It might seem like an unlikely sector of the market for an EDM star – more used to Las Vegas residencies or performing within Fortnite – to move into, but the fact that Marshmello has created a kids’ brand says a lot about where the music market is today and even more about where the audiences of tomorrow will come from.

Created by Marshmello and his manager Moe Shalizi, MelloDees is a YouTube channel aimed at preschoolers where the DJ gives well-known nursery rhymes a “hands-in-the-air” rave remix. It sees animated character Dee scamper around a brightly coloured world as tracks like ‘ABC Song’ and ‘Rock-A-Bye Baby’ play (others like ‘Wheels On The Bus’ and ‘Itsy Bitsy Spider’ will follow). The songs and animation lean heavily on repetition to drive repeat plays on YouTube as well as earworm their way into an extended life on Apple Music and Spotify.

“Children’s screen time is at an all-time high,” Shalizi told Rolling Stone, adding that he and Marshmello were looking to “fill a gap in children’s programming”. They are trading in classic nursery songs that come with the added benefit of being in the public domain.

Does this nursery-centric branding mean an automatic loss of credibility for someone who has previously courted a more grown-up audience who flail around on slightly different types of E-numbers? If recording nursery rhymes and lullabies – which is what ‘Yellow Submarine’, ‘Octopus’s Garden’ and ‘Good Night’ effectively are – were good enough for The Beatles, then they are good enough for the acts of today. Plus credibility concerns can be quietly parked when this is a boom market and set to grow even further.

This trend, of course, did not come out of nowhere and companies have been investing in this area and buying up content and rights long before the megastars of electronic music showed an interest.

Alice Dyson-Jones is MD of One Media and says this has been a key investment area for the company for many years.

“Kids’ [music] has always done well for us,” she says. “It’s one of our strongest catalogues.” Key to that has been its partnership with Songs For Children, a company which started in the late 1970s making original recordings of public domain classic nursery rhymes as well as counting songs and stories.

“Kids’ [music] has always done well for us. It’s one of our strongest catalogues.”

– Alice Dyson-Jones, One Media

The name Songs For Children may seen generic but that has proven to be its greatest strength in an age of SEO – particularly voice-activated search.

“If you think about search, when you’re asking Alexa or any of the digital stores for kids content, you say, ‘I’m looking for songs for children,’” she explains. “When your label is called Songs For Children, that’s really helpful.”

She says that One Media has been operational for 15 years and as such “we were only ever a digital business”. That has meant that the metadata around its kids’ catalogue has been watertight and is really coming into its own now, especially on its Kids’ Clubhouse YouTube channel.

“We put in all kinds of search terms, we did series compilations – One Hundred Lullabies, 50 Kids Car Songs – and we thought very early on about how parents search for children’s content,” she says, “because for this demographic it’s the parents that are searching, not the kids.”

Edwin Cox is CEO of West One Music Group and his company has recently partnered with Lego’s Duplo brand (for children up to the age of 5) to release a series of songs and animated videos for young children to help with their education and development. They are a mix of well-known songs as well as new compositions that are structured around three themes – Happy Birthday, Lullaby Songs and Nursery Rhymes.

“All major kids’ brands use music, alongside other media, as a key part of their strategy – as a way of enabling their educational and brand focus to be brought to life in a fun and engaging way,” he says of the deal with Lego Duplo. “We also know from a developmental perspective that music helps the body and mind work together to ignite all areas of child development and social skills, including intellectual, social-emotional, motor, language and overall literacy. Exposing children to music during early development helps them learn the sounds and meanings of words, along with supporting skills such as spatial awareness, working memory, listening and early maths.”

“All major kids’ brands use music, alongside other media, as a key part of their strategy – as a way of enabling their educational and brand focus to be brought to life in a fun and engaging way.”

– Edwin Cox, West One Music Group

He says the meshing of music and visuals is critical for children and, as such, the company has been building and refining its YouTube strategy over the past three years. “We are currently working side by side to develop a repertoire of original music and video content for a global audience,” he says of the Lego Duplo partnership.

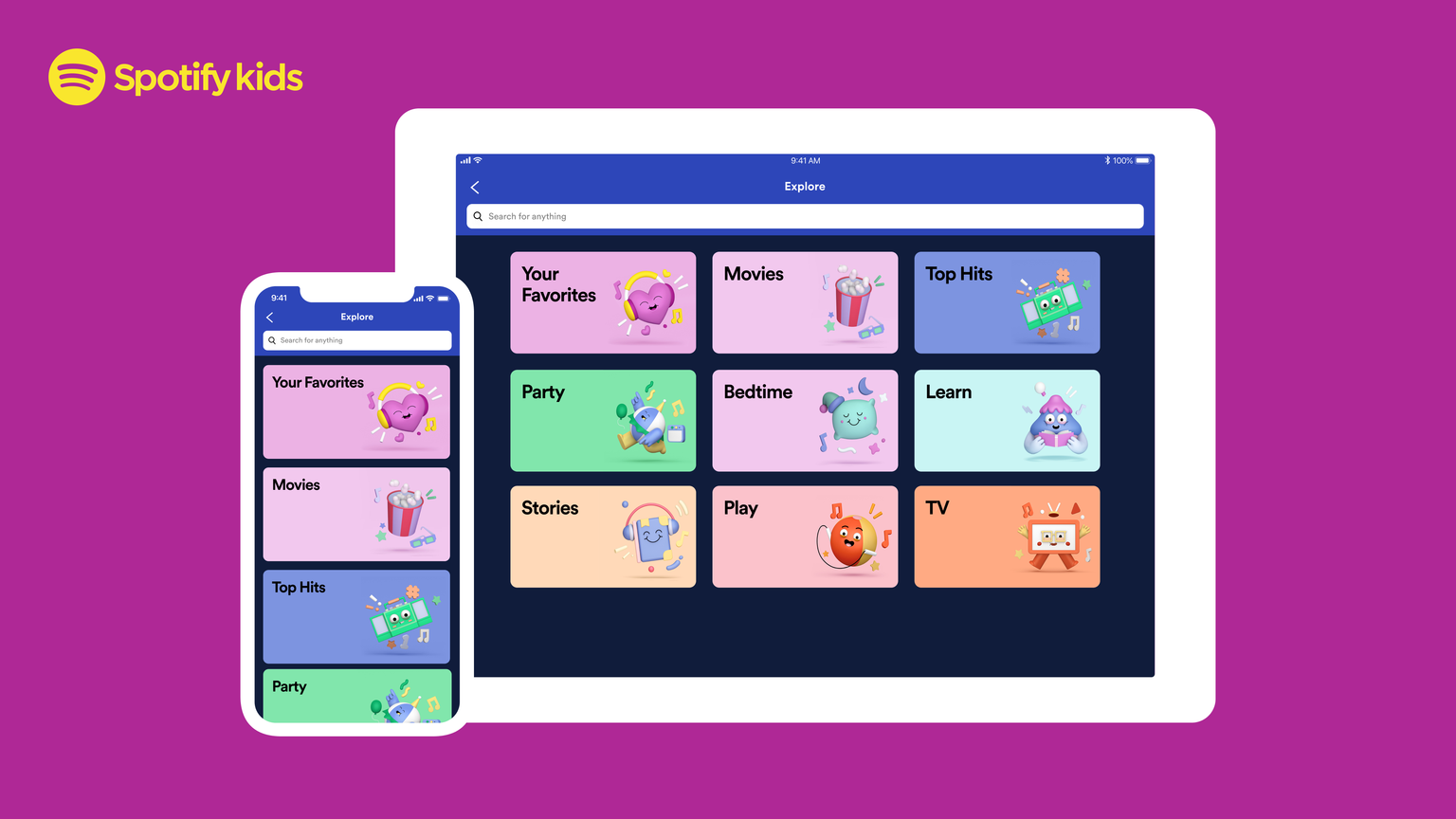

While YouTube has been a critical platform for kids’ content – aided enormously by the launch of the YouTube Kids app in 2015 to ensure only age-appropriate content is served up to its young audience – the audio-only services are also growing in importance. Spotify Kids started rolling out globally last year as a standalone app as part of a family subscription. It is there to ensure explicit content cannot be accessed and to ring fence parents’ listening so that the algorithms powering their Discovery Weekly and Release Radar playlists are not flooded with nursery rhymes.

Spotify Kids has 8,000+ songs and stories that are screened for suitability for a young audience and it was developed with the intended listener base in mind rather than their parents. “There’s audio everywhere and kids can’t get enough,” Alex Norström, chief premium business officer at Spotify, told Billboard in May. “But all of these audio experiences were built with adults in mind, which means they are not easy for kids to navigate, they’re not very much fun to use, and they aren’t traditionally designed for impressionable young minds.”

It is the playlisting aspect on DSPs that is critical here for the future of kids’ music online. One Media has its TCAT system for optimising content (as well as protecting rights) online and this gives it insights into where music is best performing on digital services.

“We’re able to identify playlists that have traction and playlists that perform well – and how tracks are seeded,” says Dyson-Jones. “We have all this insight into the lifecycle of a playlist. We use that information to help us prime the content we put together.”

Cox suggests that this is obviously important for the future of the sector but that it is currently at the nascent stage.

“It’s still very much early days with the DSPs and especially Spotify and Amazon,” he says. “They have only recently rolled out their children-focused areas, so at this stage there isn’t a huge amount of potential on the playlist side. But it’s clear this will change and evolve imminently. Some of the other major players are only just in the learning phase.”

He points out that YouTube is, however, much more advanced than the audio services presently. “In comparison, YouTube has had a kid’s app for years now which is very simple and very interactive, whilst also serving voice recognition,” he says. “It’s a totally different interface and one that is clearly intuitive for the kid’s audience. YouTube is definitely one step ahead due to their dedicated interface for children – we have yet to see this play out in full with the music players.”

“YouTube is definitely one step ahead due to their dedicated interface for children – we have yet to see this play out in full with the music players.”

– Edwin Cox, West One Music Group

The major music companies – swift to capitalise on a growing trend – have already charged in here, linking with a flurry of established brands in the kids’ market in recent years.

Sony Music UK launched the Magic Star label in October 2019 to focus on “children’s audio and audiovisual content – from pop music and spoken word to live events for the whole family to share”. It signed up Oscar, an animated character developed by Smyths Toys, in July to increase its footprint in the space.

Universal, meanwhile, entered an exclusive partnership with Lego in April to work on “a new suite” of Lego products for 2021 “that will enable children around the world to explore their creativity through play, by expressing themselves through music”.

Olivier Robert-Murphy, global head of new business at UMG, said of the deal, “Music plays an integral part in every child’s life from the moment they are born and throughout their development. Across the decades, children have continued to explore this passion via vinyl, radio, cassette, music videos, CDs and streaming. Now through the partnership between the Lego Group and UMG, we will provide a new interactive way of inspiring the next generation of fans and creative visionaries.”

Warner Music, however, has been leading the pack in terms of what the majors are doing here. In 2018, its Arts Music division partnered with Sesame Workshop, the non-profit education organisation behind Sesame Street, to relaunch Sesame Street Records in North America, bringing its catalogue to streaming services and working on new compilations and new music.

Then in July 2019, its recorded and publishing arms signed up with Build-A-Bear Workshop to launch the new Build-A-Bear Records label. It also sits within Arts Music and is focused on releasing new albums and singles as well as developing playlist brands.

And in May this year, Warner signed a global music licensing agreement with Mattel (the powerhouse behind Barbie, Thomas & Friends and Fisher-Price), to be the sole distributor of its catalogue of 1,000+ songs – including music that has never been released before.

Dyson-Jones is not so concerned about the majors attempting to aggressively buy their way into the market in this way. “There’s opportunities for everyone,” she says of the market’s ability to support an influx of new players.

She is less critical of why the majors have moved in here but more critical of how they have done it.

“It’s not very creative,” she says of the deals they have signed with existing names in the sector. “You’re putting music into brands that are well-established. So you’re going route one, which is typical of the majors to take something that’s already developed and then get involved. If you think about the role of the independent sector, their job is to nurture creativity, look for the niches, be disruptive, nurture the green shoots of talent.”

She feels the indies will remain the originators and the pathfinders here. “The height of creativity, in my opinion, comes out of the independent sector,” she argues. “And will continue to do so. That’s why they have to continue to coexist. They have this awesome pool of new talent and ideas. They have to work a bit harder to make it work.”

“The height of creativity, in my opinion, comes out of the independent sector, and will continue to do so.”

– Alice Dyson-Jones, One Media

Cox is more sanguine. “For us this is not about the size of the company or catalogue, it is about creating meaningful and engaging songs – which, outside of the traditional nursery rhymes, provide our audience with something that is completely new and original,” he says.

He adds, “Surprisingly, the biggest players currently online are often smaller independents and not the likes of Disney and Pixar.”

The impact of lockdown has been bittersweet for kids’ music as it has seen a significant growth as young children of working parents were having to be kept at home and entertained rather than being sent to nursery or school.

Dyson-Jones says recent data she has seen as an indie label representative on the BPI Council makes it clear that consumption of child-centric content has spiked during lockdown. “There’s been an increase in consumption of kids’ content, classical content and ambient music,” she says of the shifting listening trends here. “The commute has stopped and also the gym has stopped. The kinds of content consumed in the gym and on the commute is definitely not kids’ content!”

A report in USA Today in the early stages of lockdown provides some numbers here. Amid falling albums sales and the total implosion of live music, it was children’s music that saw a growth spurt. “Since schools suspended classes, children stuck at home have been busy streaming on all their devices,” it reported in April. “Streams jumped 12% week over week. Children’s audio streams were up 5%, while video streams soared 22%.”

Sasha Junk, president of Kidz Bop, says her company has experienced a massive uptick in consumption here. “We’ve seen a big increase in views and streaming,” she told Kidscreen. “On YouTube, our views were up 32% in the first few weeks of the pandemic, and children’s music streaming in general was also up.”

Dyson-Jones feels that this could be the start of a significant and abiding change rather than a historical blip.

“The habits that we are having established now – for the period of time that we’ve been in this lockdown – is sufficient for permanent behaviour changes to take place, in my opinion,” she says. “If it had been a month, everything would have gone back to the way it was […] Consumption from home is only a positive thing for us. The future for music is rosy in my opinion.”

“The habits that we are having established now – for the period of time that we’ve been in this lockdown – is sufficient for permanent behaviour changes to take place.”

– Alice Dyson-Jones, One Media

For Cox, the markets that are being opened up globally by streaming platforms will have a significant impact on the types of content being created here.

“Localisation of content is huge in this arena and is an absolute must,” he proposes. “Lego Duplo has a very global marketplace and delivering local content to audiences around the world is a key focus. By example, we have created and produced all our music with Lego Duplo in Russian, Korean, French, German, Polish and Chinese to name just a few. We expect that as this project develops we will expand to further languages – to ensure that our new, original songs are as singalong-able and accessible as possible – with the added bonus of providing families a chance to learn songs in another language.”

The beauty from a catalogue owner’s perspective is that the music that appeals to kids is evergreen and there is a new audience for it arriving literally every day. The same songs that appealed to children a century or more ago (‘Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star’, after all, was written in 1806) still appeal to children today.

“There are kids that go through this discovery of lullabies, nursery rhymes, counting songs, times tables songs – it’s a never-ending circle,” says Dyson-Jones. “But they very clearly step off it and transition into the next part of their musical development. It is part of the formation of education – and will always be. So kids’ content for me is an excellent target for acquisition and I would always be looking for more.”

1 comment

How would a children’s songwriter get hold of this company?