We’re just having to be adaptive in terms of the way in which the media is changing, and how content and film is exploited, and the way in which people are engaging with content and film. We have to make sure that we stay in tune with that and be innovative, but having good ideas and creativity at the center of it all.

Lastly, what was your reaction to Jimmy Iovine’s recent comments about women and music?

Well obviously it’s infuriating and depressing, and actually his comment was ridiculous and laugable. But in the end I felt a teensy bit sorry for him because we can all relate to saying something really stupid and then massively regretting it. But it’s good that he was at least pulled up on it, that it’s addressed, and that it encourages awareness and debate.