Introducing Music Publishing in the Age of the Songwriter, a new report from Synchtank.

Following on from our 2021 publication Drowning in Data, the report examines the fundamental shifts in the music industry in recent years and what they mean for the future of publishing, from new deal types and services that promote transparency and equality to creating more value for songwriters in the digital age.

Through interviews with leading executives and songwriters including Björn Ulvaeus, Carianne Marshall, Jon Platt, Mary Megan Peer, Merck Mercuriadis, and Nile Rodgers, the report delivers the most comprehensive analysis of the music publishing industry from the perspective of those leading it and the songwriters it serves.

This is the third instalment of the report, which is being released in the following four parts:

- The Evolution of Music Publishing

- Future-Proofing Publishing Services

- Economics, Transparency and Equality

- Digital Drivers of Growth

Part 3 – Economics, transparency and equality

3.1 The economics of streaming

The boom in streaming has helped return the industry to growth after, particularly for the recorded music sector, a decade and a half of steep decline since the turn of the millennium.

While the labels may be celebrating the streaming-powered windfall they are currently enjoying, publishers and songwriters are seeing streaming as equal parts blessing and curse.

The positives here are numerous: streaming pulled the industry out of a nosedive; streaming has made everything (pretty much) available at all times, which means that songs can theoretically earn for their life of copyright and not just when they are released or marketed; streaming is breaking down old geographic barriers and bringing on stream whole new markets that were either minor or effectively unreachable in the analog world; streaming has helped democratize music even more as anyone can get their music out there for minimal costs; the fact that songs are now a powerful asset class can be attributed to the many changes, as well as the economic growth, that streaming has helped bring about.

The negatives relate primarily to how these spoils are carved up and shared out.

(This perceived inequality in how revenues are split was brought into sharp contrast during the pandemic when entire income streams were suddenly cut off and many songwriters were making it clear in public statements that the income from streaming royalties was not enough to help them stay afloat during this time.)

In the media (and across social media), more and more songwriters are outlining their grievances with the way in which streaming revenues are paid through, often explaining that hit singles are far from the economic windfall that the public might presume.

“I have so many writers signed to my publishing company who have songs with 200 million streams, 50 million streams, 100 million streams, and they can’t pay their rent,” is how Justin Tranter (Grammy Award-nominated songwriter and producer, founder of Facet, activist and GLAAD Board member) explained the harsh reality for many. “The middle class of songwriters has been completely decimated.”

There has been mounting criticism of the cold reality of streaming income from many songwriters for several years but the pandemic saw them explain in harsh terms just how brutal it can be, pointing out to the public that streaming success does not always translate into economic success.

“A songwriter I know had a song on a gold-selling album, and asked the label if they could send her a gold record to put on the wall of her studio,” says Helienne Lindvall, songwriter and President of the European Composer & Songwriter Alliance. “They told her she’d have to pay the £200 cost of it – and that was actually more money than she’d made off that song.”

The streaming-led pivot into a track-based economy is also shifting the economic ground rules for songwriters. As albums start to be atomized and lose their currency, the old model where mechanicals were paid equally across all tracks on an album is being erased. Today, unless you are writing on a series of mega hits, getting the streaming numbers to add up is increasingly difficult.

“In the world of physical products, the $15 someone would pay for my CD is the same as the $15 someone would pay for Taylor Swift’s CD,” says Michelle Lewis (singer, songwriter, composer, music creators’ rights advocate and co-founder of SONA, Songwriters of North America).

Coupled with this is the fact that hit songs tend to have multiple writers involved in their creation, meaning the revenues due to songwriters are being split even more ways. As noted in Part 2, Rolling Stone found in its analysis of the top 50 songs from the past decade that an average of five writers are involved in crafting a hit song. This boom in collaboration is a catalyst for new types of creativity, of course, but it also means the available revenues have to be divided up in more ways.

Running in parallel with this is the mounting volume of new music being released that is added into the 80m+ tracks already on DSPs. A commonly cited figure is that 60,000 (or even 70,000) new tracks can be released a day. Keeping your head above the waves of these rolling oceans of songs gets harder as every day passes.

In short, there is more music out there than ever before and the industry is making more money – but there are more songwriter mouths to feed.

The harsh reality here is that some songwriters have the scale to compete in this new streaming reality, but most songwriters (unless they are the architects of a vast number of enormous global hits) do not.

“The business model for digital streaming rewards scale with its weighted rates and payouts based on market share, and this is where publishers are the least aligned with songwriters,” argues Michelle Lewis. “Publishers have rosters of talent and large catalogs containing hits. And hits and the big catalogs make the majority of the money. Songwriters just have themselves, and only the top 1% of us have the volume of hits in our catalogs to come anywhere close to reach the kind of scale it takes to make money from streaming. This creates a huge empathy gap – a disconnect, because publishers are seeing increasing revenues and record profits while songwriters’ complaints are growing louder about how broke we all are.”

Songs remain the most important currency in the music business, but songwriters are the lowest compensated party in this equation. All songwriters we spoke to agree that this has to change; and it has to change both significantly and quickly.

As legendary songwriter producer and co-founder of Chic Nile Rodgers puts it, “We [the songwriters] sit at the bottom, even though the thing that we make is what the whole industry is built upon.”

It is important to take a longer view on the changes here and not simply presume that publishing and songwriting were always being dealt a terrible hand here. It is essential to look at how things have changed in recent years and how older revenue models have shifted.

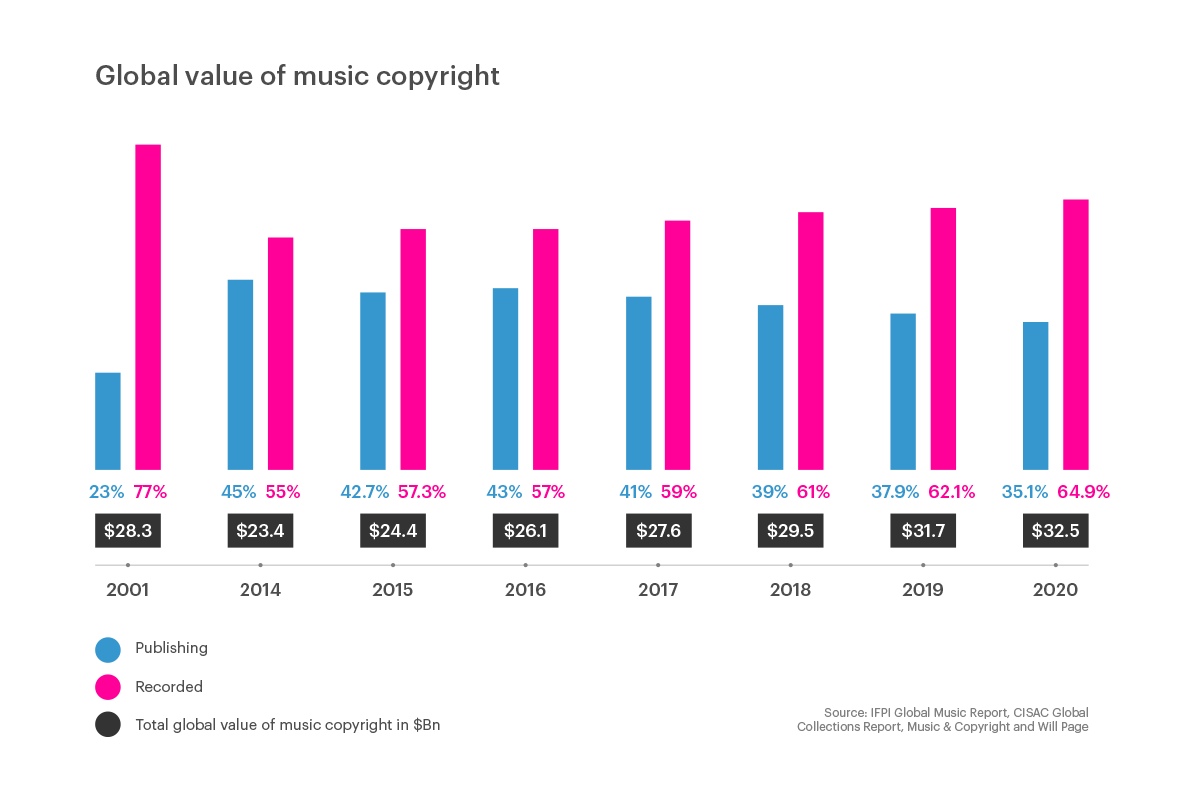

In his work on measuring the global value of music copyrights, economist Will Page has produced fascinating numbers that show how publishing’s share of the pie has changed from the pre-streaming age to today.

From this, we can see that in the dawning of the digital age (as well as the digital piracy age), publishers were taking just under a quarter of the value of global copyrights. By 2014, however, their share was up to 45%. Since then, in part due to the impact of streaming becoming the dominant format for recorded music, that share of the total copyright pie has slipped; but is still a significantly bigger slice of the pie in 2020 than was being cut for publishers in 2001.

Publishers and songwriters will, of course, say things were better in 2014, but since then things have become steadily worse for them in terms of overall splits. The presumption is that they will become steadily worse in the years ahead.

Recording artists will step forward at this point and argue that songwriters have always had much better splits with publishers than recording artists have had with labels. In a co-publishing deal, for example, 20-25% of revenues would typically go to the publisher and the rest would be split between the writers. In stark contrast, recording artists might be getting a royalty rate in the teens (or a bit higher if they are lucky/a megastar who has renegotiated) while the label takes the lion’s share.

Ultimately, the streaming model benefits labels the most, although they will argue they are the ones investing most heavily in promotion and marketing. That said, huge label costs in the past such as the manufacturing and distribution of physical products are greatly reduced in a market that is predominately digital. Other label overheads such as marketing and advertising in the digital era can also be done more cost-effectively compared to two decades or more ago.

“Record companies don’t have the huge financial exposure that they used to have,” argues Nile Rodgers. “There’s no longer breakage, manufacturing, shipping, returns and many more of the costs that were built into getting products out. With streaming – bang! – you deliver the master and the song’s all over the world. There’s also far less risk in the signing of new artists through data, research and social media. This is the perfect opportunity to fix a system that’s always been geared to not being fair to the most important pillar in this business, which is the song.”

Songwriters might have more favorable deals with publishers than recordings artists do with labels, but if that split is a fraction of what the labels get, they will rightly feel aggrieved.

“I had the head of an independent label tell me that their costs have gone down by 50% thanks to streaming,” claims Helienne Lindvall. “And I think these massive bonuses that Universal paid out just really shines a light on it. It’s like living on two different planets. As a songwriter, you just feel like, ‘Oh my God, everyone in this business is making more than the people who actually make the music.’”

Much of the debate here links back to issues of transparency – properly seeing where all the money coming into the business is, then tracking exactly how that is carved up and what share eventually makes its way to the bank accounts of songwriters.

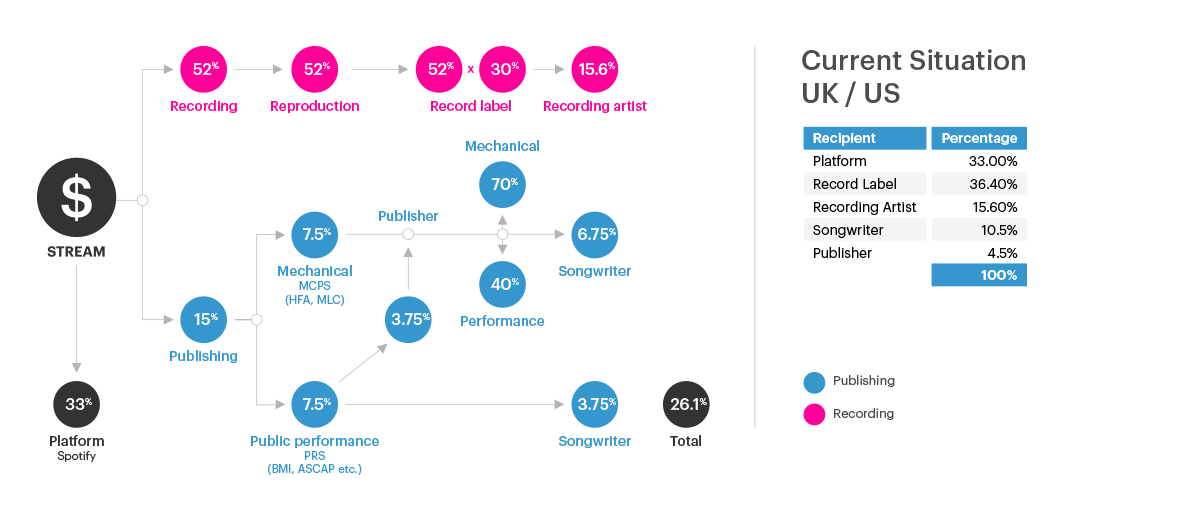

Chart showing the current situation with regard to the division of streaming spoils between Spotify / record label / recording artist / publisher / songwriter (Source: CC Young & Co)

The debate around transparency in the music industry is far from new. From the earliest days, debates about contractual terms and obfuscation of rights and payment flows have dogged the sector.

The issue, however, has never been as central or as loudly debated as it is now.

That is because there is a tense dichotomy at the heart of digital: on the one hand, it was supposed to make things clearer as every use could be tracked; on the other hand, it has made things more complex to audit and understand.

In 2021, Synchtank called its report Drowning In Data for a reason: in an age of multiple platforms and billions of lines of micropayments, understanding this world is becoming incrementally more complex.

The issue of equitable payments in this new – and more convoluted – world has also become incrementally more heated.

In the US, the battle lines are being drawn around the CRB – with publishers and songwriters calling for a greater share of the booming streaming market while the DSPs are simultaneously pushing for rates to be either frozen or reduced.

As we were finalizing this section of the report, a major breakthrough happened in the US with regard to the CRB III rates covering 2018 to 2022. On 1 July, David Israelite, the CEO and President of the NMPA, confirmed: “Today the [CRB] reaffirmed the 15.1% headline rate increase we earned four long years [ago], confirming that songwriters need and deserve a significant raise from the digital streaming services who profit from their work.”

The implications here are enormous. As Music Business Worldwide put it, “The streaming services are about to fork over a whole bunch of cash to publishers and songwriters to cover the now-officially increased CRB rates for the years 2018-2022.”

(Steps will begin later this year to agree the rates for 2023 through to 2027 – aka CRB IV – and will be fiercely contested on both sides, especially in light of the 2018-2022 ruling.)

The sums at stake here are staggering. At the NMPA’s AGM in June 2022, Israelite argued that, based on revenue and subscriber projections over the next five years, the difference between what the NMPA are proposing and what Amazon and Spotify are arguing for totals more than $7.8 billion.

Throughout the whole process, the voices of the songwriting and publishing community were being aggregated and amplified like never before. The CRB III ruling is affirmation of the power of this concentrated and collective lobbying by the publishing sector.

“The best way for us to bring value to our writers is to fight for increasing the rates for streaming and we’re very active in the industry on that,” says Mary Megan Peer, the CEO of peermusic about CRB IV. “Right now we are one of four publishers, we’re the only independent, testifying in the United States CRB IV rate trial which will set mechanical rates for 2023 to 2027; it’s a four-year term. We also put industry activities like that as an important piece of our growth strategy.”

She adds, “The DSPs are really trying to argue that the pie is already fully divided up in that case and our sliver is all that’s left for us. We believe that the pie can be much larger than they claim.”

Golnar Khosrowshahi, CEO and founder of Reservoir Media Management, insists that this will be an ongoing battle and that it has to be fought on many fronts.

“The industry has struggled to create what could be interpreted as adequate revenue streams for creators,” she says. “We continue to advocate for fair compensation […] Our hope [is] that we have gradually moved to better compensation models, increased compensation for songwriters. This is something that we’re going to be battling for a long time. And it’s an effort that will continue. I don’t think there’s going to be a moment where we’re not in some capacity or another, not advocating for creators.”

No one in the publishing world is denying the importance of streaming and how it has helped turn around a decade and a half of decline in the record business that began at the turn of the millennium. They are, however, insistent that publishers and songwriters get a more equitable share of the spoils.

“Streaming services saved the industry,” says Willard Ahdritz, the founder and Chairman of Kobalt. “However, we always need to fight for the rates we get paid from the DSPs. How is the value divided between publishers, labels and creators? Here transparency is very important to understand.”

The biggest players in the publishing market are also backing the efforts of the National Music Publishers’ Association here.

“Growth in digital continues to be a bright spot for us and our industry,” says Guy Moot, co-chair and CEO/COO of Warner Chappell. “It’s our role as publishers to ensure our writers are reaping the benefits of this growth and being paid fairly by DSPs, and we continue to push for favorable deals and terms with all of the major streaming services and tech companies. We also work with great partners like the National Music Publishers’ Association to advocate on our songwriters’ behalf. This will be especially important over the next few months as we head into the upcoming CRB hearing with DSPs pushing for the lowest US mechanical rates in history.”

Marc Cimino, Chief Operating Officer at Universal Music Publishing Group, adds, “It’s a constant pull with the digital services to make sure that songwriters are properly compensated as the digital services focus on maintaining and preserving their margins. We recognize as a business what the music streaming services have done to bring us back to a healthy place and it’s in everyone’s best interests for them to be successful. But what DSPs have to recognize is that music has been a massive driver of their valuations beyond the P&L on a service level and it’s been the songwriters and artists who have really been at the forefront of allowing music innovation for these companies. Where would the services be without disaggregation of songs on albums? That has been the single biggest factor in creating a difficult situation for a lot of songwriters and when we are forced into a laborious negotiation or CRB process for what is essentially a rounding error for these companies. It’s maddening.”

Nile Rodgers suggests it will be incredibly difficult to recalibrate the economics of streaming to better benefit the songwriters and publishers as the record labels have had things run in their favor for too long and such thinking (and entitlement) is entrenched in their attitudes and behaviors.

“It’s hard for people to share fairly and equitably when they’ve been used to having an unfair share of the pie for themselves for so long,” he says. “Now is the time to finally recognize that without the songwriter and song there is no music business.”

Mike Smith, Global President of Downtown Music Services, is not convinced the major publishers are doing as much as they could to improve the lot of the songwriter here – and this is largely down to them being part of bigger music companies where the recorded music side of the business takes economic priority.

“I see the majors being very reluctant to give more money to the publishing businesses in terms of the streaming revenues they get because they’re able to hold on to 80% of the revenues that come in for records,” he says. “Whereas they’re only able to hold onto 25% or 20% of the money that comes in for publishing. As a result, the major companies in their negotiations with the DSPs are not really very aggressive in arguing hard for the songwriter. We would like to see a much more equitable split between the publishing and record business. I think that conflict of interest between records and publishing is always going to be a problem for the majors.”

Merck Mercuriadis, founder and CEO of Hipgnosis Songs Fund, argues a very similar line here.

“The world will tell you that the way that a songwriter gets paid in the United States is through legislation – yes, that’s true – but that legislation, as we know, is affected because the three loudest voices in our business aren’t advocating to the extent that they would like to,” he asserts. “But it’s also how a songwriter is affected based on the negotiation that Universal, Warner and Sony are having with Spotify on behalf of recorded music, because they’re not leaving any room for the songwriter. You would think that the recorded music company that owns the first-, second- or third-biggest publishing company in the world would be leaving enough room in the negotiation for the songwriter to be able to be rewarded properly.”

David Israelite, however, takes issue with the line of argument that Mercuriadis is pursuing here.

“Merck is a member of mine [of the NMPA],” he says. “A lot of what he does I applaud and I support. The one specific thing that I called him out on is that he had made a specific criticism of major music publishers – which I thought was just off base – which was the idea that they somehow are not fighting for their songwriters in the same way that maybe he thinks he is or other publishers do. And it’s just not true.”

By way of illustration, he estimates that the costs incurred by the NMPA in fighting for an increase in streaming royalties through CRB III was going to cost $20 million – and much of this was funded by the major publishers. He also says that the costs for the upcoming CRB IV battle could be similar.

“It’s the major publishers that are there on the ground level in that fight,” says Israelite. “I think publishers need to do a better job of engaging their own songwriters, and also publicly, in explaining how this industry now works. In the streaming world, for example, 80% of the money that interactive streaming companies pay – Spotify, Apple, Amazon – for publishing, 80% of it goes to songwriters. So when the publishers are the ones in the CRB funding and leading the fight over what’s going to happen to those rates, 80% of the result of that impacts songwriters, not publishers. I don’t know that the industry has done a good enough job, – both within the songwriting community and larger publicly – of making that clear.”

Ross Golan, songwriter, record producer, playwright and host of And the Writer Is… podcast, also believes the record labels have vested interests in maintaining the economic status quo of the streaming model.

“I think a lot of people let major labels off way too easy,” he argues. “They’re often major shareholders, if not owners, of the streaming services and there’s no question that this is a golden era for the music industry. It’s just not for those who don’t have competitive songs.”

In parallel with lobbying efforts in the US, the UK campaigning by #BrokenRecord resulted in a DCMS inquiry into the economics of music streaming and the feet of both DSPs and record labels were held to the fire. As with CRB, this is a rolling issue and UK competition regulator the CMA responded to the inquiry by launching its own study into the streaming economy and will seek to address the perceived imbalances and iniquities here.

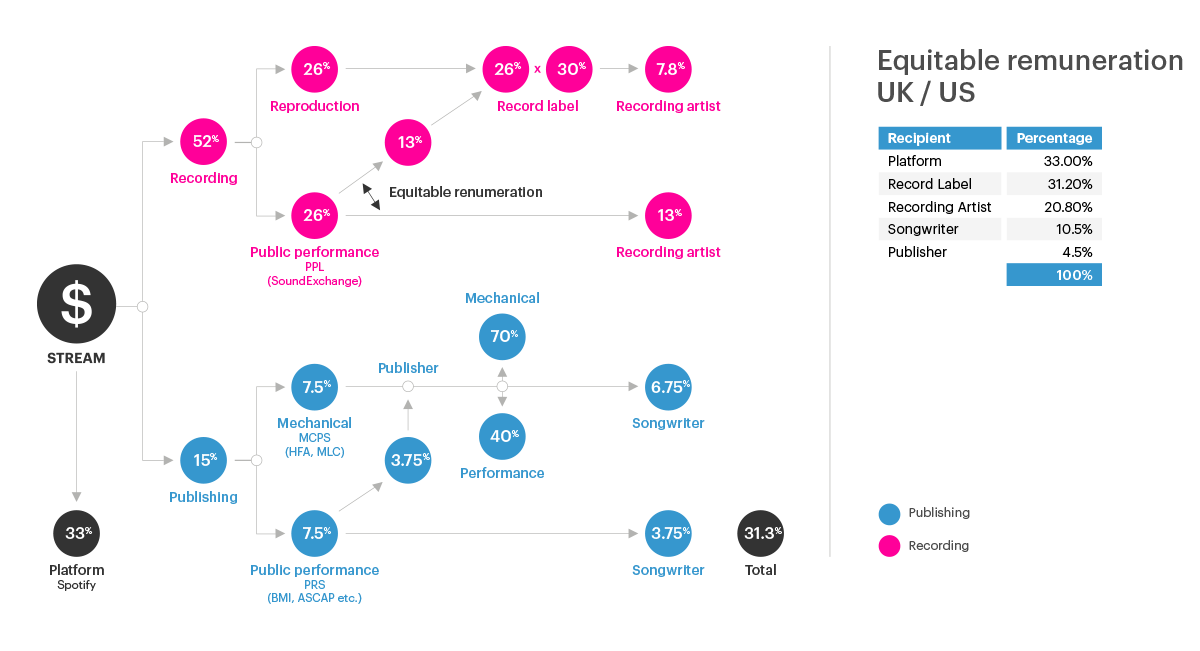

One of the key points that #BrokenRecord is pushing for, and was heavily picked up by Kevin Brennan (the MP at the forefront of the inquiry), was about applying equitable remuneration (ER) to streaming, just as it is applied to radio in the UK. Labels and their representatives pushed back aggressively against ER and a second reading in Parliament of Brennan’s Bill in December 2021 was not passed. Legislative changes might not have happened the way Brennan and assorted campaigners had wished for, but the debate about more equitable payments from streaming is not going away.

Helienne Lindvall, however, points out that ER might be a win for some in the creative community, but not all. “Equitable remuneration in itself is actually more of a performer demand than it is a demand for us songwriters, as there’s no guarantee that it would increase our share, that it would be the same kind of 50/50 split as there is on radio,” she says.

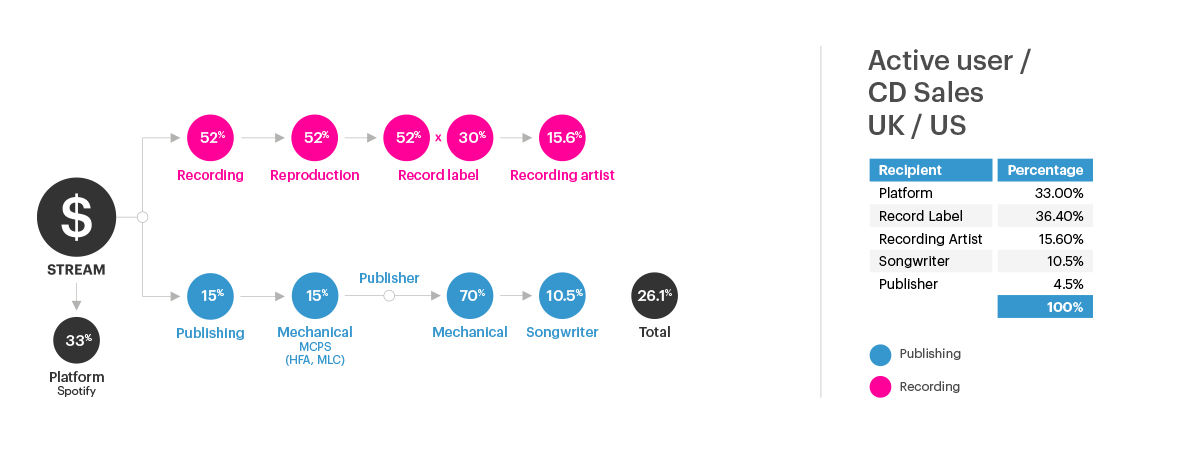

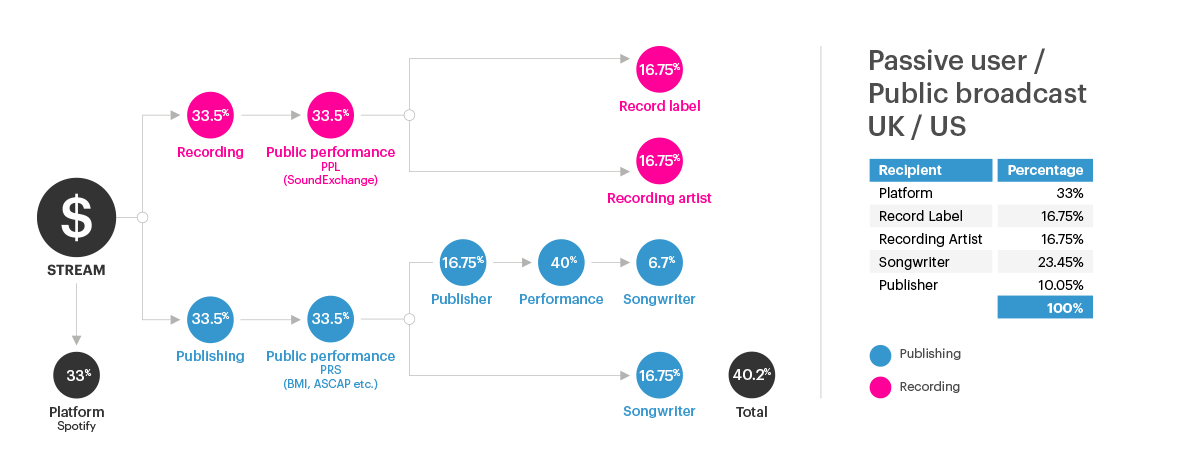

Several companies and studies have outlined how different remuneration methods for music streaming could work. Accountancy firm CC Young & Co offer some fascinating illustrations of different models, including equitable remuneration and an active/passive consumption model, which would distinguish between an active choice of the user or a passive algorithm determined by Spotify.

Source: CC Young & Co

Source: CC Young & Co

Source: CC Young & Co

There are also calls to increase the average cost of a streaming subscription as one way to increase the flow of money to artists. Will Page considered this in his article on what he called “Malbeconomics” – looking at why certain products (in this case wine) can increase in price over the years while others (like subscription streaming) do not.

How much any increase in streaming prices would materially change things for songwriters is unclear, with counter arguments being that a price increase would drive up ARPU but might see many people cancel their subscriptions and shift to the free tier of services like Spotify and YouTube, thereby reducing their personal ARPU.

As it stands, the main DSPs are fighting each other for market share and all regard price increases as a highly risky strategy. The stalemate continues.

While this is all happening in the background, publishers and songwriters continue to lobby and speak out about the imbalances they regard as affecting not only their income but also the environment in which new generations of songwriters have to step into as they try to build a career.

Alongside the #BrokenRecord drive are a multitude of others campaigns, among them #PaySongwriters, The Pact and Credits Due. This groundswell of activity and lobbying is affecting change and shows no sign of slowing down. The scale of the lobbying here is unprecedented and those behind the campaigns are not likely to back down easily or sell themselves short.

There is still a lot to fight for there. Spotify, for example, updated its Loud & Clear website and analysis tool this year. The intention was to show how streaming was a catalyst for whole new creator classes. And while certain songwriters are benefitting here, the reality for many others is far from rosy. Indeed, a Music Business Worldwide analysis of the data on Loud & Clear found that around 80% of artists on Spotify have fewer than 50 monthly listeners.

With upwards of 60,000 new tracks being uploaded a day to Spotify a day (although industry sources claim that this is now more likely to be 70,000), standing out has never been harder. If standing out is nigh on impossible, so too is any chance of making a living.

“It’s harder than ever for it to break through the clutter, just because there’s so much of it,” says David Israelite, President and CEO of the National Music Publishers’ Association. “You have this odd situation where the people at the very top of the food chain are doing well. There’s a lot of money to be made at the top. And there’s a much longer tail of people that make something from their music. It may not be a living, but you have a hugely bigger number of people that are able to make something from their music. It is the working middle class of professional songwriters or professional artists who can make their living from their music that is being squeezed.”

The plight and rights of songwriters has never been so high in the industry’s agenda. Change is happening, but a lot of work remains to be done.

3.2 Advocating for songwriters

A multitude of organizations who represent songwriters and publishers are lobbying hard for changes that will benefit those who create the songs the industry runs on. Among them are the National Music Publishers’ Association, the Association of Independent Music Publishers, the Music Publishers Association, the International Confederation of Music Publishers, the Independent Music Publishers Forum and The Ivors Academy.

Running alongside them are songwriter guilds such as the Nashville Songwriters Association International and the Songwriters of North America (as well as a new guild that Merck Mercuriadis of Hipgnosis Songs Fund is putting together).

Then there are the assorted artist and songwriter-led campaigning bodies like #BrokenRecord and #FixStreaming.

Issues high up the agenda for songwriters include writers being railroaded into giving up shares of publishing to people who have not contributed to the creation of a song.

This is, unfortunately, a common practice that stretches back to at least the 1950s where bullish managers would force songwriters to split publishing with their star act – even though their act was not a songwriter.

Writers are now pushing back against this with the formation of The Pact in 2021 that calls out artists who demand a cut of publishing for songs they did not write. Acts like Emily Warren, Ross Golan, Justin Tranter and Victoria Monet adding their name to a letter saying they “will not give publishing or songwriting credit to an artist who did not create or change the lyric or melody or otherwise contribute to the composition without a reasonably equivalent/meaningful exchange for all the writers on the song”.

There are also growing calls for labels to either stop refusing to give songwriters points on the master, or, if they do, taking those points out of the artist’s share rather than their own.

“The idea of not giving songwriters a point [on the masters] because it would be difficult, it’s just horseshit,” is Ross Golan’s forthright view on the matter. “It’s just lazy.”

Justin Tranter feels that major songwriters really should be adding their weight to the debate but politics or self interest are preventing them from doing so.

“I’m not saying that artists not taking their 5% or 10% is going to make it so they can retire – but when they’re already being robbed, being robbed more is too much,” Tranter says. “For a lot of the big songwriters, the reason they didn’t join [The Pact] is because they don’t want to. They’re selfish.”

Writers also feel that publishers should get more directly involved here to help them fight their corner with regard to label negotiations. This is something that Jin Jin (songwriter, founder of label/publishing/management company Jinsing and Senior A&R at Parlophone Records) feels needs to be addressed.

“I think that publishers should definitely be stepping in here and working in the interests of the writers,” she says of how to help writers to break the deadlocks that can happen here. “Individuals should not be having awkward conversations at the risk of ruining relationships.”

Beyond the points issue is the growing argument that songwriters are expected to do songwriting sessions for free – all on a promise that, should the song they work on gets recorded and released, they will share in the royalties. If the music is not used, however, they are out of pocket (for things like travel expenses) as well as having to give up time that they are not being paid for.

Tranter says, “Labels could give songwriters points or at least small fees, but the problem is that whenever that conversation comes up, it just comes out of the artist’s portion.”

Ross Golan argues there is an industry inertia here that means requests are going unheeded. “I’ve talked to so many presidents of labels saying something needs to happen,” he says. “A lot of them say yeah it does. And then nothing happens. I have certainly spoken to many executives about the idea of some sort of fee for songs that get released or held: if you’re going to hold the song forever, give us an annual fee of $4,550.”

These issues are now being raised repeatedly on social media through the #PaySongwriters hashtag as well as things like the March 2021 open letter from The 100 Percenters that, on behalf of songwriters, producers, artists and engineers, called on the heads of various industry organizations to “fully and fairly compensate everyone and not just yourselves”.

The European Composer & Songwriter Alliance has also directly raised the issue of points in its 2021 guidelines for songwriter fees and points. Among the many issues it covers, it argues for a development fee for songwriters for time spent working with artists, master points, a hold fee if a song is not used within a certain timeframe and fees to be associated with the use of stems from recording sessions.

The changing dynamics here were covered in a recent Billboard feature, showing how things are gathering momentum here.

Both individually and collectively a growing number of bodies, organizations, guilds and campaigning groups are demanding better terms, conditions and rates for songwriters.

Never has the voice of the songwriter been so amplified. Of course, things still have a long way to go, but the general momentum happening here and the headway being made is enormously encouraging.

Defending copyrights and advocating for fairer rates for songwriters is now part and parcel of a music publisher’s role. We can see this most obviously in the involvement of major and indie publishers in the CRB proceedings in the US as well as how publishers in the UK responded to the DCMS inquiry.

Even though there are lots of voices here all coming from slightly different positions, there is a need to identify areas of common interest and to then speak powerfully on them with one voice.

While this is helping to build a new and better tomorrow for songwriters and publishers, a recurring argument in our interviews was that issues from the music business’s past are at risk of holding back its future.

Björn Ulvaeus – songwriter, member of ABBA, co-founder of Session and President of CISAC – says, “Some things can be regulated with the help of a parliament, other things have to be adjusted and will be either through disruption or by a more evolutionary change. But, for instance, the division between label and publisher in the streaming world is a legacy from the olden days. It’s absurd and it will change.”

David Israelite argues, however, that regulation is one of the things that has historically held music publishers back and a lack of regulation has allowed the record labels to swoop in and take the lion’s share of streaming income.

“Record labels and artists are in a total free market,” he argues. “They negotiate their rates and prices. If they don’t like the deal, they don’t have to do it. As a result of that, they’re getting a fairly healthy share of the revenue, about 52% of revenues going to the sound recording side, split with labels and artists.”

He continues, “On the publishing side, unfortunately, we’re not in a free market. We’ve been regulated since 1909 because of player piano roll analysis. And today what that means is that a Spotify, an Apple or an Amazon, while they negotiate prices with a label, they don’t negotiate with music publishers and songwriters. Instead, we have this kind of antiquated process where we go to a trial, three judges set our prices that last for a five-year period and it’s a compulsory license.”

This is all a situation that Michelle Lewis (singer, songwriter, composer, and music creators’ rights advocate, as well as the co-founder of SONA (Songwriters of North America)) says is holding back the sector from driving real change.

“Songwriters have to work under all these outdated laws and regulations – some that date as far back as early as the 1900s,” she says. “There’s a brutal combination of antiquated copyright laws and 1940s consent decrees involving US antitrust law which prevent us from working in anything even close to a free or fair market. Plus, a 1980s National Labor Relations Board ruling prevents us from unionizing. So we’re hamstrung from taking any collective actions and doing much about them.”

Tiffany Red is artist, songwriter, producer and founder/Director of The 100 Percenters (a non-profit which advocates for better terms for songwriters and which recently received $100,000 from Sony Music Publishing for its Songwriter Stimulus Program and its Emergency Fund).

“I created the 100 Percenters to advocate and support all songwriters, producers, artists, and engineers focusing on marginalized creatives,” she explains. “Our mission is for all music creatives to have equitable access to opportunities, education, support, and revenue streams.”

Red does not hold back in her criticisms of the problems that persist here and the historic reasons things are so imbalanced.

“The amount of money the sound recording makes compared to publishing is criminal,” she says. “The DSPs and record labels need to pay more to songwriters. That’s just the bottom line. Our royalty rates need to be higher and record labels have to stop keeping most of the revenue or the songwriting profession will disappear. The fact that songwriters are still bound by the copyright act of 1909 while the record labels and DSPs are in a free market is despicable. We deserve to be free to negotiate our rates just like them.”

The legacy issues are causing endless roadblocks for publishers and the frustration that they continue to experience is palpable.

“Our negotiations with the digital services are never straightforward and we have to keep pushing to improve the payments that we can make to our songwriters,” says Antony Bebawi, President of Global Digital at Sony Music Publishing. “The biggest challenge that I see right now is the fact that we can’t have a sensible negotiation with a lot of the services in the US. The licensing system in that market is very complex, and it is consistently used by the services to try and reduce the amounts of money that they pay to songwriters. And to try to reduce it to a level that’s below what’s being achieved in free market negotiations outside of the US.”

He cautions that this should not be seen as an issue specific to the US but rather approached as one that has enormous global repercussions and implications.

“What happens in the US doesn’t just affect US songwriters,” insists Bebawi, “it affects songwriters around the world.”

Hipgnosis founder Merck Mercuriadis is moving to create a new songwriting guild in the US that is said to be similar to “Hollywood’s Writers Guild of America”.

Mercuriadis tells Synchtank that the guild is planned to launch this summer. Outlining how it will work, he says, “The plan with the Guild is really simple – that no negotiation takes place going forward that affects how a songwriter is paid without songwriters at the table from this guild […] What we want from this guild is to have a consensus view of the entire songwriting community and for that consensus view to be represented by songwriters.”

Michelle Lewis is not convinced this will be as egalitarian as it should be due to the class system among songwriters.

“I am skeptical about songwriters at these levels, at the point in their careers where they would sell off their catalogs, becoming activists,” she says. “I don’t see the biggest writers becoming particularly vocal on the issues that affect the [smaller] writers.”

Ross Golan agrees that the emergence of a streaming-created class system in songwriting might see powerful voices step back from the debate, partly out of self-interest.

“Most of the loudest voices in the advocacy world for songwriters are not the most competitive songwriters,” he says. “We have opportunities as a generation to actually be part of the bigger conversation. What scares me is that even if there was a union, I don’t know that the strongest writers in the world would join it. Even when we tried with The Pact, it fell apart pretty quick once there was pushback from the artists who are taking the publishing. Rather than the writers standing up for each other, they kind of cowered because they didn’t want to lose the cuts.”

There is still, however, an education process that has to take place here with some songwriters so they remain abreast of all the developments and understand the importance of the current lobbying and the pushes for better deal terms.

“Artists are more savvy,” suggests Tim Parry, CEO of Big Life Management, “but less interested in the details.”

Jon Platt, Chairman and CEO of Sony Music Publishing, says the onus needs to be on the publishers to bring their writers up to speed on all the issues du jour.

“We communicate with our songwriters and composers on a regular basis. For example, before the end of the year, we shared an update about the current CRB negotiations in the US. It was well received and appreciated by our songwriters.”

He adds, “Some of the ways that we’ve focused on education is through music publishing workshops that we’ve done here for songwriters. We’re also starting an onboarding process for newly signed songwriters; showing them how things operate and where to go when they need assistance. These are just some of the proactive approaches that we’re taking here at Sony Music Publishing.”

Ross Golan feels there is a pressing need for songwriters to educate themselves about the commercial realities of operating in the modern music business, especially with regard to how songwriting models are changing creatively and how that will affect them commercially.

“I think it’s the responsibility of executives to teach writers about the business,” he says. “I think it’s the manager’s job. I think a publisher has to communicate with the managers, but, more importantly, songwriters need to take some ownership. […] They don’t care to learn about their own business. So, you’re in this place where they don’t mind being one of seven writers on multiple songs, but at 14.28% of a song.”

Mike Smith, Global President of Downtown Music Services, says that his company marks a break from the old model where ownership of the copyright was paramount. This means that writers will only assign their works on a limited basis and with more favorable terms, meaning the “use it or lose it” clause becomes increasingly redundant.

“I feel the person who owns the copyright should be the person who wrote the copyright,” he says. “Obviously music publishing has traditionally been all about owning copyright – and I’m excited that we’re in a position to move away from that. What we’re trying to do as much as possible is see if we can bring that split down even further so that the writer gets their copyrights back as quickly as possible.”

Singer and songwriter Jin Jin also feels that song ownership is critical for songwriters.

“In terms of the future, ownership of songs is important to a songwriter,” she says. “This is our pension in the long term and what we have worked tirelessly for. Our intellectual property is pretty much all we have, you know!.”

While there is a lot of talk about the need to empower songwriters, not all songwriters feel that any such empowerment has fully materialized yet.

“I think you are more empowered to do what you want, but the range of outcomes that your actions can do are potentially still quite reduced,” is the dry summation of Adam Betts (drummer, teacher, producer, and songwriter). “I think you can be empowered to do whatever you want, absolutely, which is really cool. But how much of that is actually going to have an impact is debatable.”

For Justin Tranter – Grammy Award-nominated songwriter and producer, founder of Facet, activist and GLAAD Board member – the picture is even bleaker as they believe that songwriters have been intentionally shunted away from the center of the debate so have decreasing say in the matters that affect them most.

“Everything is built to keep the songwriter down, because we are the most powerful piece of the equation,” they argue. “And so, like all systems of power, you try to keep the most dangerous people down.”

3.3 Transparency and data

As a headline, it was always going to grab attention.

“Abba’s Björn Ulvaeus launches campaign to fix £500m music royalty problem,” proclaimed a feature on the BBC site in September 2021. It was related to the Credits Due scheme seeking to have more robust data covering who wrote and played on a track – as well as who should get what share (where ultimately the ISWC is assigned much earlier in the songwriting process and long before any recordings are released).

Credits Due is focused on fixing broken metadata around compositions and recordings and ensuring that the legacy issues of the past are not repeated in the future. Without the correct metadata, those who are to be paid will not get all the money that they are owed. Indeed one of the key recommendations arising out of the DCMS inquiry into the economics of streaming was that there should be the development of minimum data standards to ensure these numerous metadata holes are closed off.

“One thing that the regulator could demand is that nothing enters the system without correct identifiers needed for the future payments,” Björn Ulvaeus tells Synchtank. “That’s something that actually could happen. And if that would happen in Britain, that you cannot release without having that data, that would change a lot.”

As a story, it gets straight to the heart of the industry debates around data and transparency. It sometimes feels like the more data there is in the streaming age, the less transparent it becomes.

There are both technological issues (the correct credits not being properly ingested, meaning an inherently flawed payment flow) and institutional issues (artists and writers not being given the full picture) at play across these twin issues of data and transparency.

As covered extensively in our Drowning In Data report, there is a pressing need for publishing data to be harmonized. Publishers need to use technology to bring through better data and rights management practices.

System interoperability is critical here so that accurate data is shared through the ecosystem and the reporting problems that have dogged the business start to become a thing of the past.

Indeed, Ulvaeus is calling for a single database, something the DCMS argued for, to solve many of these recurring problems in the sector. PRS for Music attempted this over a decade ago, but the Global Repertoire Database proved disastrous at the time, falling apart in 2014. In the US, however, the Mechanical Licensing Collective (arising out of the Music Modernization Act being signed into law in 2018) began tackling this in early 2021.

“There ought to be one world music database, a public one where everyone can see who’s written the song,” says Ulvaeus. He adds glumly that the road of history is littered with failed attempts by CMOs to achieve this utopian database. “They have tended, historically, to invent the wheel every time and do it badly.”

He says technology is key to this but also a generation shift – and a shift in the demands of new songwriters to fix these legacy problems – is needed to pull the whole sector out of this rut.

“I think everyone has to realize that there needs to be much more transparency and efficiency in the system,” he proposes. “And young people, be they publishers, writers, whatever they are, they should demand from the old guard that they don’t be stumbling blocks. It’s going to happen anyway. We need to let this metadata out and we need to be more transparent with it. Otherwise you’ll become totally irrelevant.”

The arrival of the Mechanical Licensing Collective is seen as a landmark moment for the industry, even though it is still at a nascent stage.

“I think that was almost like a coup in its transparency, in its result,” says Michelle Lewis. “We got transparency in a way that we didn’t even know we were going to get transparency.”

There are technological responses to these metadata issues, helping to avoid the pitfalls of the past. Session (previously known as Auddly), for example, was set up by Swedish songwriter and producer Niclas Molinder and has backing from both Björn Ulvaeus and songwriter Max Martin

It aims to fix the data gap and also help tackle the issue that creators have here with not wanting to discuss splits (out of fear or awkwardness), helping them to fully understand the significance of data.

“It’s hard for the songwriters and the creators to understand the complex world of music rights, and it’s hard to keep track of all the identifiers,” says Molinder. “Many times today, a music creator is both a songwriter and a performer. So, as an individual, you have an IPI as a songwriter, you have an IPN as a performer. In some territories if there’s not an IPN you have an ISNI.”

He adds, “I understand that the creators shut down – it’s too much, it’s hard to understand. So we should use technology to verify the identity of all of the creators. That to me is [issue] number one. Number two is to capture the data as early as possible. We ask them too late in the process. So, if we can do that together, then all the brilliant technology and databases internally in companies or internally in societies will be much more efficient if we feed them with the right data. It doesn’t matter if you have a modern database; if you feed it with the wrong source information, it will still be wrong.”

Helienne Lindvall says the reticence among songwriters to raise this issue in songwriting sessions is real.

“A lot of songwriters don’t want to discuss splits in the studio – I understand that,” she says. “I compare it to giving someone a prenup on the first date – it kind of takes the creative ‘romance’ out of the session. And then it ends up getting discussed in numerous email threads instead, which then in itself can result in conflicting registrations. Hubs like Session and other such hubs, where at least there is some transparency in what happens to a song down the line, are really helping to solve this problem. I’ve done quite a few EDM records, and a lot of the time the song disappears out of the studio and suddenly there’s two or three more people on the track and on the credits, without the original writers being properly consulted. This is an issue across the board with records getting released without any of that being agreed – and sometimes released without our knowledge.”

PROs also need to adopt new technologies and modernize their processes in order to enable them to make bigger and bolder leaps in their digital licensing to help the entire sector.

As Molly Neuman, President of Songtrust puts it, ”The people that we register works with might not have the capacity to receive the complete data picture that we can share with them. This is sometimes something that I struggle with understanding; but, at the same time, I do understand that we’re working with societies and collective management organizations that are hundreds of years old and we know they are investing in improvements. We know that they’re investing in a better management of the scale of rights that now is a part of our daily lives. But we are not all operating with the same system of standards, application of standards, ability to process, ability to attribute, and the dysfunction and that inconsistency is really what we’re maintaining and what we’re operating with.”

David Israelite adds, “Performance, at least in the US, is just over 50% of the revenue. So it’s the number one source of revenue. And yet, if you look at the type of transparency that exists from your PROs compared to the type of transparency that exists from your publisher, I think there’s a gap there. Not only can you audit your publisher, which you generally don’t have audit rights for your PRO, but I think that in the performance world, there’s really a lot of information that needs to be made more transparent, more digestible, even just in terms of where the money’s coming from.”

Auditing remains a contentious issue in the industry. While no PRO is auditable, publishers are – but this comes with a number of caveats. Even if songwriters audit their publishers, they will never have a full picture of what is happening because they can effectively only audit what a publisher has received or has chased, but the source of this income does not necessarily share how these payments are made up and what has not been paid.

Graham Davies, CEO of The Ivors Academy, agrees that headway is being made here, but argues there is still some distance to go.

“There is still a lot more transparency and efficiency to be achieved by PROs,” he proposes. “We have been working with the MMF for a number of years lobbying for greater access to information to track international payments and deductions.”

Kobalt Music founder Willard Ahdritz says that proper and regular auditing of accounts and payments is one major part of the solution here.

“Both Kobalt and our clients have audit rights on AMRA,” he says. “AMRA has created the first global transparency in the digital arena. We have managed to create this because of our market share and working closely with the DSPs such as Spotify, YouTube and Apple.”

In the background of all of this is the issue of a knowledge gap within the songwriting community. It was a recurring motif in interviews for this report – where it was felt songwriters are dangerously uninformed about critical parts of the business and how this will affect them.

“Songwriters are so generally uneducated on their sources of income,” says Michelle Lewis, songwriter & Co-Founder of SONA.

Helienne Lindvall concurs. “So many songwriters and sometimes even managers don’t realize how royalties are paid out – on what basis they’re paid,” she says.

Emerging singer and songwriter Josh Oliver (aka Jolé) admits that there are gaps in his knowledge about the way the industry works.

“I still don’t fully understand the mechanics of it all,” he says. “All the different departments, their roles, nuances of territories, it’s almost too much for the brain sometimes. I just kind of leave it in the hands of people I trust and who know what they’re doing to chase stuff for me.”

He adds, “I’m not sure whose responsibility it is to educate songwriters, but at least I know who [e.g. my publisher, manager, network] to ask if I have questions. There are songwriters out there who don’t even know what questions to ask, let alone who to ask for answers.”

Improving streaming rates for songwriters is a long-term goal, but better efficiencies in the systems around the industry must be achieved in the interim.

Black box money is still an issue, with huge sums of money still not finding their way to the right people swiftly.

In February 2021, for example, the MLC announced it had collected just over $424 million in accrued historical unmatched royalties from DSPs in the US while last year The Ivors Academy in the UK estimated that at least £500 million a year is being “delayed, unallocated and/or mis-allocated to songs that have already received payment”. These are not insignificant figures.

Helienne Lindvall says there is entrenched thinking and behavior in the industry that is precasting that money from being properly, and rightly, shared.

“As long as we have a black box that then gets distributed according to market share, for some of the biggest players there’s no incentive to fix it,” she proposes. “It’s almost an incentive to not fix it because for them it’s like getting paid twice. As a lawyer once told me: the only thing the majors fear more than piracy is accuracy.”

These are legacy problems that persist rather than get fixed. The onus is on everyone here to make the structural and software investments to consign this problem to the dustbin of history.

Related to all this is the speed of payments, shifting from annual payments to quarterly payments to monthly payments. “I see a future when there’s no reason why you wouldn’t be paid in real time,” says Björn Ulvaeus.

David Israelite does warn, however, that transparency can, in the modern digital music business, be equal parts pro and con.

“The MLC has been leading the way in providing [greater] transparency,” he says. “I think that it’s a little bit of a double edged sword in that there is so much information now that you can overwhelm people with your transparency. It’s easy for people to ask for transparency. And then the question is: what do they do with it?”

Rupert Skellett, at Beggars Group, concurs with this point about data overload being an equal – if different – problem to data scarcity or data opaqueness.

“A lot of the transparency discussion does center around not having certain data, but there is also the problem that there is so much data that there is inevitably going to be a selection process of that data and the organizing of it,” he says. “And that’s not necessarily a signifier of something nefarious on a publisher or collection society’s part. It’s just trying to get the data into something that’s comprehensible to writers and artists.”

Some of those working in this space will insist that such transparency can materially affect the careers and earnings of songwriters if handled properly.

“We are fortunate that we do have some visibility into the spectrum of earnings and what it takes, and I think that’s exciting for me to be able to help move different segments or groups of creators into different earnings bands – and what that could actually mean in terms of changing lives,” says Molly Neuman of how Songtrust is set up.

“What I’m hoping for, through the work that we do and the next phase of Songtrust, is that we are really actively and intentionally supporting revenue improvement for our clients and our client class,” she says. “I think if we think about the stages of progress that we can make, one is harmonizing data so that, even if the current allocations and calculations are not ideal, that under the current standard everybody’s getting what they’re earning. That’s the foundational state that Songtrust can absolutely participate in – and does. And next is a progressive advocacy for a more balanced, more equitable distribution of whatever the current pie is towards the reality of how the industry is evolving.”

The Music Managers’ Forum in the UK addressed the twin issues of transparency and payments in early May 2022 with its Song Royalties Manifesto. The three key points it wants addressed are:

- the establishment of a public database of every new ISWC (which is logged before any track is released, with CISAC updating its ISWC system in 2020 and saying it “has led to tighter integration in the assignment of ISWCs by member societies over the last three years”), effectively working as a global version of the MLC in the US;

- a requirement for labels and distributors to provide ISWCs within the metadata for every track they want added to DSPs (and they risk the tracks being rejected and themselves being downlinked by the DSP if the ISWC is incorrect;

- publishers and collecting societies to deliver their own data feeds to the above-mentioned public database that lists every work they have an interest in.

“Songwriters and composers are being failed by outmoded processes that drastically delay and reduce their streaming royalties,” said MMF CEO Annabella Coldrick on the launch of the manifesto. “Each year, obscene amounts of money are being lost or mis-allocated.”

This MMF move was followed up later that same month by German collection society GEMA when it unveiled its own manifesto where it outlined 11 points “for more fairness, transparency and sustainability in the music streaming market”. Key focus points include addressing “the partially non-transparent payment streams” around streaming as well as better data and transparency across the entire streaming ecosystem, from payments to playlisting policies.

The biggest burning issue around transparency is not about getting access to billions of lines of micropayments from a multitude of digital platforms, but rather letting daylight in on the deal terms certain content owners have signed with those digital platforms.

“The recorded music company goes in and negotiates with Spotify or Apple, and it does so under an NDA so that it doesn’t have to disclose the terms that it’s agreed with that company,” says Merck Mercuriadis. “You don’t know what they’ve agreed and what price the songwriter is ultimately paying for it.

This, he feels, is one of the biggest problems facing songwriters today. In one part of the business, deals are being done that directly affect the earnings of songwriters, but they are not permitted to get any insight into what those deals are.

“I understand why NDAs exist, because there’s commercially sensitive information and you don’t necessarily want everyone knowing your business – but you can’t tell me that every artist and every songwriter that’s associated with those companies doesn’t have a right to know how they’re getting paid,” he insists. “A songwriter doesn’t know because a record company and a publishing company can’t explain to them, based on the deals with the DSPs, what their rate of pay is.”

As Niclas Molinder, songwriter, producer and founder of Session, succinctly puts it, “The PRO that I’m registered with has signed an NDA with a streaming service so they can’t tell me how much money I get. That’s not fair.”

Graham Davies of The Ivors Academy also states that NDAs are badly obfuscating things with regard to streaming services. “There are transparency issues about the relationships between major groups and the DSPs,” he says. “For example: what is the relationship between the majors and Spotify and are there preferential deals for placement on playlists? How are the algorithms constructed, how do they work, who monitors them? So, I think there is quite a lot to be done on transparency.”

3.4 Values-based industry

Slowly but surely, a new “values-based” industry is emerging where music companies are pledging to reexamine industry practices and do right by creators, designed to instill a more egalitarian culture where both creators and businesses can thrive.

Fairer contracts are starting to emerge where archaic clauses are being scrubbed out. Chief among them is the steady elimination of the “minimum delivery release commitment” (MDRC), wherein songwriters had quotas imposed on them to have a set number of songs commercially released within a particular time frame.

“Acknowledging that MDRC deals are archaic is a significant first step in the modernization of a music industry that has long needed to participate in its own evolution,” artist and songwriter Tiffany Red told Variety in July 2021.

Contracts are also being revised and redrafted with the implications of the streaming age in mind.

Writers will still argue these revisions are not happening quickly enough or applying broadly enough, but change is afoot.

Alongside these wider contractual changes, a new generation of companies, platforms and services are coming through with a renewed emphasis on egalitarianism and taking the core philosophies of transparency and fairness to create a new type of music business.

Kobalt was arguably the first to take a different approach and force others to bend towards its underlying philosophy.

It can also be seen in the rise of companies like BMG.

“The biggest threat for us – and it’s not fatal – is if the other guys become good, fair and transparent,” BMG CEO Hartwig Masuch told Rolling Stone last year. “A lot of what we do becomes not as exclusive at that point. The moment the market leader decides ‘we want to be the good guys; We’re rich and now we want to be loved,’ then we have to really think about how do we keep any competitive edge.”

Following the lead of Beggars Group in 2016, the major labels started to, in certain instances, wipe unrecouped balances for recording artists in order to begin paying through streaming royalties. The fact this came after the majors were heavily criticized in the DCMS inquiry is surely no coincidence.

In July 2021, Sony Music Publishing became the first major to move here by opening up the Legacy Unrecouped Balance Programme to qualifying songwriters. “With historic policy changes across our business, we are taking important steps toward creating a more equitable, transparent music industry for songwriters and all creators,” said Jon Platt in a staff memo (that was subsequently republished by Music Week).

When we spoke to Jon Platt he said, “The Legacy Unrecouped Balance Program is an important effort to improve the lives of songwriters. We’ve been very pleased with the responses that we’ve received from songwriters and composers, who shared that many of them are now able to participate in today’s music business. I am also grateful for the response we have received from successful songwriters for whom this program doesn’t apply, yet who are very happy that other songwriters are able to participate in today’s business. Our goal is to make the lives of all songwriters and composers better.”

Warner Music made its move here in February 2022 wiping unrecouped balances for artists and songwriters under certain circumstances (i.e. “artists and songwriters who signed to us before 2000 and didn’t receive an advance during or after 2000”) while Universal Music Group took similar steps in March 2022 (for “eligible creators and their immediate heirs who have not received any payments since January 1, 2000”).

Crispin Hunt, while he was still chair of Ivors Academy, spoke to BMG for its blog and was asked why the industry was getting so much criticism.

“The music industry is a wonderful thing, but it needs to realize it’s there to serve the needs of artists and songwriters,” he said. “They are not there to keep music companies in business. We live in a world in which top music executives seem to benefit disproportionately while the people who create the music often struggle to make a living. The song in particular is criminally undervalued.”

The industry as a whole is, according to Andy Heath, of Beggars Group and co-founder of UK Music, facing a crisis of trust and needs to move swiftly and decisively to address it before it is too late.

In an op-ed for Music Ally in March 2022, he wrote, “Transparency is key: record companies must be more open about royalty flows, and tech companies must be more open about the opaque algorithms that determine promotion and recommended tracks.”

There is also a greater push across the industry as a whole to foster greater diversity across writers signed by publishers as well as the staff working inside publishing companies and other industry organizations.

A multitude of companies have stepped forward by appointing executives, groups and boards tasked with having a more diverse – and therefore more representative – professional and artistic community.

UK Music’s Diversity Report 2020 was a significant development, putting precise figures on representation across the industry and spotlighting where change still needs to happen. It followed this up in 2021 with its 10-point plan, developed by the UK Music Diversity Taskforce, to address diversity and bring about real change.

“It was clear that there was nobody who looked like me or represented my particular creative writing style,” says Jin Jin about why she stood to be a member of the Board of Directors at The Ivors Academy. “I think it has always been harder for us Black women, although it appears to be slowly moving in the right direction, where Black female leadership is viewed as crucial for change. In LA, you definitely see a few more female execs, and people of color in the industry, and it’s good to see that. Representation is crucial in all aspects of life. We now appear to be gradually moving to a place where the industry is more talent focussed and hopefully this will continue.”

Having more voices to talk about these issues of representation will be catalysts for the change so many desire, taking an inequitable situation and driving significant improvements.

“I still see women, particularly Black women, having their work undervalued,” says Shauni Caballero, Founder of The Go 2 Agency. “However, I do feel a stronger sense of community amongst women within the music industry. We are collectively coming together to educate and support each other.”

Tiffany Red says that she rarely saw anyone who looked like her in leadership positions in the music industry – or any other industry – and this was a motivating force behind her setting up The 100 Percenters.

“Unfortunately, I don’t have the same negotiation power as my white male counterparts,” she says of the challenges she faced over the years as she progressed through the music business. “I have to prove myself in a way they do not. It’s incredibly frustrating. I’m confident I’d have more support and funding for The 100 Percenters to help songwriters in need if I were a white man.”

She adds, “I would like to see publishing companies support all their writers, not just the 1%ers. All of the companies that pledged hundreds of millions to social justice initiatives, I challenge those companies to give some of that money to BIPOC and marginalized songwriters. They need it. The 100 Percenters would be more than happy to help distribute those funds.”

The work of The 100 Percenters parallels the Black Empowerment Thru Music initiative (set up by The Royalty Network).

In its official statement it says, “The Black Empowerment Thru Music initiative was created in the wake of the social unrest following the killing of George Floyd, its roots can actually be traced much further: to the very foundation of the company. The Black Empowerment Thru Music initiative offers aspiring songwriters, artists and entrepreneurs everything from music education to studio time, free instruments, career opportunities, and financial support in the service of opportunities for the Black and Latin communities.”

Lawson Higgins, Vice President of Creative, explains further about the initiative: “I think the most valuable thing we did [was that] we mentored individuals for a long period of time over the pandemic and assisted them in their music and their writing and what they wanted to do.”

The Annenberg Inclusion Initiative says that change is happening here. Things might not be perfect, but shifting cultural attitudes and growing lobbying (alongside more proactive initiatives) are having a positive impact.

“Since beginning to measure the percentage of women songwriters working on songs in the Billboard Hot 100 Year End Charts, we have seen slight progress for women,” it says. “From 2017 to 2019, the percentage increased from 11.6% to 14.4%. While not significant, this is a sign that there may be greater opportunities for women songwriters of popular music. The percentage rebounded to 12.9% in 2020 which indicates that these gains are difficult to sustain. We did, however, see growth for women songwriting nominees at the Grammy Awards. In 2017, women comprised 14.3% of nominees whereas in 2021 this was 44.8%. Additional research is needed to understand whether women songwriters have made progress in specific genres, or in working with both major and independent publishers.”

She Is The Music, a non-profit set up to increase the number of women working in music, has played a key role here by launching a number of all-female songwriting camps that have directly resulted in female writers getting credits on tracks such as ‘Call Me’ by Rozes, ‘Love Runs Out’ by Martin Garrix (featuring G-Eazy and Sasha Alex Sloan), and a track on Alicia Keys’ most recent album, Keys.

“Our camps give participants the opportunity to create music and collaborate in a room full of other female producers, engineers, and writers,” says Michelle Arkuski, Executive Director of She Is The Music. “The most common feedback we receive is how comfortable and refreshing it is to write with and meet other women that may not have otherwise been able to connect. Bringing women together in the studio is a profound starting point to future diversity of songwriters and inclusion of women in the studio.

Alongside having more people from different ethnic backgrounds and more females in higher positions, there is a need to have more LGTBQ+ representation in companies and across the songwriting community.

“I do think we have to celebrate the small growth and the small changes while still fighting for more,” says Justin Tranter, Grammy Award-nominated songwriter and producer, founder of Facet, activist and GLAAD Board member. “Young people are moving so fucking quickly, there’s no stopping them and it’s amazing.”

They are firm in their belief that changes at the executive level will drive changes in terms of the types of artists who are signed to deals.

“I think a big thing is that the publishers in charge should be hiring more LGBTQ+ publishers,” suggests Tranter. “That would solve a lot of the problems. We need more LGBTQ+ executives.”

They continue, “We [queer people] are the tastemakers for the dance side of pop and a lot of the alternative side of pop. It is our community. So, the fact that there aren’t CEOs desperate to find LGBTQ+ publishers who understand what that community wants is really bad business. It’s bad for humanity, but it’s also bad business.”

Jon Platt of Sony Music Publishing says diversity is a priority issue within Sony Music Publishing and that he and the company are making important strides forward here.

“The songwriter and artist community is diverse, and that creative diversity has been a huge benefit to the music industry,” he says. “As I’ve always said, the music companies should be as diverse as the music we represent. I’m very proud of being intentional about a culture of diversity, equity and inclusion here at Sony Music Publishing. It is important that we are intentional in our support of diversity in all of its forms – whether it’s our Black and brown employees, the LGBTQ+ community, working parents, the AAPI community and more, this is something we must achieve.”

He continues, “We’re building that culture. It’s important that we support our songwriters and it’s important we support our people who work with us internally. Sony has been very supportive of what we’re doing and what we want to do going forward, particularly in these times. When you speak about inclusivity, the work should never stop. The diversity of the music will never stop. So, our need for progress will never stop. It’s about doing the right thing. It’s common sense at the end of the day, and I’m very proud that we have the support of Sony. We are aligned and moving forward together.”

There is a major seachange happening across the industry and a multitude of issues – that were previously ignored or badly underserved – are being prioritized.

“Mental health is very important to me,” says Mike Smith of Downtown Music Services. “Diversity, inclusivity, and equality, again, just common sense. I mean, you can talk about it’s fair, it’s good to offer opportunity. To me it’s just plain business sense. “I’m very proud that within Downtown Music Services, the majority of the senior managers are women. Admittedly, I’m a middle-aged white guy running our business, but I feel very confident that the person that takes over from me probably won’t look so much like me. And I think that’s a good thing.”

He continues, “We’ve got a long way to go, I think, on diversity, particularly in terms of ethnicity, but we are addressing this and doing everything we can to improve that. And I think the more that we do that, the better a business we will become. I look at the people that are listening to the music that we are involved in the creation of, and I want our workforce to look like those people. I feel confident we’re on our way there.”

Tayla Parx – singer-songwriter, actor, entrepreneur and founder of Burnout – concurs, arguing that a new generation of music companies is coming through that will take as ready everything that, until recently, was, at best, paid lip service to or, at worst, swept under the carpet.

“That’s the beauty of where we are in the music industry,” she says. “We have all these newer companies starting off with these once taboo things as priorities, and the massive publishing companies are also starting to catch on. We can build that now with a bold enough vision and people willing to take a leap of faith.”

Michelle Lewis closes by saying that the most fundamental shift is that the old relationships – based on a power imbalance between writers and publishers (and the industry as a whole) – have been recalibrated to be much more egalitarian. What were uneven relationships are now becoming truly equal partnerships.

“I feel like there has been an evolution in the writer/publisher relationship,” she concludes. “Ideally, we’re no longer seen by a publisher as their ‘charge’ or their little song machine, but as a partner. We’re in this together: we consult, we strategize, we look at opportunities and we approach them together like business partners. The best [publishers] take a holistic view of the writers they work with – by valuing the work of songwriting, rather than just the result, and by not conflating the songwriter with the songs they create.”

Stay tuned for part four, Digital Drivers of Growth, which will examine existing and emerging income streams, and how music publishers can capitalize on new opportunities.

Subscribe to our newsletter to recieve the next instalments of the report in your inbox each week.

With huge thanks to the following report contributors:

Adam Betts (Colossal Squid), Antony Bebawi (Sony Music Publishing), Björn Ulvaeus (ABBA, Session, CISAC), Brontë Jane (Third Side Music), Carianne Marshall (Warner Chappell Music), Carter Armstrong (peermusic), Chris Cass (Synchtank), Colin Young (C.C. Young & Co.), Craig Currier (peermusic), David Israelite (National Music Publishers Association), Golnar Khosrowshahi (Reservoir Media Management), Graham Davies (The Ivors Academy), Guy Moot (Warner Chappell Music), Helienne Lindvall (European Composer & Songwriter Alliance), Janet Kirker (Synchtank), Jin Jin, John Vella (Tenderfoot), Jon Platt (Sony Music Publishing), Josh Oliver (Jolé), Justin Tranter, Larry Mestel (Primary Wave Music), Lauren Faith, Lawson Higgins (The Royalty Network), Marc Cimino (Universal Music Publishing Group), Mark Mulligan (MIDiA Research), Mary Megan Peer (peermusic), Merck Mercuriadis (Hipgnosis), Michelle Arkuski (She Is The Music), Michelle Lewis (SONA), Mike Smith (Downtown Music Services), Milo Evans, Molly Neuman (Songtrust), Nancy Matalon (Spirit Music Group), Niclas Molinder (Session), Nile Rodgers, Rob Dippold (Primary Wave Music), Ross Golan, Rupert Skellett (Beggars), Sara Lord (Concord Music Publishing), Shauni Caballero (The Go 2 Agency), Stephen Duval (Empowerment IP Capital), Tayla Parx, Tiffany Red (The 100 Percenters), Tim Parry (Big Life Management), Tom Weller (Ditto), Tricky Stewart, Vickie Nauman (CrossBorderWorks), Willard Ahdritz (Kobalt Music Group)

4 comments

[…] facing songwriters today. In 2022, it’s rare for a big hit to be the product of a single person. Song-writing teams are the norm, with areas of composition ever-more compartmentalised. This means multiple lyricists, beat-makers […]

[…] facing songwriters today. In 2022, it’s rare for a big hit to be the product of a single person. Song-writing teams are the norm, with areas of composition ever-more compartmentalised. This means multiple lyricists, beat-makers […]

[…] facing songwriters today. In 2022, it’s rare for a big hit to be the product of a single person. Song-writing teams are the norm, with areas of composition ever-more compartmentalised. This means multiple lyricists, beat-makers […]

[…] facing songwriters today. In 2022, it’s rare for a big hit to be the product of a single person. Song-writing teams are the norm, with areas of composition ever-more compartmentalised. This means multiple lyricists, beat-makers […]