Lyrical battles are more commonly associated with underground hip-hop, but earlier this month the mother of all lyrical beefs erupted between Genius and Google.

The story has more twists and turns than the plot of a prog rock concept album but, in brief, annotation platform Genius accused Google of harvesting the lyrics it had transcribed on its own site and re-posting them in its search results for when users wanted to read the lyrics from particular songs.

“Over the last two years, we’ve shown Google irrefutable evidence again and again that they are displaying lyrics copied from Genius,” wrote Ben Gross, chief strategy officer at Genius, in an email to the Wall Street Journal.

Genius Media Group claimed its “GOTCHA!” moment was down to the fact that it has a bespoke formatting system for the use of apostrophes in lyrical transcripts, effectively watermarking them. By oscillating between straight and curved apostrophes, a sequence from a transcript would spell out in Morse Code the phrase “red handed”.

This all has echoes of the phenomenon of the “trap street” in the world of cartography where fictitious streets are added to maps and, if copied by another map company, stand out as a smoking gun.

Genius is claiming it only went public on its plagiarism accusations after telling Google back in 2017 (and again in April this year) that lifted transcriptions were appearing online, pointing out this violated its terms of use.

Google has a partnership with LyricFind dating back to 2017 and the latter published a blog on 17 June addressing the issues.

“LyricFind invests heavily in a global content team to build its database,” it wrote. “That content team will often start their process with a copy of the lyric from numerous sources (including direct from artists, publishers, and songwriters), and then proceed to stream, correct, and synchronize that data. Most content our team starts with requires significant corrections before it goes live in our database.”

It did, however, admit that lyrics were possibly “unknowingly sourced from Genius lyrics from another location” by its content teams, but pointed out that it has 1.5m lyrics in its database and only 100 from Genius were under dispute. It added it spoke with Genius before this all blew up and offered to “remove any lyrics Genius felt had originated from them, even though we did not source them from Genius’ site”. LyricFind claims Genius did not respond to this offer. It added, with barrels of snark, that Genius has “no ownership of the lyric rights – music publishers and songwriters do”.

Having initially denied any wrongdoing, Google published a blog a day after the LyricFind one, outlining its position. “Here’s something you might not know: music publishers often don’t have digital copies of the lyrics text,” it said. “In these cases, we – like music streaming services and other companies – license the lyrics text from third parties. We do not crawl or scrape websites to source these lyrics. The lyrics that you see in information boxes on Search come directly from lyrics content providers, and they are updated automatically as we receive new lyrics and corrections on a regular basis.”

It added that it had “asked our lyrics partner to investigate the issue to ensure that they’re following industry best practices” and that it was moving to include attribution details to lyric searches, making it transparent which third-party company provided them. “We will continue to take an approach that respects and compensates rights-holders, and ensures that music publishers and songwriters are paid for their work,” it said.

While all this played out in public, all sides (so far, at least) have managed to avoid going down the litigation route and are probably looking at what is currently happening with Wixen and Pandora and thinking to themselves, “There but for the grace of God…”

Wixen – which represents songs by a multitude of acts including Tom Petty, The Doors, Sophie B Hawkins and Neil Young – has filed a suit against Pandora, claiming it is using their lyrics without permission and it has been looking to resolve this since last year.

“Pandora has built its business in large part on unauthorised uses of [Wixen’s] musical compositions by displaying the lyrics to the musical compositions on its service, including on its website and app,” says the suit. “Pandora does not have any valid licence or other authorisation to display any of the musical compositions in this manner. Nonetheless, Pandora has displayed and continues to display the lyrics to the musical compositions without any valid licence or authorisation from plaintiff, even after receiving notice of the infringement from plaintiff’s representatives in early 2018.”

Pandora argues that it has deals in place, including one with LyricFind; but Wixen is arguing that it itself has no deal with LyricFind for its writers. “[A]s Pandora knows, and has known, LyricFind did not have the authority to grant licences to Pandora for the display of any of the lyrics to [Wixen’s] musical compositions on its service,” it says.

This is all the long way round to show how lyrics have never been more important – and never more contested – than they are today.

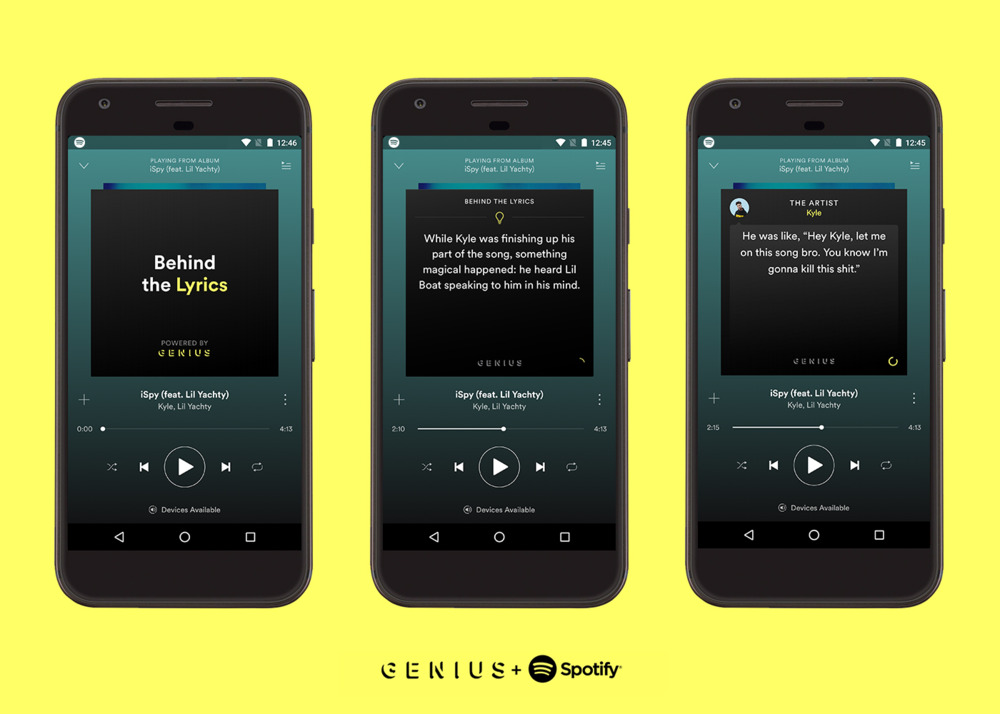

Lyrics are front and centre in a way they were not before. Spotify already has a ‘view lyrics’ option in its app for certain songs – Behind The Lyrics – which has been powered by Genius since 2016 and adds in background details on the song alongside lyrics that, karaoke-style, appear in time as the song plays.

That deal continues despite Apple Music signing up with Genius in October last year for the former to be the official music player on the latter’s site and iOS app.

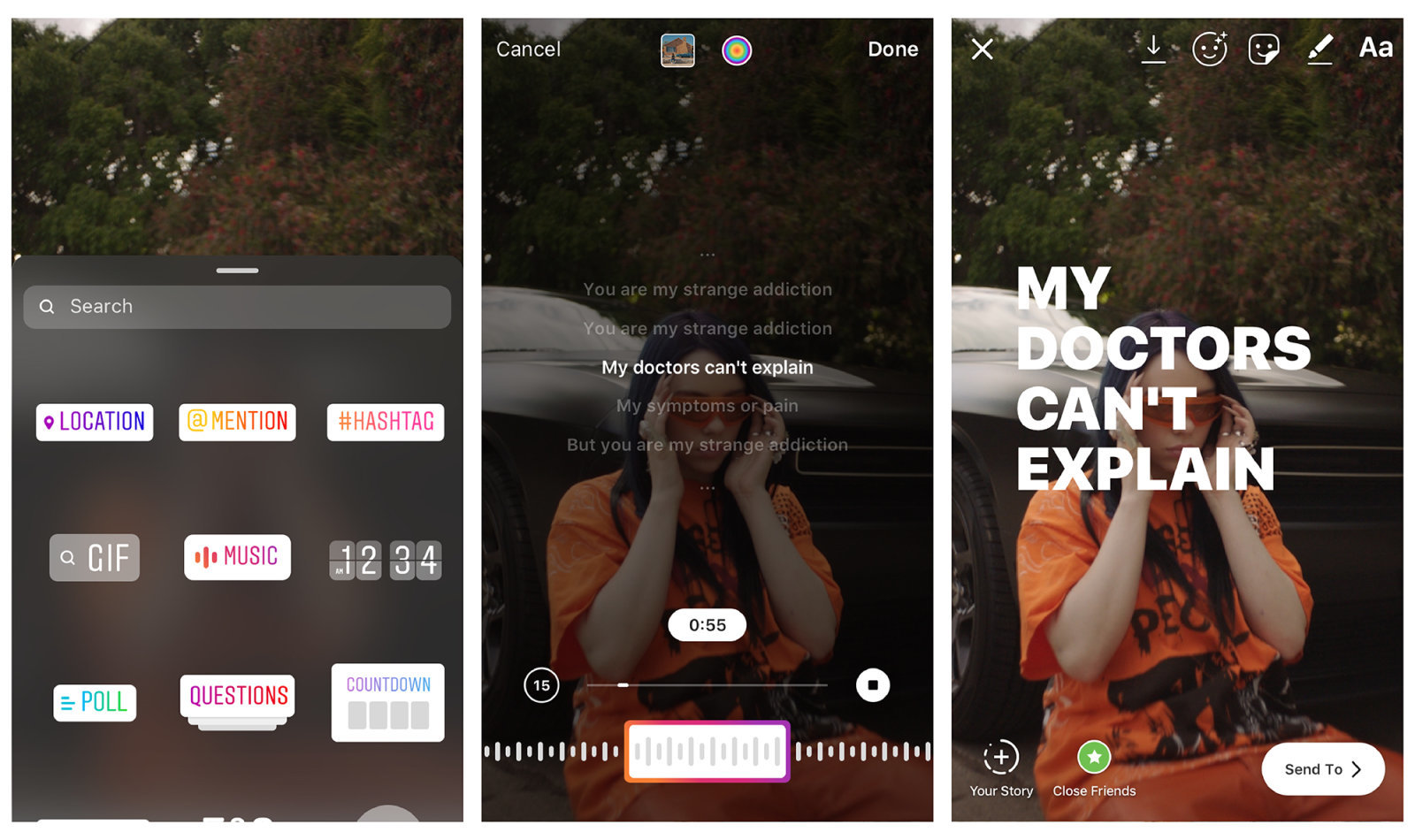

This might be read as Apple Music trying to slipstream its Swedish rival, but Spotify was not even the first DSP to do this – Deezer was, way back in 2014. Now it has just expanded its LyricFind deal to its smartphone app that lets users share up to five lines of lyrics from a song to the Stories feature on their Instagram account and their followers can then play the track in full from Deezer.

This is linked to the existing deals Instagram and parent company Facebook have with publishers whereby lyrics were recently added to Instagram’s music stickers that mean users can add music to their Stories. “You can search from a library of songs and choose the one that best fits your mood in the moment,” said Instagram in a press statement on the deal. “When you search for the part of the song you want to use, you’ll now be able to use the lyrics as a reference point to see where you are. If the song has lyrics, they will automatically pop up.”

It’s not just the DSPs steaming in here to have lyrics as an add-on for their offerings. Lyrics have long been licensed for use on merchandise and other consumer products, including clothing and greetings cards; but this licensing to physical products is now starting to bleed into the digital realm. Last October, LA start-up Via added dynamic QR codes to merchandise items that quote lyrics, such as T-shirts. The lyrics themselves come with a time stamp (showing where in the recording of a song they appear) and the addition of a QR code means they become a new way to re-open connections with the purchaser.

“We’ve created endless options for artist merchandise by using lyrics and citing the exact time stamp they were recorded,” it says on its profile on AngelList. “This turns every lyric into a product and allows fans to express themselves through the music they love. We’ve added a fashionable, dynamic, QR code to each piece of merchandise. This way fans can scan their personalised merchandise overtime for access to rewards such as concert tickets or new music.”

On a similar theme – using lyrics in new and interesting ways digitally – Japanese startup Cotodama is also worth keeping an eye on. Last July, it joined the Abbey Road Red incubator to help refine its offering and its technology. It takes a song’s lyrics and draws on “a proprietary Expression Engine algorithm which uses song structure and mood data to determine how to animate the lyrics for each song played”. It is already working with Universal Music Group to generate lyric videos for the major’s acts and has also created the Lyric Speaker Canvas that displays moving lyrics on a screen as you play music through it.

Beyond the actual licensing and accreditation that really should be a given here, it’s not always the case that the annotations around lyrics are on the money. In April, Hayley Williams of Paramore called out Spotify, saying that some of the facts presented on the Behind The Lyrics feature for their song ‘Hard Times’ were, in fact, incorrect and that the band’s management had been trying to get Genius to change them – but to no avail. Spotify responded by saying it would amend them – but only after being directly called out by Williams.

With lyrics back at the top of the agenda again, the hope is that the importance of full accreditation (and licensing) is stressed to all those already active in this space as well to as those at the startup stage who are drawn to an area that is enjoying something of a boom time at the moment. The fact that Genius raised $15m in new funding just over a year ago (saying “our mission at Genius is to be the No.1 brand in music”) is sure to add to this tech gold rush around lyric services.

The rapid expansion of LyricFind into Brazil and 38 markets in Africa last year – as well as Southeast Asia, the Middle East and North Africa this year – shows the ambition for companies in this space as well. It also shows the importance of having localised offerings in each market rather than a blanket service where English is the default (or only) option. Platforms are global and so lyrics will have to become polyglottic.

Amid this international and linguistic expansion, it is imperative that all lyrics are fully licensed and credited – and how the Wixen/Pandora legal dispute is eventually settled could stand as an important test case here. It is also imperative that any annotations are correct. If pop stars publicly state information is wrong, service credibility is at threat and this could cause more reputational damage than any licensing spat.

Deals and licensing disputes can always be smoothed out, but it’s the consumer who will make or break lyric companies. If they are not singing from the same lyric sheet as the services, all the words in the world won’t fix this.