As we continue our ‘Projecting Trends’ series, digital strategist Bas Grasmayer takes a look into the history of online music discovery, and what the present tells us about the future.

It seems that every other consumer-facing music startup wants to help people discover new music. Platforms like Spotify or Pandora also have a strong interest in connecting people to great music, because time spent on service equals ad revenue.

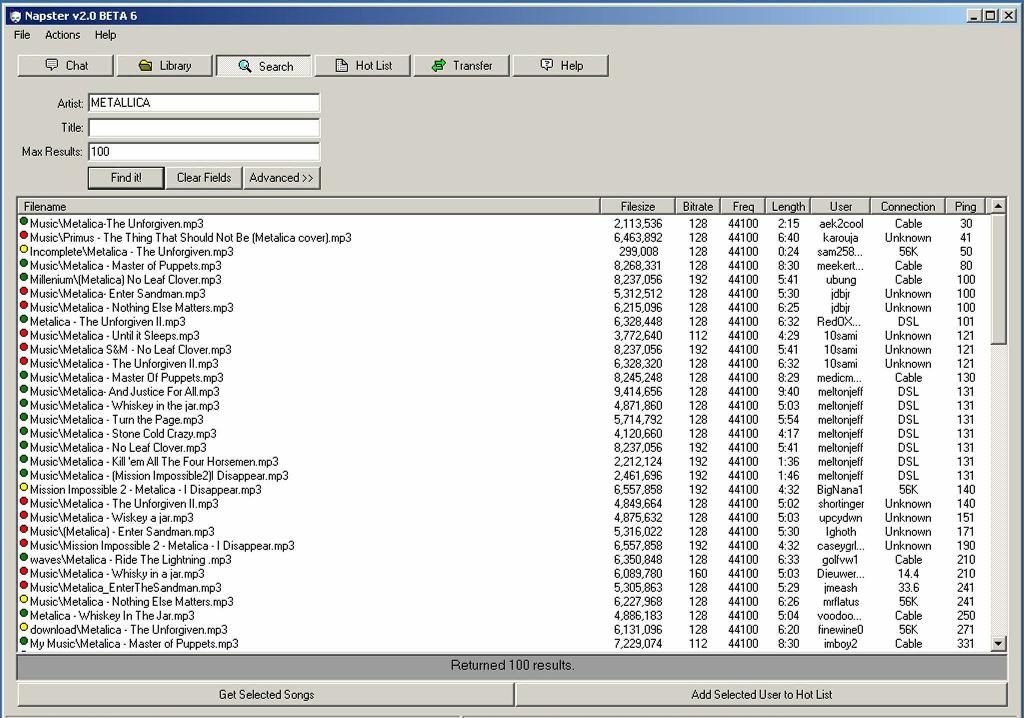

IRC

The online chat protocol IRC let people set up servers and channels to discuss any topic. Some people used it to set up channels with bots that would serve files to users on request. Messenger bots are actually quite old school and were one of the first ways, after Usenet, in which people were pirating music online. They’d join a channel, check in on the announced new files available every now and then, and would then send a message to a bot to retrieve the file they wanted. After messaging the bot, the bot would send the file to the user.

The discovery mechanism was basically sitting in a channel and seeing what new files were available. Passive like radio. Often there would also be a bot that you could query to find specific files or get a list of everything available.

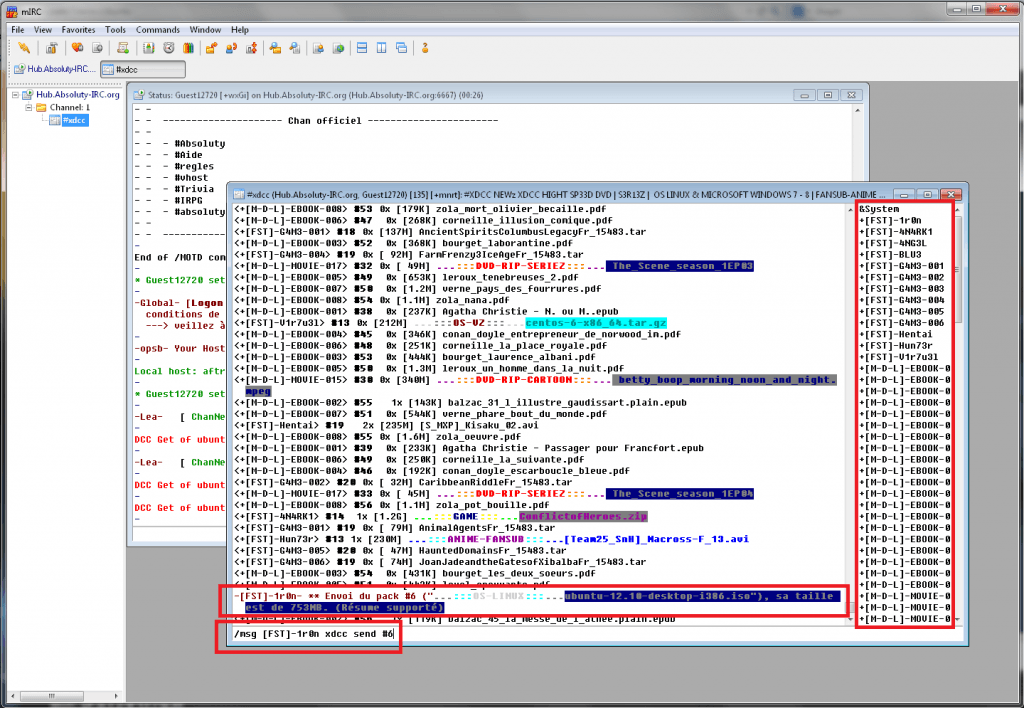

Napster

Then came Napster. The service represents a pivotal moment for the music industry. The startup showed how the internet’s promise of free flows of information could be applied to music. Despite its reputation as a pirate service, they had believers inside the music industry too, with BMG investing in Napster. It failed to go legit on time and become a subscription-service, but not before changing the way we discover music.

Napster made music less scarce. It was easier to use than IRC bots and Usenet, so more people engaged in it. For this first generation of file sharing service, the search box became the key to music discovery. Type a phrase, see what comes out and pick what you want. Or, in terms of discovery, pick the tracks you don’t know yet.

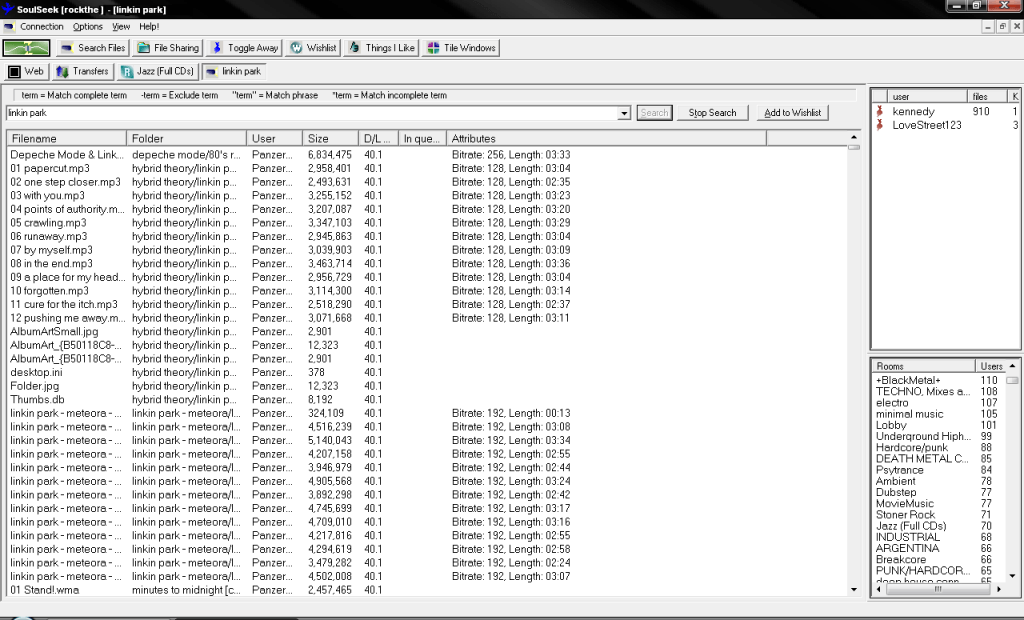

Soulseek

The next big upgrade for pirate services and music discovery was Soulseek. Instead of letting users download single songs, it would let users download entire folders. There were chatrooms based on music tastes. Independent artists would use these chatrooms to promote their music. You could make wishlists of content, so if something was unavailable, you could easily grab it at a later time (remember: it all depended on users being online). You could save queries, so you could return to them later and see if there’s anything new.

Perhaps most importantly, you were able to browse other users directly, searching through their folders. If you were a kid in Austria, interested in underground hiphop, but having no way to get those CDs in your own country, suddenly you would be able to interact with people from the US and browse through their entire underground hiphop music archives.

In other words, Soulseek made the music discovery process much more social and added a new behaviour: social browsing as a music discovery mechanism.

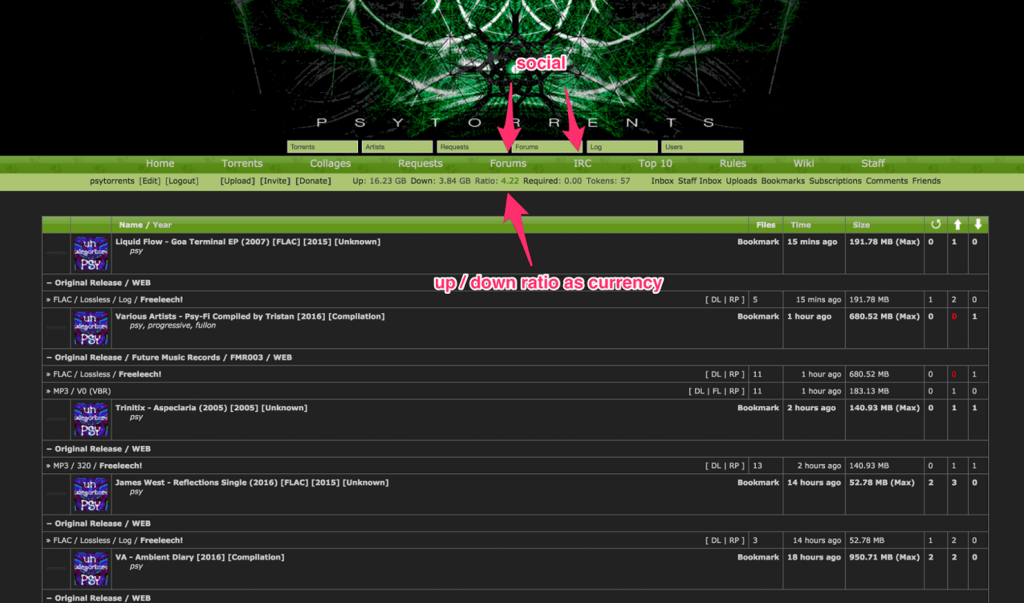

Private Torrent Trackers

The rise of torrent technology changed the piracy landscape. Torrents were much more efficient to the end user than peer-to-peer transfers. Torrents chop files up in small packages and transfer them from multiple users, sometimes hundreds or thousands. A problem for early peer-to-peer networks was that if the user you’re downloading from went offline, you would no longer be able to download.

Private trackers often focus on a particular style, genre or set of sub-genres. It creates social communities akin to the IRC or Soulseek chatrooms mentioned earlier. Because everything happens through a centralized tracker, the platform knows exactly how much users are sharing and taking, seeding and leeching. There are lively forum discussions about music where it promptly displays people’s upload / download ratio. This is a form of social currency, a status symbol.

If you share a lot, you’ll be able to download more. Often these trackers penalize people who have poor ratios, for instance by revoking their right to download more music until they improve their ratio. All in all, the discovery process is a combination of all the aforementioned dynamics, but with more of a communitarian focus.

An important difference is that torrents made it easy to download LOTS of music. Either by just hitting the download button on all the albums, or by adding the RSS feed to your torrent client, so that it would automatically download everything as soon as it hits the service. It’s a good tactic to make sure you’re one of the first downloaders, meaning you’ll upload it to more users than the downloaders who come later. Feed subscriptions were often reserved for high ratio users.

Now comes the important implication: this behaviour means that hard drives would get filled with more good music than users could possibly listen to. This over-abundance created a new problem. One that pirate services couldn’t tackle on their own.

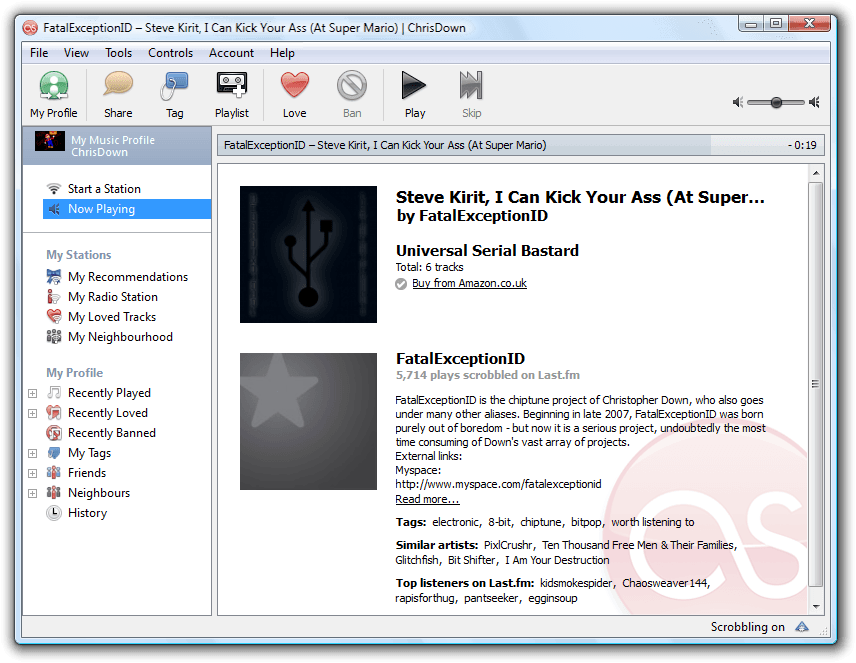

Last.fm

A landscape where lots of people have music on their hard drives, often mostly pirated, and more than someone would be able to reasonably enjoy. Listening to everything once is doable, twice is a challenge, three times would be near-impossible.

Last.fm set out to make use of this fact by creating a scrobbler that would automatically track what songs people are listening to and save this information to their service. Through this data grab, it could understand that listeners of a certain artist were also likely to listen to a particular other artist. It became the first widely used music recommendation engine. Compared to music services nowadays, Last.fm was highly social, creating discussion groups, pages for user profiles, artist profiles, genres and communities spawning around tags.

Its aim was to make it easier for users to find relevant music. You could tune into a personalized radio stream, as well as radio streams where you would pick a tag or artist as a departure point. It was great for artists in smaller genres who had trouble getting their name out. Suddenly they started getting themselves found through algorithms.

It was an important step forward for music services and though people could stream directly from the service, much of the user behaviour around acquiring music didn’t change.

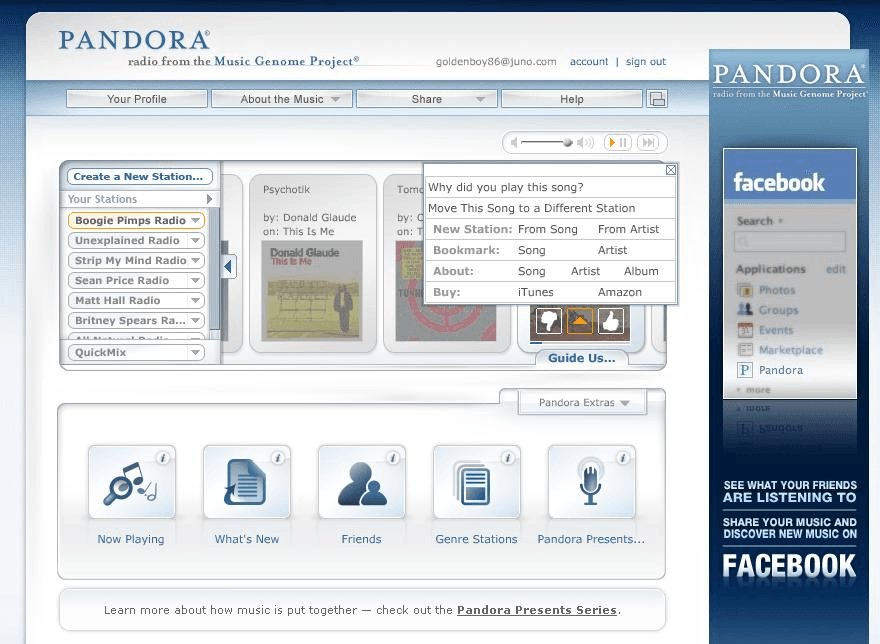

Pandora

It was Pandora that took things a step further. Last.fm’s strategy was to tap into existing user behaviour and build something on top of what users were already doing: listening to music with WinAmp or Windows Media Player. Pandora gave users a new place to listen to music. It didn’t brand itself as a social music service – it branded itself as personalized radio that learns from your tastes.

Pandora and Last.fm played important roles in the dawn of personalized internet radio. Radio that is interactive, and learns from your tastes. Instead of making users do all the work, they were truly music services: making the lives of their users easier and improving their discovery process.

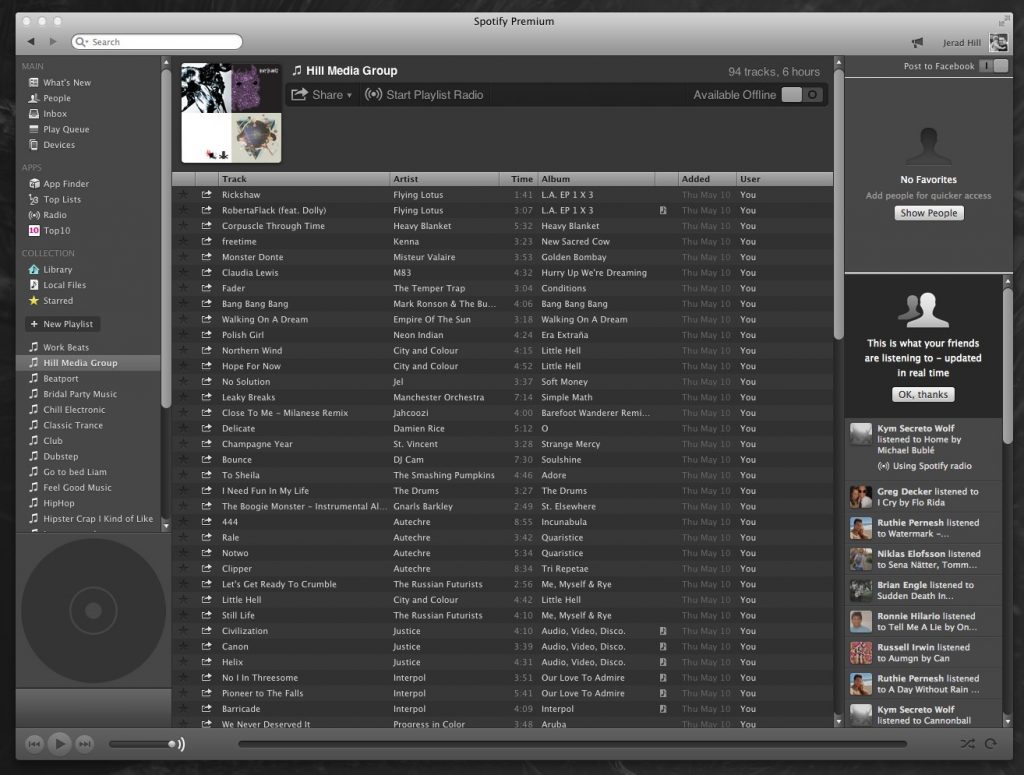

Spotify

In the late 2000s, Spotify introduced a new element to the music discovery landscape. Playlists. Playlists were not new, but being able to easily share playlists with friends, and having them able to listen to it immediately without having to download the music, was game-changing.

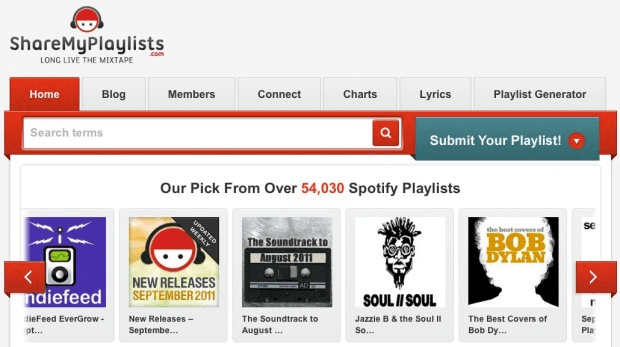

Spotify created an API to let developers access data and functionality of the service. It spawned a landscape of music apps. Early playlist curators faced a problem though. How could they share their playlists beyond their personal social graph? Spotify made improvements, like showing playlists in search results, but the most important player at the time was ShareMyPlaylists.

ShareMyPlaylists was a place to share and discover new playlists. It seemed to have been hacked together with blogging software, and at first it wasn’t all that great, but it thrived because it was the most important (and at one point the only) place where community members could easily dig into curation. It later rebranded to Playlists.net and was acquired by Warner in 2014.

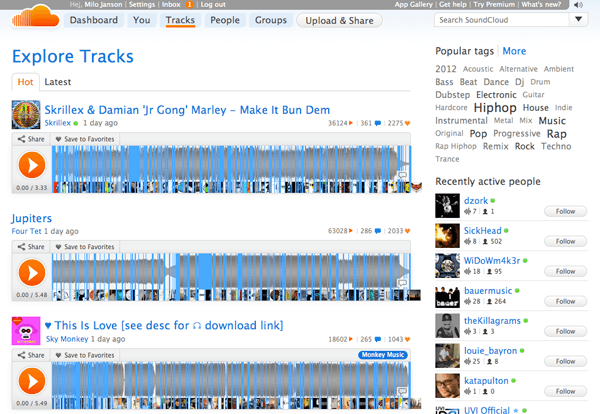

SoundCloud

Another music startup with Swedish roots popularized a different discovery mechanism at the same time. It let users sign up, upload their music, and follow other artists. Basically: follow a bunch of artists you’re interested in and never miss a new upload. Timed comments allowed for the community to leave feedback on each other’s tracks, as well as a way to discover people with interesting perspectives. This focus on community and direct-to-artist subscriptions turned SoundCloud into the popular platform it is today.

It also had the tag system popularized by Last.fm, letting users browse through tags. Another feature seen in previous services, groups, let users gather music based around certain criteria. The latter was made redundant recently.

Shazam

Then multiple things happened: our mobiles became more powerful. They started to be always-online, and music recognition algorithms started getting accurate. Shazam built a massive database to be able to recognize music that people would send in by holding their phone’s microphone up while a song was playing. A new way to discover music was born. Hear a track, identify it, and then purchase it on iTunes.

Shazam is important, because it made perfect use of converging trends to create something new. Not just a new app, but a new music behaviour, a new way of discovering music.

Beats Music

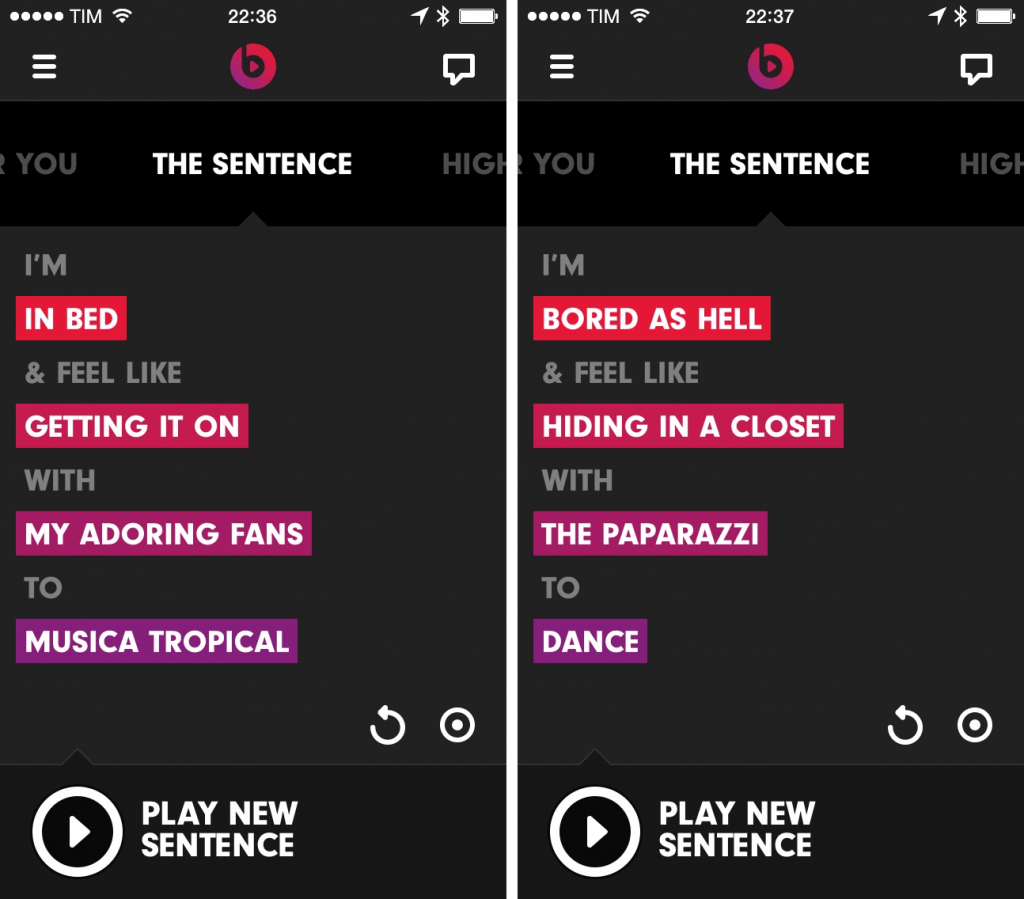

Before Apple Music, there was Beats Music. While the service itself was not that revolutionary in terms of creating new ways to discover music, it had one feature with tremendous importance. It was called The Sentence.

It allowed you to describe a situation and then it would spawn a stream for you. Instead of playing off of related artists, or through genres, the product people showed a great insight into current day music listening attitudes. We’ve gone from an aesthetic orientation to music, to a utilitarian orientation. As Brazilian consumer researcher Thiago R. Pinto recently put it: “Music for new generations is not about reflecting their unique personas, but a mirror of the activity he or she is performing.”

Spotify reloaded

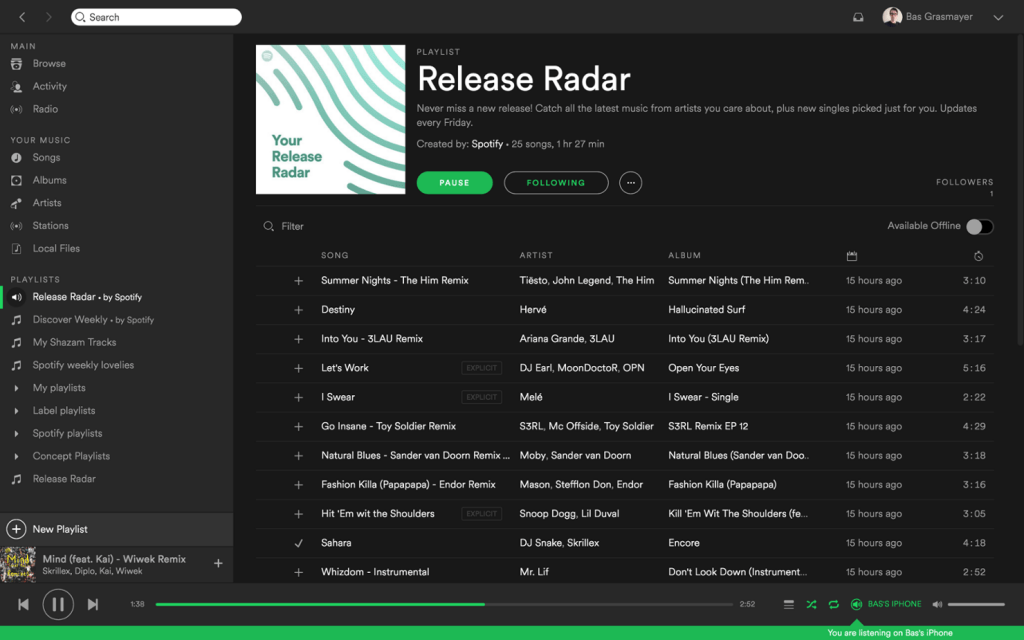

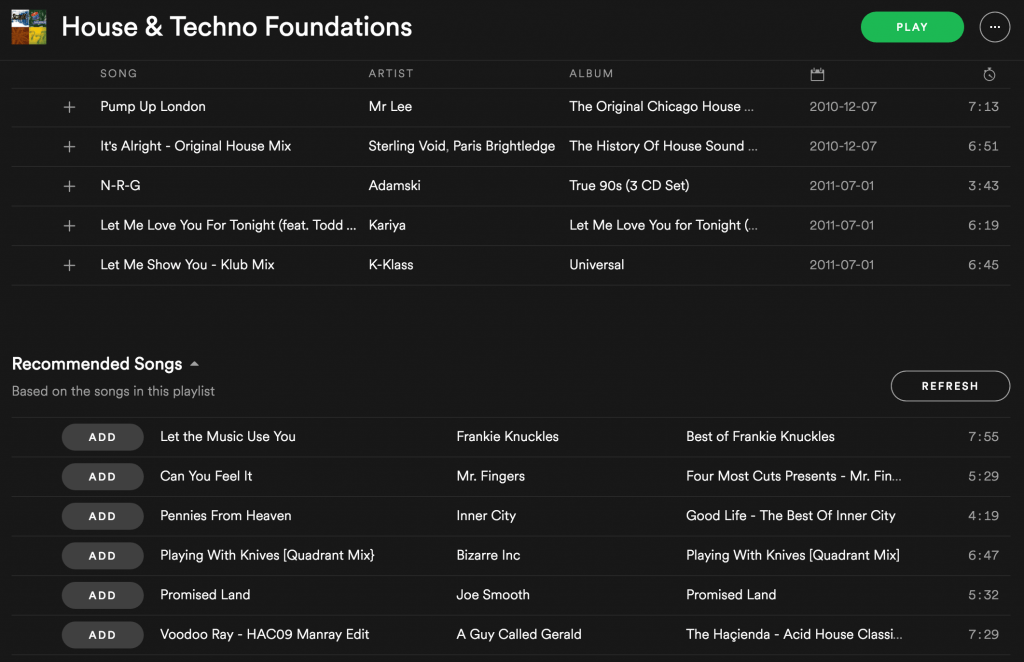

Spotify kept pursuing its playlist strategy, but decided to decrease the dependence on the human factor by acquiring music data company The Echo Nest. Now, its algorithms create weekly playlists for all its users: Discover Weekly and Release Radar.

As pointed out previously, it marks an important direction for Spotify which will influence the online music economy. The person behind this new functionality is Matt Ogle, who was one of the product people for Last.fm until 2010. In a way, these playlists are a hybrid of the Spotify model and the personalized radio model established by Last.fm and Pandora. It’s what else Spotify is doing that’s important for the future.

Below every playlist, you’ll find a ‘recommended songs’ section. Spotify is carefully employing its algorithms to guide user behaviour and to help users get a better experience out of the service. It’s this algorithm-driven innovation which will be behind the next generation of music discovery.

Breaking artists

Two notable examples of algorithms being used to predict which artists are about to make breakthroughs are Pandora’s new charts and Shazam’s Future Hits chart. Both look at their data sets and when they see a trend displaying a surge, they add the information to the charts. Back in May, Shazam predicted this summer’s hits. How do you think they did?

More innovation

The key to next generation of music discovery is comprised of three vectors:

- music as a utility;

- real-world context, with mobile devices as the key;

- and guiding user behaviour through algorithms.

There have been great advances in machine learning in recent years, so the latter has some extra weight.

The reason why I started with pirate services is to highlight what they innovated and how it made a lasting impact on the services we now use every day. Luckily, most innovation has moved to licensed services nowadays, because it’s just much easier to attain licences on decent terms than 15-20 years ago. With the rise of good legal services, the appeal of piracy has shrunk.

Streaming exclusives are a threat to this fragile status quo. The marketing messages of music streaming services often mention having your music “all in one place” (Apple Music) or “all the music you’ll ever need” (Spotify). This gives users the feeling that they’re already paying their music access tax and will not hesitate to pirate an album released as an exclusive. They might be wrong, but exclusives are a danger to sustainability.

If the status quo is broken and piracy makes a big comeback, expect more innovation to happen in the unlicensed domain, creating new behaviours and methods for music discovery.

However it plays out, expect the next few years to bring new discovery methods which understand the user and the context of the situation that they’re in.

1 comment

[…] Every product has a philosophy behind it and sometimes this philosophy can change the interfaces of a whole space. Look at how Tinder changed dating with its left-right swipe interface: not only a newcomer like Bumble decided to go for that, but so did the incumbent OkCupid. Or take Snapchat and the way its format influenced Instagram Stories and TikTok. This happens in music too, where some of the biggest influences can be traced back to IRC and Napster. […]