Entertainment industry veteran Tarquin Gotch chats to us about his time in A&R, working with the brilliant John Hughes on films like Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, managing AC/DC’s Brian Johnson, and more.

Hi Tarquin, thanks so much for joining us today. Can you tell us a bit about how you first got into the industry?

What was it like doing A&R back then?

It was a nice time to be doing A&R because music was the centre of our culture in a way that it no longer is. Music has moved to the periphery, and technology and tech is at the centre now. So it felt then as if it had a cultural importance, and that was quite gratifying. Spotting talent is not difficult, you all do it whenever you go to a festival and you go, “Oh, I like that group.” But finding talent that really wants to work hard and that isn’t going to self-sabotage is the tricky part. And of course there’s no way of really knowing that, you just have to sign people and work with them. The huge stars like Bono, Sting, Elton John have a work ethic that is extraordinary. That’s what separates them – it’s not the only the talent, it’s also the work ethic.

How do you think today’s A&R compares?

Well, you mentioned Clive Davis and working with him at Arista Records was a great education for me. You could sign left field things as long as the artists themselves were willing to come into the mainstream. It was exciting going out in my day to look for really exciting artists and then over the course of a career move them from the cultural periphery into the mainstream. Now the record labels and the A&R people don’t have that luxury, they have to deliver mainstream straightaway. They have to hit the ball out of the park in order to make money. This is true of the film business also. You have to find something that will appeal to an incredibly large number of people – that’s a very wide demographic and it means that you tend to make slightly bland mass-appeal stuff.

Labels can’t afford to develop the artists, so they get a team together to try and guarantee a hit straight from the get-go. And if you don’t have some measure of success immediately you find yourself whizzing out of the exit from the major labels. It’s just a fact of life, that’s what it’s like. There’s no sticking around to see whether someone like U2 could break on their third album. I mention U2 because of course I passed on them.

What’s the story behind that?

I knew Paul McGuinness who was managing them, and I went to Dublin to see them and I thought, this boy Bono is fantastic, he’s a star. But I couldn’t hear any hit singles. I’d just started as an A&R man and I knew I needed a hit, otherwise I’d get fired. So I passed on them and went with Stray Cats instead. I’m very glad I did because they had a hit straightaway.

How did you go about meeting John Hughes?

Well, I was an A&R man for Arista, and then I moved to WEA and that was tricky. When I left there I managed The Beat. But they split up because some of the band wanted to tour in America and some of them didn’t want to leave home. And of course the ones that didn’t want to leave home went on to be the Fine Young Cannibals and sell eight million records. Anyway, I went to the States on tour and I was visiting my friend Kelly Le Brock on the set of Weird Science and I got talking to John Hughes who was a complete Anglophile. I very quickly found myself music supervising his films which was obviously a huge privilege. It was very hard work, but it gave me the platform to place all sorts of great music from England into Hollywood movies. I’m forever grateful to John for that, and also for the chance to watch filmmaking over his shoulder. It was another fantastic education.

He must have been an incredible person to learn from.

Yes. In fact he slightly spoilt you because you would read a new script and everyone would go, “Yeah, okay. We’ll make that.” Only later, as a producer myself, did I have to read endless scripts which were bloody awful. So he spoilt one because as a writer he was so good – the structure was so there, the jokes were so obvious, you liked the characters. As a person he was either your best friend or he wasn’t talking to you, the light was either on or off. That’s not really the perfect character for a director, so his real forte was writing, and it was great to be able to read his scripts at the first draft. And frankly, they didn’t change much from first draft to third draft. On set as a director he was quite playful – he’d say, “You have to speak the lines that I’ve written, but once we’ve done that then you can play around and try whatever you want.” That freedom comes from being a very powerful director who can spend money.

What was the process of music supervising his films? How much creative input did you have?

John was very knowledgeable, particularly about English music. He was a terrible cigarette and coffee drinker, and he would stay up all night drinking coffee, smoking cigarettes and listening to music. So we would go to his house and just try different tracks against picture until we found what would really work. It was an incredibly exciting process – he would try something, it wouldn’t work, I’d try something, it wouldn’t work, and then that would remind him of something else, he would try it, etc., etc. It was that process that led to, ‘Oh Yeah’ in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, and so on. People say, “Was that your idea or was it John’s?”, Johns! And it wasn’t just me and John – we’d invite other people from the office along and they’d bring their records. It was a remarkably democratic and enjoyable process. Some other directors are not like that.

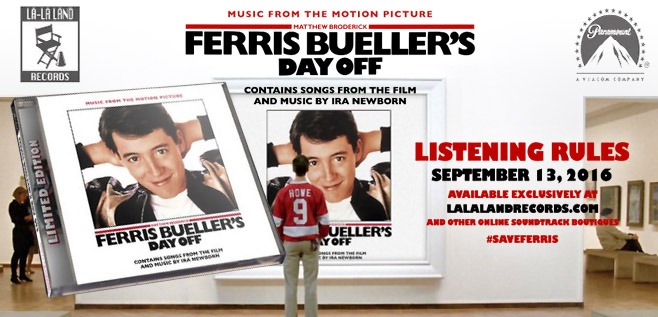

Ferris Bueller’s Day Off has such a great soundtrack, but it wasn’t actually ever released because John Hughes didn’t want it to be, is that correct?

Yes, partly. And partly there were rights issues and we were in the process of leaving Polygram Records, I think, and moving to Universal. The Beatles were upset because we’d licensed ‘Twist and Shout’ – there’s a street parade scene in the film with a street band, including a brass section, so we added a brass section to their track which they didn’t appreciate, understandably. And therefore they would not give singles rights to the one track that had gone back in the charts. So the idea of having an album without the hit single on it was tricky, etc., etc.

But it’s now getting a release?

That’s right, by the label La-La Land Records, and I did an interview for the sleevenotes, as did James Hughes (John’s son). It really does look like a good package.

What were some of the musical highlights and memories for you from that project?

Well, I mentioned Yello with ‘Oh Yeah’, because it is so distinctive. Also ‘March of the Swivelheads’ by The Beat, which is the music when Ferris is running through back gardens, jumping over the fences. It’s a great scene and it’s the perfect music and it was one of my bands, so I was thrilled. John was so sweet; he would let me put my bands in there. You don’t realise what a generous thing that is until you work with other people who just aren’t that generous. We also put The Dream Academy in the sequence in the museum which was really lovely. So you know, I just have a lot of fond memories from that movie and, of course, when the movie’s a hit, you have a better feeling for it. The movie that I worked hardest on was She’s Having a Baby, which sadly didn’t perform so well at the box office.

What was your favourite John Hughes project to work on as a music supervisor?

Well, I think She’s Having a Baby and Ferris Bueller were two of the highlights. We had a lot of fun with Planes, Trains and Automobiles. We did a country soundtrack for that – We went to Nashville and recorded with Steve Earle and Emmylou Harris and all sorts of really great Nashville types. But then when we tested the film the audience said, “Well, we love the film but not the music, it’s hick and country.” So we had to take a lot of it out, and that was really upsetting. But I got the Fine Young Cannibals to do a hip track with Steve Martin and it was a great privilege to work with Steve because he was a lovely man, as was John Candy. It was a great film because you had two great stars; and they were both extremely nice people.

How have you seen sync develop over the years?

If you sliced the revenue cake up back then, syncs were a much smaller part compared to unit sales and publishing. But now with the decline in CD sales and the income from streaming being so much less, if you get a sync it represents a huge chunk of your annual income. It’s interesting that culturally it’s less important – You used to be able to sell soundtrack albums, which now you can’t. Occasionally people do, but it’s not a business like it was. But financially, the publishing companies and the record labels are much more focused on sync now.

Featuring in a John Hughes movie must have had a great impact on an artist’s career.

Yeah, absolutely. I think it gave an artist visibility in America particularly. And people talk about it still today. When I read those artist’s bios, they always mention it because it is a mark of approval. At that time there was no better filmmaker for showing you what white middle class America was like. From growing up as a teenager and all the way through to She’s Having a Baby, getting married and having your first kid, and in fact Uncle Buck is a continuation of that, Home Alone is a continuation of that. All of that work was really just him examining his life growing up in the suburbs of Chicago as a white middle class guy.

Thank God he was such an Anglophile. I never went there, but I understand that later in his life he had a lovely ranch outside Chicago, and he was turning the garden into an English garden. So the Anglophile continued but with his new passion, which was gardening.

After working as his music supervisor he then asked you to run his film company. What was it like transitioning from music to being a film producer?

Well, it was great because I already had the working relationship with him and the trust. That’s why he wanted me there, because he knew he could trust me. He parachuted me in – Home Alone had already started shooting and he was very unhappy with the producers that he had on site, there was all sorts of friction. So I came in to make sure that Chris Columbus, our director, was happy and that John got what he wanted which was always the same – to shoot the script and then do whatever the hell you want. So we went in and we got it done, and when we previewed the film for the first time we thought we had a disaster on our hands. If you look at the structure of Home Alone, you don’t get a big laugh until about two-thirds of the way into the film. There’s an incredibly long preamble of setting up everything.

So at the preview we stood outside, because you don’t want to sit and watch the film that you have been watching for months, and we waited and waited and waited, and no laugh. We were almost suicidal and then the laughter just started and it never stopped. And so the first film I produced for him was this giant hit, and I thought, well, this is fun. This is the job for me. And then I went on to produce three films that bombed, so that’s just the way it goes. What’s great is that if you have good people around you it’s a team effort, and that’s why it’s so hard to make great films because you have to get the team right.

What was your experience working with John Williams on the score?

Fantastic, in that you just sent him the film and he sent you back this score that’s perfect. Comedies require score that underlines the gags – you’ve got a lot of talking heads and a lot of dialogue and you cannot fill it up with music. So with Home Alone and Uncle Buck and films like that there’s a lot less music.

What was it like working with huge talents such as Macaulay Culkin and John Candy?

John Candy became a good friend. I went to work for him when I left John Hughes, when I couldn’t take Chicago’s winters anymore. And Macaulay was just a sweet kid with quite theatrical parents who kept him on quite a tight rein. If we were rushing to finish the day we’d bribe him with cash and sweets to get the lines right.

You then somehow ended up doing some music supervision for The Wonder Years. How did that happen?

Because I was working in the States, I got embroiled in the first series of The Wonder Years, and it was a cracking experience, but also very demanding. John got a bit shirty about me doing two things at once, understandably really, so I left, which is a shame because I loved that series. It’s a great show because the music is used so cleverly by the director and the producers and the writers.

And in addition to all of this you also have a lot of management experience, and you currently manage AC/DC’s Brian Johnson?

Correct, that’s who just called, and I have to call him back!

Please send our apologies for holding him up!

Don’t worry. He’s a sweetheart and I’m sure he won’t mind too much.

What’s it like working with him? It’s extremely unfortunate that he had to leave the recent tour.

Yes, because of hearing issues. He is not alone – if you stand in front of these very loud rock bands for 40 years for two and a half hours a night, it’s bound to happen. I went to an AC/DC concert last year and I could hear bells ringing for at least an hour and a half afterwards.

But other than that he’s an incredibly funny man and I have the great privilege of working with him on a couple of TV shows. We’ve done a TV show called Cars That Rock, because cars are his other passion, and we’ve just made a pilot for a Sky Arts show. We’re going to do the making of a big tour and we started with Metallica and their 1992 tour that ended with them supporting AC/DC in Moscow. Sky Arts want to put that out in spring 2017, something like that. Brian is so good at chatting to people, he’s so good at broadcasting. He’s got a beautiful voice and he just knows how to fill empty air.

Where can we check out Cars That Rock?

It was on Discovery and they do repeat it quite a lot. I think there’s also one episode on YouTube. I’m very proud of that show – each episode is a different car, and we go into the history of it which Brian is incredibly knowledgeable about. Then we look at what they’re doing with the cars now and we pursue certain stories. So with Minis we looked at Michael Caine and The Italian Job. You just follow storylines and tell stories.

In a past interview you said that it’s basically you facilitating his car shopping!

Yeah, that’s right. We’ve done two series and he’s bought three cars – a Mini from Paddy Hopkirk, a Mustang from Richard Petty and now a Bentley Continental. And actually we were talking about doing a third series only yesterday. He admitted that’s he’s told Paddy Hopkirk that if Paddy kicks the bucket he’s got to sell his house to Brian. So I said, “Oh, so it’s three cars and a house now!”

And of course AC/DC is such great music to drive to. How did your working relationship with Brian begin?

Yeah, that’s right. I started working with Brian when I persuaded him to do his autobiography, Rockers and Rollers, and each chapter was a different car. That made it incredibly easy for him because he had stories to go with all these different cars, and when he pieced them all together you had his life story.

That’s amazing. A recent article claimed he may be ready to go back on stage soon. Is that the case?

No, that was a slight misinterpretation. He has found a hearing doctor who has come up with a system which would enable Brian to perform on stage again, but not necessarily with a rock band doing two and a half hours of incredibly loud music. The doctor has a system but he doesn’t have it miniaturised. So you know there’s hope but it’s still light at the end of a long tunnel. There’s very few rock musicians of Brian’s age who have not got some issues in that area.

So you now primarily work in television?

Correct. There’s Cars That Rock for Discovery, and the Sky Arts show I just mentioned. I’ve also got a comedy with UKTV – it’s a half-hour comedy written by Ian La Frenais and Dick Clement. I also worked on the reboot of Porridge which the BBC are going to broadcast later this year. We did a documentary on Porridge also last year, and I’m music supervising a documentary written by Ian La Frenais and Dick Clement for Simon Fuller about 1960s London music through the eyes of Michael Caine. It’s really Michael looking at the 60s and his success at that time, and why London was the epicentre of the creative world back then.

That sounds fascinating.

It’s fantastic, and Michael’s absolutely marvellous. He’s seen it and loved it, and we’ve got great interviews with people like Paul McCartney and Roger Daltrey. It’s a huge privilege to work on and I can’t wait to get it finished.

So you’re still music supervising and you mentioned earlier that you’re also involved in music publishing?

Correct. I have a publishing company and we publish Kathryn Tickell who was Radio 2’s Folk Artist of the Year last year and who I’m a huge fan of. I lived in LA for 20 years and when you’re there you sort of feel like you’ve got to keep moving up the pyramid. Moving back to the UK was incredibly liberating because I thought, I can do whatever I want. I can manage Jon Lord, which I did, until he sadly passed away a couple of years ago. It opened the door to managing Brian Johnson, producing television, music supervising – basically just doing whatever you enjoy, making some money and living a happy life. I have to say, I’m a very lucky guy.

Yes, you are! And it seems now that television is becoming a more creative medium than film. What are your thoughts on that?

Well, again, it reverts back to the conversation I had earlier, which is that the movie studios have to hit out of the ball park. That means they have to appeal to mass audiences, which tends to bland out the product. I think they’ve been very successful with their CGI films, but I think that a lot of that has to do with the fact that the process of making a CGI film is three to five years, and you can go in and redo bits along the way. The problem with filmmaking is that it’s so expensive so what you shoot is what you’ve got. You can’t go back and get Tom Cruise to reshoot something if your film isn’t quite right, whereas with CGI you can. So I tend to find that now the only films that I really want to see out of Hollywood are the CGI ones.

But if you want a drama then yes, television is a much more interesting place, mainly because you can tell a story over six or twelve hours, and you can go into much greater depth. Once you’re into the story with your binge-watching you just are insatiable and you want more, and that’s an incredibly satisfying way to consume that media. You’re also at home, you’ve got a cup of tea, you’ve got your dog sitting on your lap, whereas at the cinema you’ve got the horrible smell of popcorn, you’ve got people talking, you’re paying parking and it’s all too expensive. So I think the film business in the long term is in trouble unless they can really make the cinema going experience a lot nicer. There are moves in that direction with upmarket cinemas with wine and nice comfy sofas and all that.

But the TV industry is going to go over a cliff just like the music business because the business model is about to crumble. In America the cable bundling is under pressure, so when you unbundle the cable channels a lot of them are going to fall by the wayside because really people are going to be very specific about which channels they want. So I think the TV business is under pressure, but storytelling and creating content will continue. Louis C.K. has his comedy show that you can pay three bucks for and download from YouTube and watch, and he’s made a lot of money with that. That is a business model that will work going forward.

Lastly, are there any particular memories or anecdotes of your time in the industry that really stand out?

That’s a dreadfully difficult question to answer, and partly because when you are a behind the camera guy, part of your job is to be discreet and trustworthy. But you know, it’s all been fantastic. I can’t single something out particularly.

Where can we find you online?

I run the http://www.brianjohnsonracing.com website for Brian, that’s to do with his car stuff. I also have a publishing company called Not Them Again Music, and we’re just putting a website up so people can reach me there.

Sounds good, well thanks so much for taking the time Tarquin!

Marvellous. It’s been a real pleasure, have a lovely day.