There is little doubt that the 2020 coronavirus pandemic is an unprecedented crisis on many levels. The number of infected cases and death toll continues to soar and we are yet to see the inevitable social and economic ramifications that could endure long after the pandemic passes.

People and businesses across the world are now trying to navigate the evolving situation. The music industry’s live sector has already experienced a huge shock to the system. We’ve seen job losses across leisure and hospitality as enforced social isolation cancels huge events like SXSW and Glastonbury. A large proportion of the music industry’s workforce are self-employed and are also in a precarious position.

Let’s not sugar coat this, it looks like it could be a rough ride for a lot of people and businesses. As bleak as it seems, this isn’t the first time an unprecedented socio-economic shock has rattled the world and it won’t be the last. Whilst the coronavirus pandemic is unlike anything we may have seen before, we will come out the other side as we have done with every other catastrophe.

To analyse how the music industry has reacted and survived in the past and how we can learn from this today, this article takes a deep dive into the major economic crises of the last 100 years and reveals the difficult decisions, effective leadership, and adoption of technology that helped the industry to bounce back.

Throughout the article, three prominent themes remain consistent:

- Courage and Compassion

- Innovative Leadership

- Rapid Adaptability

The Great Depression

1929 saw the end of the roaring 20s in an economically catastrophic global depression followed by a horrific world war. Unemployment rose to 25%, global trade collapsed, and after a year-long recession in 1949, the world finally began to recover in the 1950s.

As unemployment and striking became widespread, people stopped travelling for music. Live margins were decimated because many people came from out of town to see shows. Record sales were also hit as consumers turned to radio and film throughout the depression years.

When industries decline, one of the predominant forces is an increased intensity between existing rivals. This can naturally lead to consolidation amongst competitors. This is exactly what happened during the Great Depression with RCA acquiring the Victor Talking Company, establishing RCA records, and Columbia UK merging with the Gramophone Company, establishing EMI. The companies that were founded and survived the Great Depression became the foundations of today’s major labels.

In particular, a small Dutch record store would go on to become what is now Universal music. Decca’s Dutch imprint was one of the few label successes during the depression and continued to grow its sales even while the war raged across Europe. Towards the end of the war, it was acquired by Phillips. The complementary capabilities between innovative leadership in consumer electronics and creativity across the record label value chain allowed it to dominate the 20th century as PolyGram and eventually Universal.

Lessons for Today

Despite the nascent state of the music industry during the Great Depression, there are two points that ring true today. First, the interconnectedness of the live and recorded sectors shouldn’t be understated. We all feel the consequences when one suffers. Also, music was substituted even when the only other options were radio and cinema. With today’s video games, SVOD platforms and social media, it’s no surprise that music streaming is starting to suffer.

The aftermath of the Great Depression saw the integration of the music industry with consumer electronics. As we will continue to see, exceptional management and leadership from the tech sector have been more than beneficial for the music industry in a crisis. The music industry needs innovative leadership to guide it through times like these.

If you can adapt to succeed in the worst of times, you can thrive when things get better and easier.

The economic decline so far has been unsettling and its potential to get worse makes it even more so. Business is about to get a lot more competitive. Some companies may go bankrupt and jobs are already being lost. Those that endure may emerge with lessons that will serve them for decades. If you can adapt to succeed in the worst of times, you can thrive when things get better and easier.

1979 Oil Crisis

The good years after the Great Depression led to the music industry’s longest period of sustained growth. However, in 1979, the Iranian revolution led to a global oil crisis that played a big part in the following early 80s recession. The cost of oil skyrocketed, having implications for the price of pretty much everything else

Live music suffered again, this time more acutely outside the US. The crisis led to a rally on the dollar and suddenly the cost of booking American artists skyrocketed. One example saw a European promoter go under when the new exchange rate increased booking fees by $100,000. Travelling also became much more expensive, reducing leisure spending that some assumed would lead consumers to buy more records and sit at home to listen to music. However, a declining economy and overconfidence don’t seem to mix well.

The music industry had been growing so well that leaders were expecting the growth to continue. Record companies overextended themselves and were pressing much more than they could sell as demand dropped. The result for Polygram, in particular, was daily losses of $300,000, which led to losses of $200 million in the early 80s. There were multiple attempts to consolidate but a merger with Warner was blocked by the Federal Trade Commission.

Leadership from Phillips was brought in to steady the ship. Massive downsizing and cost-cutting led to big job losses but the successful introduction of the CD helped lead to a rapid turnaround. By the end of the 80s, Polygram would be worth over $2 billion and increase more than fivefold over the following decade.

Lessons for Today

Again, the live music sector was an early casualty and subsequently demand for recorded music dropped. The crisis saw more people socialising at home, though this was due to the expense of going out rather than a health pandemic. The dollar also rallied like it is today so we may see this impact on international touring.

No one wants to think about how bad things can get when they are going so well. The World Bank’s 2013 pandemic report captured this quite effectively:

“Leaders in private and official circles may ignore pandemic risks, because they consider that nothing will (probably) happen on their watch, that alarming approaches will make them unpopular, and that tackling existing, visible, problems will provide greater exposure and better prospects.”

The same can be said when addressing risk in any industry. Unfortunately, this pandemic is likely going to be one of the most expensive lessons in risk management the world will ever experience. Whilst we could never control something unprecedented like this, our world is so interconnected that we must never assume we won’t be affected by an impending crisis.

Now more than ever is a time to address the biggest risks and threats that face your organisation and industry.

Now more than ever is a time to address the biggest risks and threats that face your organisation and industry. The example of PolyGram’s quick turnaround came from quickly grasping the situation, establishing the right priorities and making decisions that bring about change. It started with cost-cutting but it was boosted by many other clear and effective decisions that put it in a position to innovate and succeed.

Black Monday 1987

After stabilising from the early 80s recession, stock markets across the world experienced a sudden and dramatic crash in October 1987. Over a few days, the world stock markets had lost around a quarter of their value.

This unexpected and immediate financial crisis had instant implications for the music industry throughout the world. The biggest consequence was the sale of CBS, then the world’s largest record label, to Sony. This was a symbolic move for a couple of reasons. It was the first Japanese acquisition of a major US company. Unlike other crises that put the brakes on global trade, this crisis helped facilitate it.

Phillips and Polygram’s accelerating growth showed the value in connecting consumer electronics with the record industry. Sony had just developed digital audio tape and, like Philips with the CD, were now able to more effectively integrate it across the music industry.

The entry of Sony amidst a sudden crash now made rivalry amongst record labels as intense as ever. The response changed independent music forever with a run of major acquisitions of indie labels to increase market share, including Island, A&M, Motown and Virgin. After spending over a billion dollars on acquisitions, PolyGram announced an IPO for 20% of their shares in 1989. This was initially announced days before Black Monday but was inevitably put on hold after the ensuing market volatility.

Lessons for Today

As this crisis unfolds, there may be more opportunities for rising global powers to emerge as more dominant forces in the music industry and the broader global economy. Learning from their previous experience dealing with the SARS outbreak, countries in East Asia seem to be navigating this crisis far better than many countries in the West. Because of this, they may very well come out of the pandemic quicker and in better economic health.

The birth of Sony as a major record label was a sign of Japan’s increasing prominence on the international stage. The easiest comparison to make today is Tencent and their recent and significant investments in the music industry.

The birth of Sony as a major record label was a sign of Japan’s increasing prominence on the international stage. The easiest comparison to make today is Tencent and their recent and significant investments in the music industry. The recent rise of China is unlikely to slow down after this crisis and the emerging landscape may be favourable for more international players to establish powerful positions.

PolyGram’s delayed IPO offers eerie parallels with Warner Music Group, who have just put their planned IPO on hold. After two years of growth and over a billion dollars of independent acquisitions, PolyGram found a new window for it’s IPO with its new valuation increasing by $290 million compared to 1987. It remains to be seen how long it takes for Warner to come back to the stock market, what it does within that time and how much its value will be affected.

1997 East Asian Financial Crisis

In 1997, Thailand’s currency crashed and eventually collapsed, triggering similar situations in neighbouring Asian countries. As South Korea’s currency was crashing, record sales fell by 54%. The Asian crisis also rippled across the world, most notably in Latin America where Brazil and its music industry suffered significantly as record sales nosedived by 41%.

The crisis laid the foundations of rapid economic transformation in South Korea, centred around the cultural and creative industries. The government heavily invested in digital policies and infrastructure. The vision was to become the first music industry to have higher digital revenues than physical. Coming out of this crisis would require a collective effort from the creative and tech industries alongside the public sector.

After the financial crisis, South Korea’s mobile telecom giants Samsung and LG gradually became global forces. Domestically, they were part of a larger ecosystem that oversaw the earliest adoptions of mobile music consumption. Despite what can be considered as looser copyright protections, industry business models saw quick innovation by focusing on the service first and copyright permissions later. This led to South Korea’s idol industry being as focused on B2B sales with the advertising industry as it was on consumers.

By the end of the next decade, South Korea had transformed and miraculously rebounded from the crippling financial crisis. South Korea’s leading record label, SM Entertainment showed what this looked like in the music industry. In 2011, the majority of their royalties came from abroad – this was the price of putting domestic copyright on the backseat. However, about a third of its revenue came from service sales based on the B2B model.

Lessons for Today

As South Korea shows, economies and industries can still bounce back even after they’ve been hammered by an economic crisis. The coordination between the cultural industries, the government and tech companies shows how societies can collectively respond in a crisis. The effects of today’s pandemic first and foremost need to be dealt with by governments as an international health crisis. From there, collaboration across society is needed to come back even stronger.

In hindsight, the vision of the South Korean music industry was way ahead of anywhere else in the world following this crisis. Even then they knew the only way forward was digital. Strategising the future economic well being of a nation on the back of the entertainment industry was a brave and radical move to say the least. Despite rampant piracy, innovative solutions were found. South Korea’s music and advertising industry became increasingly intertwined, arguably foreshadowing the growing influencer market we see today.

Unity between governments, culture and tech could pave the way for a rapid rebound and a prosperous future.

An economy won’t simply get better by itself. Pretending nothing happened isn’t going to do much good either. A global crisis changes the world on many levels and this is going to be no different. We can’t control what’s happening but we can control how we respond. Unity between governments, culture and tech could pave the way for a rapid rebound and a prosperous future.

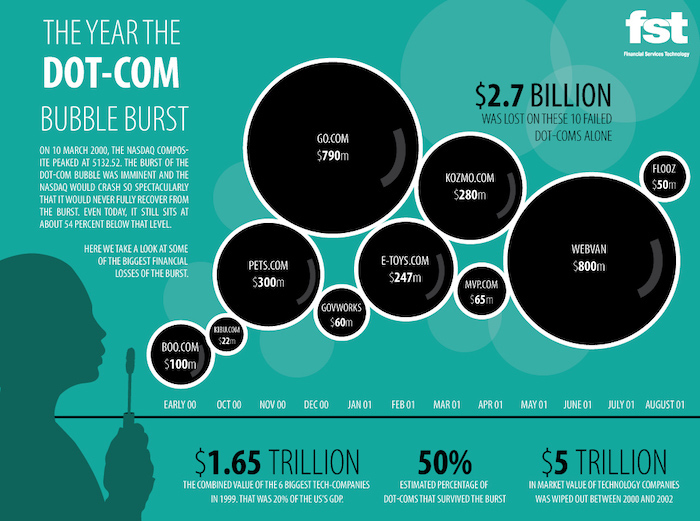

The Dot Com Bubble

The rise of the internet resulted in an astronomical rise in the value of startups. However, this overinflated value dramatically collapsed as the bubble burst after their profitability came under increased scrutiny.

At one point, an online music company called CDNow attracted more buyers than Amazon and was one of the most popular eCommerce companies. Its fall was as rapid as its rise as it collapsed after the bubble burst. More importantly, this period also saw the rise of file sharing sites that saw piracy explode. Business models were under severe threat and the value of the music industry dropped like never before over the next decade. The declining consumer demand in the challenging economic climate was bad enough. The failure to adapt to the internet made things so much worse.

Major labels lost roughly a third of their workforce and roster as the industry declined over the 00s. One high profile example in 2002 saw EMI pay $28 million to end Mariah Carey’s record deal only a year after signing it. Joint ventures with artists were also shut down and private funding for music startups became scarce.

The unbundling of albums through digital retailers led a shift towards a singles market. This was driven by innovations that came from outside the music industry, such as through Apple’s iTunes and iPod. The CD and cassette tape helped weather storms for Polygram and Sony in the past. Now the music industry was left at the mercy of technology.

Lessons for Today

The bursting of the dot com bubble wasn’t a global crisis in the same sense as the other examples here. It may have been rough for a lot of startups but the survivors, such as Amazon and Google, are now amongst the most successful companies in the world. Fighting the technological innovation that underpinned many of these companies created a crisis for the music industry. Simply embracing it could have created huge opportunities.

This was the music industry’s most significant failure to control the innovations that would define consumption. Artists and workers were the biggest victims. However, although there was little margin for error, this was a great time to be a superstar artist or executive. If you can sell records at a time when no one’s buying them then your bargaining power skyrockets.

There has gradually been a shift to a more startup-friendly music industry. We can see this in the innovation investment and startup accelerators across the major labels.

The lack of private funding and need to quickly innovate led to the birth of labels as venture capitalists. Although the eventual launch of Vevo from Universal wasn’t enough to turn the tide, there has gradually been a shift to a more startup-friendly music industry. We can see this in the innovation investment and startup accelerators across the major labels. Technology is going to continue to change and disrupt the world. Let’s hope the music industry won’t fight it.

September 11 Terrorist Attacks

The 2001 terrorist attack on September 11th had a devastating impact with thousands of lives lost and, in some cases, killing the majority of the workforce of entire companies. This was a psychologically traumatic catastrophe that no one could have anticipated and was a crisis of humanity first and foremost.

The following days rattled the world economy and temporarily shut down stock markets. Airlines were grounded immediately which led to one of the first significant effects on the music industry. Major tours from the likes of Madonna, Janet Jackson and U2 were either cancelled or indefinitely put on hold. The insurance industry also suffered intensely and needed to take action to remove risk from their portfolio. Live music was considered high risk and touring insurance either vanished or was offered at massively increased prices. Furthermore, terrorism began to be excluded from policies as a result of the attacks.

None of this looked good for the live sector at the time. However, this was the start of a new era of unprecedented growth for live music. Things started to normalise in 2002 and the sector would consistently grow, doubling in size over the next 6 years until the 2008 recession.

The RIAA came under criticism for trying to capitalise on the crisis. They attempted to insert an amendment in the Anti-Terrorism bill that would essentially allow them to hack the computers of suspected pirates. Poor taste was one way used to describe this opportunism. More than anything, it was a sign of the desperate lengths the industry was prepared to go to to fight the technology it couldn’t control.

Lessons for Today

The initial aftermath of the 9/11 attacks shares a couple of distinctive similarities with the current situation we face today. First is the grounding of flights and the cancellation of live music. Second, the insurance industry is likely to be put through the wringer again, especially given the duration and global nature of this crisis.

If there is any cause for optimism, it’s the rebound of the live music industry in the following years. Unlike previous economic crashes, the aftermath of 9/11 wasn’t a result of financial mismanagement. Demand was put on hold temporarily and bounced back big time. There’s no guarantee that will happen again but given the health of the industry before this crisis, live music shouldn’t be written off as a long term casualty.

In times like these, businesses will be at their best serving society when it needs it most. If there’s ever a moment for courage and compassion it’s during a crisis like this.

The trauma of 9/11 was real and it was a horrendous shock for society. In times like these, businesses will be at their best serving society when it needs it most. If there’s ever a moment for courage and compassion it’s during a crisis like this and remember, how you communicate is just as important as what you’re communicating.

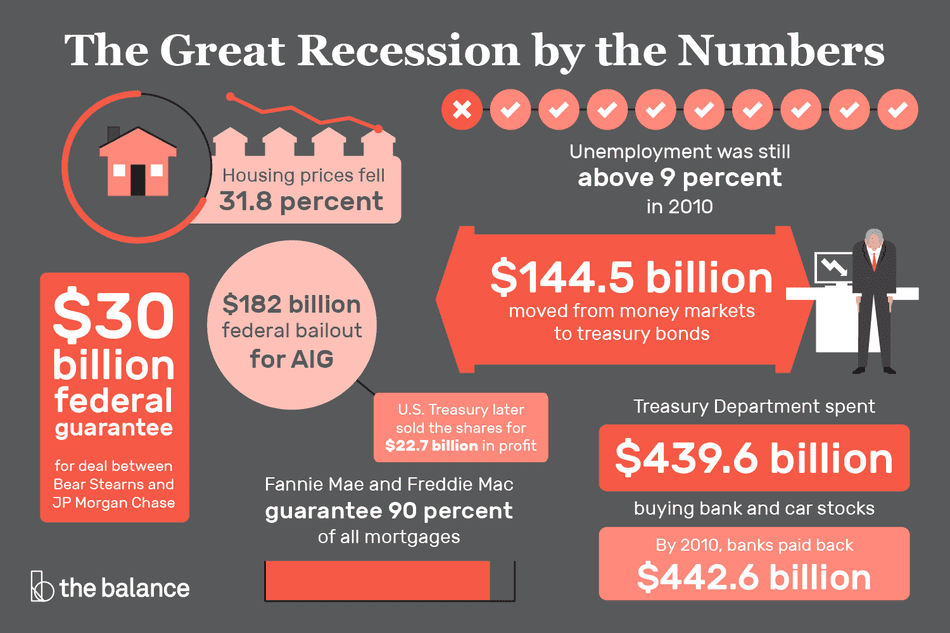

The Great Recession

2007 saw the beginning of the most severe global financial crisis since the Great Depression. Radical financial responses across the world tried to protect jobs as much as possible. Unemployment was kept relatively low in the aftermath for a crisis of this magnitude. The trade-off was in wages, productivity and job stability.

As we’ve seen time and time again, live music took the first hit. The weak dollar meant that this was felt harder in the US, leading to festival cancellations and a 26% drop in ticket sales in 2010. During this time, other countries, such as Australia, continued to see live growth. Although the market was hard for new entrants, many established festivals also continued to sell out and the global industry returned to growth in 2011.

The Great Recession saw technology and the music industry come together after years of resistance. First was the launch of Spotify which would usher in the new era of streaming over the next decade. The second was Live Nation’s merger with Ticketmaster. Like the rest of the industry, Live Nation was prepared to go to war against the technology that was threatening it. However, it saw that joining forces with it was easier and inevitably reaped the rewards.

This crisis also unveiled a growing opportunity to find new revenue streams to offset the record industry’s decline. Sync was a big part of this for publishers. Like the Great Depression, the recession couldn’t hold back the film industry. However, it was the video game industry that demonstrated its resilience in an economic crisis. Remarkable growth from some of the biggest successes at the time included Grand Theft Auto, Fifa and Guitar Hero, all of which prominently feature music.

Lessons for Today

As seen in previous crises, live music was hit immediately but rebounded within a few years. However, this crisis really drove home the performance and dominance of the video game industry. Even today in a pandemic, gaming is one of the most effective remedies for social isolation. There’s a reason why Netflix identified Fortnite as its biggest threat. For any form of media and entertainment, it seems that gaming may be the ultimate substitution.

The establishment of Live Nation Entertainment as the most dominant force in live music demonstrates the power of working with technology instead of against it. Dominant positions like this are hard to come by in any industry. For a sector that always seems to immediately suffer in a crisis, maybe a corporation with the capacity to absorb shocks is exactly what live music needs.

As new behaviours emerge in a crisis, so do opportunities to generate new sources of revenue for artists, publishers and collection societies.

The growth of the sync industry has been great for music and it took years of decline for the industry to really start exploiting its potential. Who knows how many revenue streams are yet to be discovered. For example, live-streamed performances are taking off amidst social isolation. As new behaviours emerge in a crisis, so do opportunities to generate new sources of revenue for artists, publishers and collection societies.

Tōhoku Earthquake & Tsunami

In the aftermath of the Great Recession, Japan suffered one of the most powerful earthquakes ever recorded. This triggered a tsunami that killed over 15,000 people and created the worst nuclear disaster since Chernobyl at the Fukushima nuclear power plant.

The Japanese market crashed as the country dealt with the fallout of what would become the most expensive natural disaster in history, costing the country hundreds of billions of dollars. The devastation from the earthquake and tsunami was bad enough. The fallout from Fukushima meant that this had become a severely alarming health crisis.

Many international tours were cancelled and in a show of collective mourning, the Japanese engaged in what is known as jishuku, or self-restraint. This effectively led to social isolation and large numbers who had to work from home. In some cases, this was necessary to avoid the nuclear health hazard.

Music is a great unifier of people when times are rough. This truly devastating crisis showed how quickly the world and the global music industry can coordinate to support those in need. Majors and independents across the world found ways to support Japan and despite the horrendous impact of the disaster, Japan’s music industry actually grew the following year.

Lessons for Today

The Tōhoku Earthquake and subsequent disaster seems to offer many similarities to our present-day situation. The first is that a similar or even worse death toll and economic impact may be seen across multiple countries. Secondly, there is a distinct parallel regarding social isolation in response to a serious health hazard. Like today, a public health crisis was seen to be more of an issue for older generations and the young were much more eager to emerge from social isolation. The third is the shutdown of the live industry. Whilst a financial crisis primarily affects demand and spending, disasters like Tōhoku, 9/11 and today’s pandemic have profound effects on humanity that require significant and immediate social changes.

Finally, as the crisis came and went, the solidarity and outpouring of compassion from the world helped make things better. Organisations, industries and governments came together and put differences aside to support those suffering the most and it can happen again. Despite the unprecedented scale of an earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster, Japan’s economy returned to growth after 6 months. A pandemic may be a vastly different crisis to this but we should never underestimate the human resolve to bounce back.

Despite the unprecedented scale of an earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster, Japan’s economy returned to growth after 6 months. A pandemic may be a vastly different crisis to this but we should never underestimate the human resolve to bounce back.

The Japanese have an expression, ‘itami wake’, meaning to share the pain. You can see this in many Japanese companies, who are far more reluctant to fire employees when times are rough. This is because their cultural attitude is centred around the collective responsibility to share losses together. As the world goes into lockdown and suffers from this pandemic, perhaps we can all find inspiration from an attitude of collective responsibility.

Final Thoughts

A 1949 issue of Billboard in the depths of the post-war recession featured what it described as an old record industry fable, which I’ve summarised for us all to enjoy:

A hot dog salesman had a booming business with no idea of the chaos going on in the world around him. One day his college-educated sons told him that there was a horrendous global depression. They said he needed to cut his costs on supplies, advertising and promotion, so he did. His orders fell almost instantly. He realised his sons were right, there really was a depression going on.

Whilst none of us here endured the worst of the Great Depression, the staff at Billboard at the time surely had some idea what it was like. I’ve adapted their lessons from the fable below. Although this was written over 70 years ago, I felt that these lessons were well worth including to help remind us of some fundamentals for a successful business in challenging times.

A good product makes a good market: When a great artist, song and production comes together, nothing can stop people from paying for music.

Consistent, intelligent promotion pays off: Know what your customer wants and use your imagination to find ways to keep communicating with them.

A little knowledge is a dangerous thing: When there’s a crisis, people are determined to find it. If things are still working, don’t try and fix it.

Your business is what you make it: When times are rough, your mindset needs to focus on adapting to change. It may feel like riding a meteorite, but it’s sure better than getting hit by it.

11 comments

Thank you for such a fantastic historical account of how the music industry will always bounce back! This was a great article.

Fantastic article, Kriss. Smashing!

[…] update 5: And here are some crisis management lessons you might want to […]

[…] great depression and see patterns that are very likely to repeat themselves. Thinktank Synchtank analyzed the music industry during the late ’20s and early ’30s and saw concerning trends. […]

[…] great depression and see patterns that are very likely to repeat themselves. Thinktank Synchtank analyzed the music industry during the late ’20s and early ’30s and saw concerning trends. […]

[…] https://www.synchtank.com/blog/crisis-management-lessons-from-the-music-industry/ […]

[…] Com informações de: Folha de S.Paulo, Yonhap News, Forbes, OkayPlayer, Synchtank, […]

[…] Com informações de: Folha de S.Paulo, Yonhap News, Forbes, OkayPlayer, Synchtank, […]

[…] impact economic mondial al coronavirusului nu a fost încă văzut, dar rapoartele timpurii sugerează că ne-am putea îndrepta către ceva comparabil cu cel al marii depresii, […]

[…] impact economic mondial al coronavirusului nu a fost încă văzut, dar rapoartele timpurii sugerează că ne-am putea îndrepta către ceva comparabil cu cel al marii depresii, […]

[…] impact economic mondial al coronavirusului nu a fost încă văzut, dar rapoartele timpurii sugerează că ne-am putea îndrepta către ceva comparabil cu cel al marii depresii, […]