Bas Grasmayer takes a look at the changing role of the consumer, the ways in which music is evolving, and some of the business models attached to it.

In the last century, the proliferation of the record as the default way to listen to music turned it into a solitary, static experience for people who previously connected to it as participants.

Social trends like consumerism and individualism further drove the experience from personal to isolated through increasingly portable music players, from Walkman, to Discman, to MP3 players.

Our generations’ specific experience of music has been unique in history. Music was always participative and never quite as static, by default, as it became in the second half of the 20th century. Now, with technology in our pockets that’s more powerful than the computers on our desks just a few years ago, music is starting to shed its temporary static characteristic, with and without the creators’ doing.

A look at the changing role of the consumer, the ways in which music is evolving, and some of the business models attached to it.

Consumer as creator

Ten years ago there were many discussions about ‘remix culture’ as a concept. Now we live inside it. Through internet memes, images get shared with captions to put their meaning into a new context. Online creator communities, like the nightcore subculture, do the same with music.

It has become so easy to alter and distribute works that recorded music is used as a medium to rapidly communicate creative concepts with groups of peers, primarily on Soundcloud.

Apps like Musical.ly, immensely popular among teenagers, blur traditional consumption and creation and let users create short videos with their favourite music and then share it to their friends.

Interactivity

For years now, Smule has made mobile apps that let users play around with music. Their apps feel like music games, with Magic Piano being reminiscent of games like Guitar Hero. Their big hit is Sing! Karaoke, which lets users pick tracks and then partners them with other mobile singers around the world.

On the audiovisual side there’s Whitestone, named after the inventor of album artwork, which have recently released interactive experiences for the albums of Daedelus and The Gaslamp Killer.

Whitestone’s on to something and there appears to be a wider trend of interactive music videos, such as Cee Lo’s ode to Robin Williams, which displays the song’s lyrics being typed into Google and lets users switch between various types of results, like images or videos.

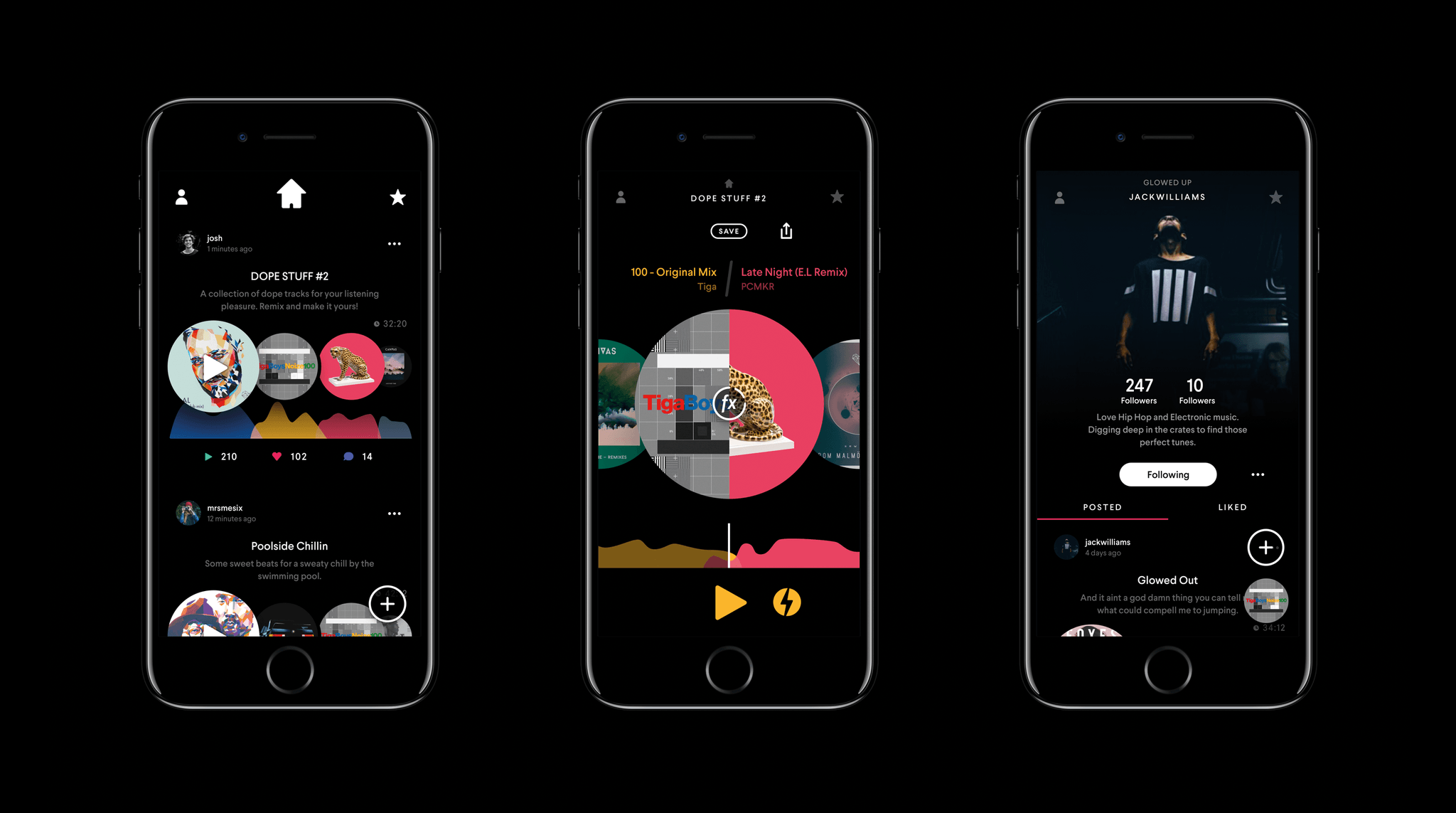

Another category of apps enabling people to get creative with existing music are DJ apps, like Traktor’s mobile app or Pacemaker. The latter makes mixing especially easy by letting users import their Spotify playlists which the app’s artificial intelligence can then mix for them. Users have the freedom to go back and alter the transitions, as well as add extra effects, some of which can be unlocked as in-app purchases.

Pacemaker’s business model mimics one already popular in mobile games. Give away the basic functionality for free and charge users to unlock extra functionality. There’s a takeaway here for music apps in general: if you get the experience right, you can make more money by charging for features than by gating the content.

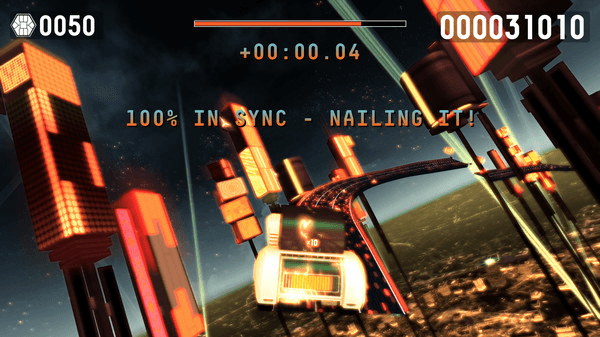

Many game developers are acutely aware of the importance of music to their game’s experience. Some so much so, that they use algorithms to let the user’s pick of music design the game. Games like Audiosurf and Riff Racer let you choose a song and then automatically generate race tracks based on the track’s qualities.

Adaptive music

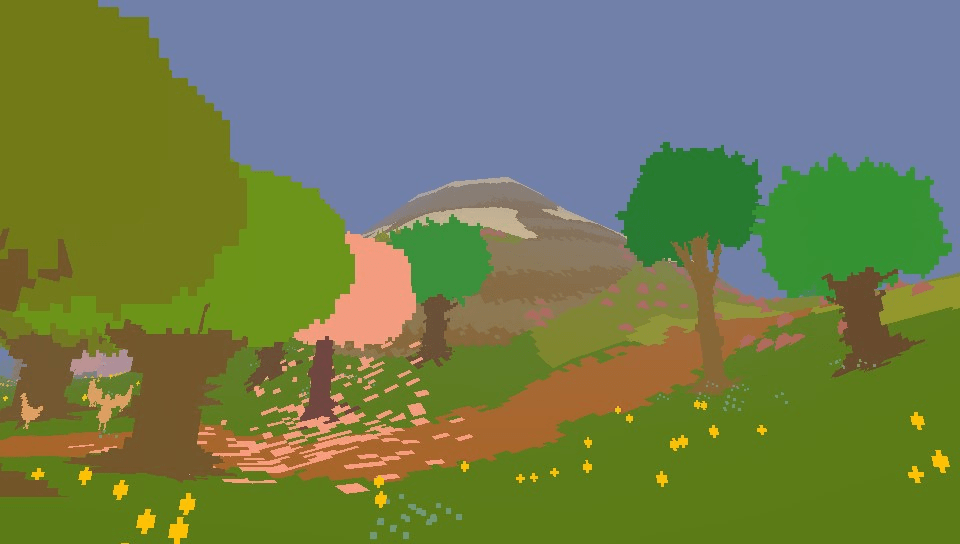

Also popular in gaming are adaptive soundtracks that react to the player’s actions. A great example is Proteus, a game that encourages players to wander around an island, discover new areas, and enjoy the way objects around them influence the soundtrack.

Although the graphics are basic, the experience is far from it and very trippy. The changing seasons, different weather conditions, time of day, and varying ecosystems all have an impact on the music.

With powerful connected devices in our pockets, activities like these don’t need to be limited to video games. A great example is Pokémon Go. Pokémon had long been confined to virtual worlds inside video games, but by using augmented reality, the creators of the game have been able to layer the game onto the real world.

For years now, app creators and musicians have been designing ‘location-aware’ albums, like Bluebrain’s musical map of New York’s Central Park, Listen to the Light. Another team of developers built an app for the Inception movie which gives people a soundtrack that interacts with sounds from their real world environment. Their app Dimensions, which had a similar augmented music aspect, notified users of nearby objects to collect in similar vein to Pokémon Go.

One of those apps’ principal sound designers, Rob Thomas, collaborated with Massive Attack earlier this year to develop a music release which remixes itself based on the listener’s environment.

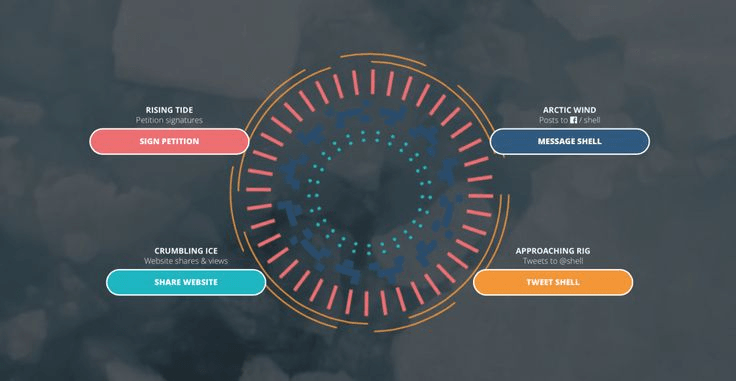

One of the most important uses of adaptive, and interactive music so far, has been Requiem for Arctic Ice, a collaboration between We Make Awesome Sh and Greenpeace. It turned an online protest into a musical protest – creating a composition that would react based on social media shares and petition signatures. A successful one at that. Shell finally announced they were cancelling their Arctic drilling plans.

A more engaging future

We all want eyeballs and eardrums and the information age has set up an intense competition over them. Taking into account the fact that our devices are becoming more powerful, we can build more engaging experiences, so that once we win someone’s attention we hold it a little longer.

Bands, brands, app developers and virtual experience designers are all ready to take the leap and redefine what it means to make music. Are you?

Subscribe to our Synchtank Weekly newsletter to receive all of our blog posts via email, plus key industry news, and details of our podcast episodes and free webinars.

1 comment

[…] believe that music’s future is non-static. It gained a default characteristic of linearity in the age of the recording, meaning: a song will […]