Music industry standard-setting organisation DDEX held back to back its 36th Plenary Meeting and 2nd Creator Credit Summit in November, both as virtual events. The Creator Credit Summit featured over 30 speakers, including composers, producers, engineers, representatives from record labels, distributors, and international rights organisations, over three consecutive days.

Topics included themes addressing different aspects of creator credits and tools to assist in their proper use, such as proper identification and payment; the conundrum of entering credits in the recording process; DIY musicians and metadata; and music metadata in audio/visual works.

The Summit also included presentations from seven companies (Creative Passport, Jammber, Muso.ai, Quansic, Session, Sound Credit, and VEVA Sound) that provide tools helping creators deal with data issues, all of them incorporating the DDEX Recording Information Notification Standard (RIN). Here are five takeaways from the Summit.

1 – Standards matter

Mark Isherwood from DDEX’s Secretariat (pictured above), summed up best in his introduction the importance of a common set of data for the music industry: “DDEX defines the lingua franca for the music industry.” It’s a data language that allows different parts of the industry to interact, and eventually for rights holders and creators to get remunerated.

“DDEX standards cover a significant part of the industry and business transactions have a DDEX standard to support these transactions,” said Isherwood, who added: “If you don’t speak DDEX, getting information from partners is going to be tricky.”

But Isherwood also added a note of caution: For the system to work, it all depends on where the data originates. If the data is from unreliable sources or badly entered, the system cannot function. It is up to all the various stakeholders to play their role in ensuring that data is accurate and also collected as early as possible in the process. “Metadata is a love note to the future,” concluded Isherwood.

2 – Give credit where deserved

In the digital world, one set of information that has often disappeared with the convenience of all-access music on streaming services are the credits that, well, give credit to all the people involved in the various aspects of the recording of music. No one better than Jimmy Jam, one half with Terry Lewis of the production duo Jam & Lewis, made a better call for the value of credits.

“I was always intrigued at the little names of songwriters, producers, engineers,” at the back of the record covers, said Jam, in conversation with Maureen Droney, Sr. Managing Director for the Recording Academy Producers & Engineers Wing. He recalled that the first time he paid attention to credits was when he looked at a record from the Supremes and saw Holland-Dozier-Holland in the credits box. “For me, Holland was a country,” he joked. “And my mom said these were the names of the songwriters.”

“It was always fascinating to me to see that there were certain groups that I liked and some records that sounded different,” he explained. “I was getting information as I was listening and that was part of my musical education.” In 1982, Jam & Lewis co-wrote their first hit, ‘High Hopes’ by SOS Band, which was engineered by Steve Hodge. “We knew the name Steve Hodge through looking at liner notes of albums from bands like Shalamar. So who is the engineer, and where did he record? That’s what we did. If it weren’t for the liner notes we wouldn’t be here.”

“If it weren’t for the liner notes we wouldn’t be here.”

– Jimmy Jam, Jam & Lewis

Following that first hit, Jam & Lewis became much in demand songwriters and producers, working with the likes of Janet Jackson, Patti LaBelle, Alexander O’Neal, Boyz II Men, Mariah Carey, to name but a few. But for Jam nothing felt better than seeing his name in the credits of a recording. “I loved it when I saw my name in the credits, it’s like listening to your song for the first time on the radio, it was a thrill,” he said.

For Jam, listing all the names of the people who worked on a project gives a sense of where the music is from and the people behind it. “To see all those names to me gave music something we lack now because music seems to appear out of nowhere and you don’t think it needed a bunch of people to get it there,” he said.

Hence his call for people to take seriously the need to enter credits at all stages, particularly during time in the studio. He’s been an evangelist on behalf of the Grammys, which use credits for the nomination process, to convince artists to take credits seriously. “People use the information that is in the credits, so if the information is there you are going to be part of the process, and it can only go as far as what is given to us,” he explained.

Overall, Jam said he believed that standardising data “makes sense” in the digital age where data will determine what gets to the DSPs and how people will be paid. “In the old days of track sheets, you had something physical, and now with digital, it needs to be entered and we have to keep track of everything. This has to be part of your process,” he said.

3 – No data = no money

In the wake of Jimmy Jam’s timely reminder of the importance of credits, the participants in the session ‘How credits improve contributor identification and payment’ dug deeper into the data alphabet soup and the need to get data right.

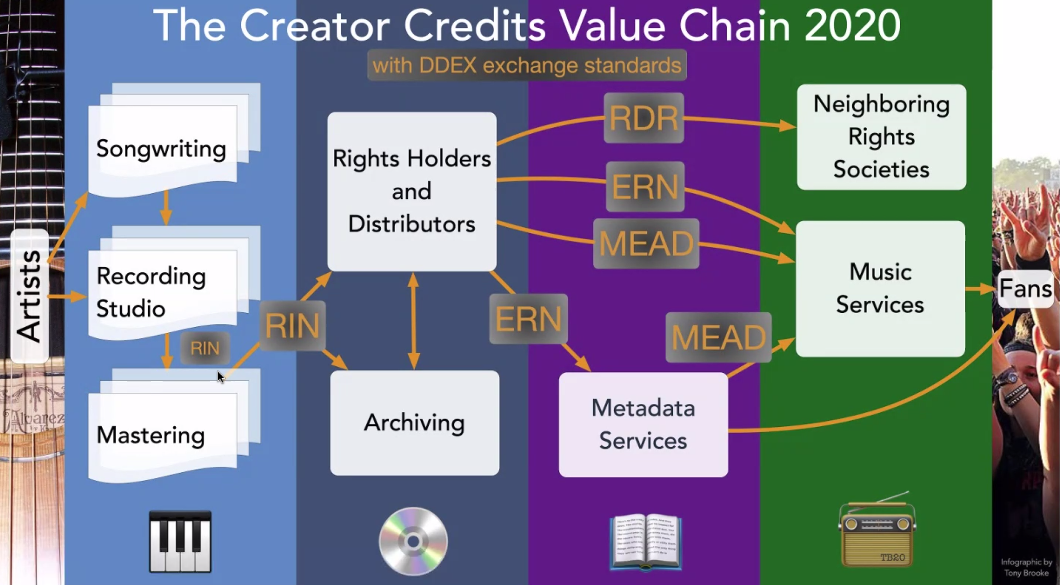

“Credits were on the back of an album, today we have a much deeper set of information,” said moderator Tony Brooke from Warner Music Group who emphasised the importance of standardised identifiers such as ISNIs (International Standard Name Identifier), IPIs, IPNs, as well as the ISRCs (recording) and ISWCs (composition). “It is really important that credits include identifiers,” said Brooke.

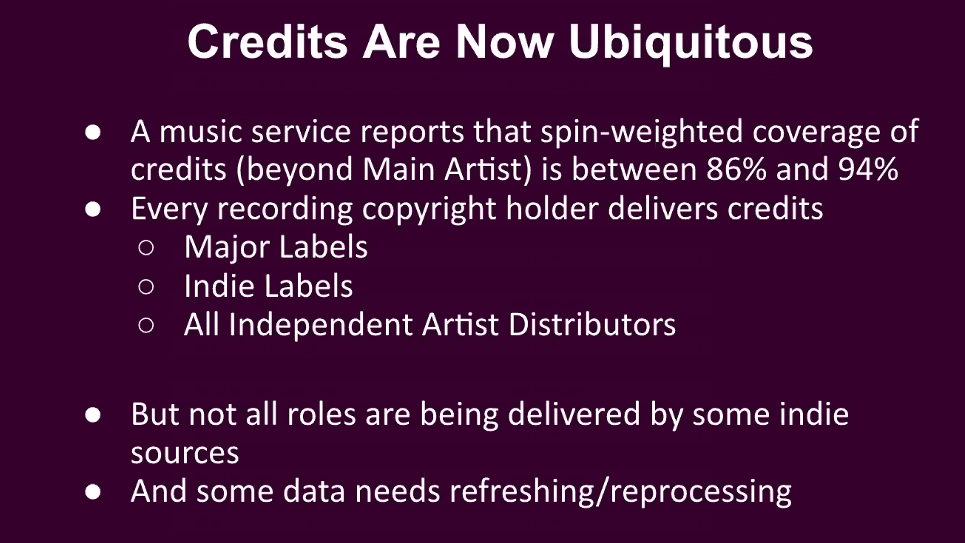

“Credits are no longer a rarity, they’re ubiquitous,” he added, noting that music streaming services are increasingly displaying credit information to help consumers access music through different angles, such as the producer of a recording or the songwriter(s). “Music services are showing this data,” he said. “Spotify is a leader in this space: who wrote the song, who produced it, and they make links to other works. It is super cool and very hard to do unless you have identifiers.”

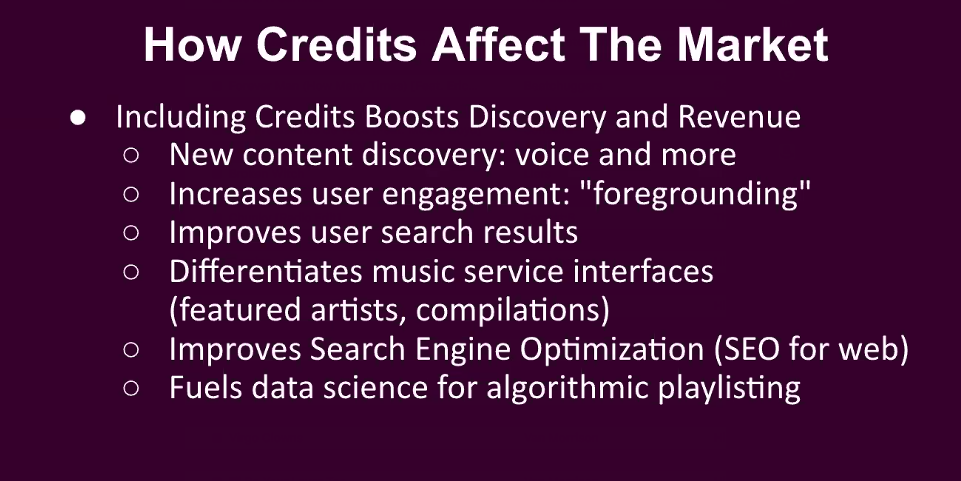

Why does it matter and how do credits affect the market place? For Brooke, having the proper credits “boosts discovery and revenue, helps new content discovery, increases user engagement, improves user search results, is a way to differentiate music service interfaces, improves search engine optimisation, and fuels data science for algorithms used for playlists.”

Dae Bogan, head of third party partnerships at the Mechanical Licensing Collective, noted a particular example: “There are a lot of session musicians who are not aware there are entitlements and for that they need credits,” in the case of neighbouring rights paid to non-featured artists.

So how to ensure that all the data is properly captured and entered? Bogan is adamant that data should be everybody’s concern. “Metadata has to be captured and distributed to all the different types of sources, and we have to make sure that everyone has that data,” he explained. “Every label and publisher has to make sure the collective management organisations (CMOs) get that data and also the DSPs and third-parties like Gracenote or Audible Magic.”

“Metadata has to be captured and distributed to all the different types of sources, and we have to make sure that everyone has that data.”

– Dae Bogan, Mechanical Licensing Collective

This point was also picked by Adam Gorgoni, a composer and founding member of Songwriters of North America (SONA). “With neighbouring rights, there is money out there, but you will only get it if you are properly credited as a side musician or if you have participated in the production. If the credits are not there, you won’t get paid.”

SONA, he said, is engaged in educational programmes to inform songwriters about the importance of “having their data straight.” SONA has even set up SNAG: the sexy metadata action group. He admits that data is not necessarily a conversation that creators want to have. “You are talking to creative people who have no interest in metadata,” he said. “We are in a creative process, and it is hard to talk about splits and various data points. This is not the most creative conversation but we push songwriters at large to do it because the data collected in the studio is crucial.”

“This is not the most creative conversation but we push songwriters at large to do it because the data collected in the studio is crucial.”

– Adam Gorgoni, Songwriters of North America (SONA)

However, what has changed also is the creative process, which can affect the way data is captured. “Now for younger artists, making songs is a collaborative process. They don’t even think in those terms. The creation of tracks and melody all happens at the same time and they’re not sure who did what,” said Gorgoni.

For Sara Jackson, VP of US administration at Kobalt Music Group, good data “improves the bottom line” and “definitely increases revenues and visibility.”

4 – A cue sheet is the holy grail for AV and music metadata

Anyone who has been involved in music for film and TV knows the importance of cue sheets. These are documents that list all the various music segments on a show or a film, and the more accurate they are, the more likely anyone who contributed will be paid when the movie/TV show is played, streamed, downloaded, etc. This requires capturing data at source about music used in audio-visual productions for the various players along the value chain.

For the speakers on the panel ‘Music and audio-visual production – a different spin on metadata’, the answer was that more collective work from all parties would ensure that data is listed correctly in the cue sheet, and then cue sheets have to be standardised so that studios as well as DSPs and CMOs work from the same, well, sheet…

Nick Osztreicher, Director of Music at Netflix, said the key issue with cue sheets is about developing actionable business solutions, and cue sheets are part of the process. A service like Netflix supplies cue sheets into the CMO system, and standardisation would indeed help. “Adoption has to be driven by societies; we can create the files but people have to accept them,” he said.

“Adoption has to be driven by societies; we can create the files but people have to accept them.”

– Nick Osztreicher, Netflix

The session happened the day the International Confederation of Societies of Authors and Composers (CISAC), teaming up with music publishers and producers through the Society Publisher Forum (ICMP, IMPA, IMPF, AIMP), announced the Cue Sheet Standards & Rules that will “harmonise music cue sheets” and simplify the rules governing the identification of musical works used in audiovisual productions.

“Standards are something we all want.” said Osztreicher, who added that Netflix brings a layer of complication as its business is global and “things have to apply globally, and it is not easy because of the scale, in that we have so many productions.”

He continued: “Cue-sheets vary depending on types of production and the years they were created and who was responsible. We have to add a layer of rigour on that: we have to have complete information so as responsible distributors we can pass on that information [to CMOs].”

Accuracy is what CMOs need, explained Helena Segersten from French rights society Sacem. Like many other CMOs, Sacem licenses video-on-demand services (since 2010 in the case of Sacem), and its goal is to make sure that the works of its members are protected. “We take data from services and match it with what we have registered in our database and then distribute to our members,” she said. Hence the need for accurate and operational data. And quite often the data is, as she put it, presented in “exotic formats” that do not necessarily contain all the data. Hence the importance of CISAC’s harmonised cue sheet. “We now want to promote the [CISAC cue-sheet] around the world,” she said.”It is a step towards a standard.”

“We now want to promote the [CISAC cue-sheet] around the world. It is a step towards a standard.”

– Helena Segersten, Sacem

Reacting to the conversation in the chat box, Teri Nelson Carpenter, founder of Reel Muzik Werks, wrote: “The Cue Sheet Standards & Rules simplifies the rules governing the identification of musical works used in audiovisual productions. The harmonisation improves the administration of music rights, brings a new consistency to the use of cue sheets, and will lead to increased efficiencies and potentially reduced costs for rights holders and users.”

5 – Someone has to take responsibility for the credits

So how can stakeholders make sure data is collected and attributed properly? Participants in the session ‘Entering credits in the recording process: Whose job is it anyway?’ simply agreed that “it’s everybody’s job.” According to The Recording Academy’s Maureen Droney, it is the responsibility of the producers, the engineers, the musicians, and any party who is involved in the creative process.

“You don’t want to be talking about the money as you make music but this conversation needs to happen,” she said, adding that it would be the time to set up a new role of data assistant, whose role would be to collect and research all the occurrences when music was made, by who and where.

“You don’t want to be talking about the money as you make music but this conversation needs to happen.”

– Maureen Droney, The Recording Academy

Producer, mixer and engineer Cameron Craig, executive director of The Music Producers Guild, says the data gathering process can be complicated by the use of multiple studios and engineers, and the fact that not all the information is collected at the mixing stage. But for him, the key issue is that “a lot of education needs to happen and session musicians need to get involved at an early stage.” “We need to educate people as to why it is important,” he said.

Record producer Sylvia Massy concurred that the “studio is not an exclusive place any more” where music gets made. As a producer, her role is “to make sure credits are recorded” but due to the lower budgets, producers rarely have the means to keep an assistant on the payroll to write down all the credits as they happen. “So much data gets lost,” she said.

For Massy, the answer of collecting the credits must be collective, with all participants chipping in. There are now systems helping artists and producers entering data from the point of the recording but it still needs to be entered. And again, there’s an incentive to doing it: “If credits are entered early we all get paid,” said Massy.

Artist manager Jr. Regisford, a principal at New Heat/New Heights Entertainment and co-founder/head of music of World of Dance Records, said it is often now the responsibility of the manager to ensure that all credits are properly entered. “I end up being responsible for helping producers track everyone down,” he said. “We have a template of what we need to get and we fill the blanks. It ends up being a group effort. Some producers are more on it than others, That’s how we do it, we piece it together.”

Labels have also a role to play, as explained by Craig Rosen, Executive VP of A&R at Atlantic Records: “As the label, we are really the receivers, the collectors, and the fact checkers of the information as it comes in,” he said. “We serve as proxy for the artists insofar as collecting credits for the artists.”

“As the label, we are really the receivers, the collectors, and the fact checkers of the information as it comes in.”

– Craig Rosen, Atlantic Records

Like other speakers, Rosen said the process is somewhat complicated by the way music is recorded these days, and also the fact that some artists finish a track on a Wednesday and drop it on a Friday, before all the data gathering has been concluded. “So much has changed since jazz sessions where you got into the studio, recorded three sessions and then picked a cut. That was easier,” he explained. “Today, records can be made in variety of ways and there is more of a possibility that no one is really sure what ended in the final mix and where it came from, or not sure who wrote more than the other, whose backing vocal it was, or which guitar solo it was, or if it was from the demo!”

Rosen said that updating credit is now a regular process and more data is unveiled as the information circulates, but he added, “It is important that whoever receives the credits needs to understand that we live in dynamic world and first batch of data should be as correct as possible and then people have to adjust to that.”