In this edition of our Projecting Trends series Bas Grasmayer takes a look at the music streaming playlist economy, from gatekeepers and business practices, to how playlists are influencing music itself.

Playlists have become the default for listening to both new and unfamiliar music. Instead of digging through complete releases and saving them to our libraries, the design choices of companies like iTunes and Spotify mean we use playlists as the interface for music collections.

What are the implications on the business side and how do playlists impact the music itself?

Streaming as the new radio

Every trend has a countertrend. Back when Last.fm was still one of the most important players in the online music landscape, people were excited about what music recommendation algorithms would mean for the future of music. The rough idea behind these algorithms was that if you listen to the same bands as someone else, but they listen to a band you haven’t heard yet, then there’s a good chance you’ll like that too.

There were many that didn’t believe in the algorithms, or felt that human curation’s value was too great to dismiss. Particularly Beats Music (now Apple Music) was very vocal about the human curation aspect, the countertrend to automated algorithms, despite also offering a recommendation engine themselves. Now, with Spotify employing a key former product person from Last.fm, we’re back to (much more advanced) algorithms with Discover Weekly and Release Radar. While both of those playlists are important for driving streams within the Spotify ecosystem, it’s the curated playlists that are key.

“While both the Discover Weekly and Release Radar playlists are important for driving streams within the Spotify ecosystem, it’s the curated playlists that are key.”

A whole business of pitching playlist owners has emerged. Often, but not always, these playlist owners work for the music service themselves. Pitching them is the new radio plugging, but due to the nature of on-demand streaming the dynamics are different.

Skip rates as performance indicators

While essentially the same as pitching a blog or a DJ, one has to carefully consider the way playlists work and the metrics that matter. In a recent discussion at the Eurosonic Noorderslag conference, Soundcharts founder David Weiszfeld mentioned that skips can “hurt” your track. In other words: you may be able to convince the streaming curator to put you on their list, but if too many people skip your track, it is then removed and is unlikely to go on other lists.

A diagram from the Soundcharts website.

Skips can easily be influenced though. Typically there are benefits to being lower on a playlist: you’ll get less streams, but by the time people reach your track they’re likely in lean back mode. An example that was used in the aforementioned discussion was that if you’re pitching an upcoming artist and they get placed at the top of a Hits playlist, despite not having a clear profile yet, then you’re going to see a very high skip-rate. People are tuning in to hear familiar hits, and although your track may sound like a hit, if it’s the first thing they hear, they’d likely skip it due to lack of familiarity.

So, the balancing act for labels and others pitching tracks is to find the right balance between audience size, number of streams, and skip rates.

“The balancing act for labels and others pitching tracks is to find the right balance between audience size, number of streams, and skip rates.”

Building your own playlists

The currency of the internet is attention, so a successful online strategy for artists incorporates ways to hold people’s attention over time. By running your own playlist, you can connect people to you and get them to form a habit around your playlist. This is a good way for artists to keep fans up to date on what inspires them (see Porter Robinson’s playlist for an example), for radio shows to highlight what they’re playing or what guests they have on their show (see the Diplo & Friends playlist), and for labels to keep fans up to date on new music (see Brand New by Spinnin Records).

“The currency of the internet is attention, so a successful online strategy for artists incorporates ways to hold people’s attention over time.”

Some opt to just build a huge music collection over time, while others switch out content every week or month, creating ephemeral media which is useful in building habit: people have to come back every week or they’ll miss the new instalment. This is also what’s been driving the success of Discover Weekly, or Snapchat for that matter.

But all’s not well for owned playlists: recently Spotify has been demoting user-generated playlists in order to prioritise their own. It may have something to do with their goal to IPO, with their product reaching maturity and needing to branch out beyond early adopters, and Spotify thus wanting more control over the music experience – even in search results.

While it could be argued that user-generated playlists fuel growth for Spotify, it seems like they’re content with their discount strategy and are focusing on the onboarding and conversion of these new users.

Is this changing music itself?

Pop albums are becoming longer to better benefit from streaming dynamics and generate more revenue. If you have a hot release, it’s not unlikely that all of your tracks will enter the charts, rather than just the single. So it makes sense to add a bigger number of tracks to an album, since you’ll claim a higher proportion of the charts and end up generating more plays. Track length is also at stake, since pay-per-play means an album with lots of shorter tracks will generate more money than one with longer songs.

“It makes sense to add a bigger number of tracks to an album, since you’ll claim a higher proportion of the charts and end up generating more plays.”

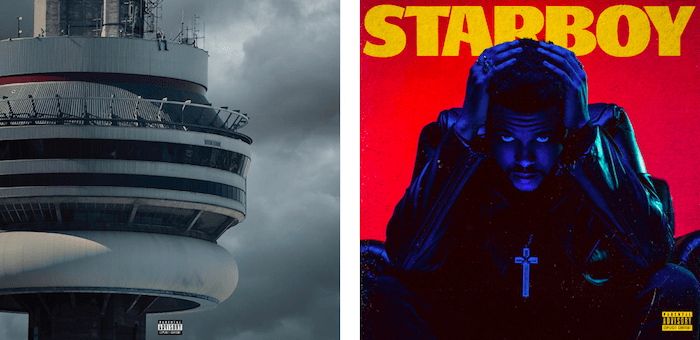

Drake’s ‘VIEWS’, which contains 20 songs, and The Weeknd’s ‘Starboy’, which contains 18.

Another interesting idea, suggested by Songflow’s Mars Mertens, is that music companies may opt for ‘playlist edits’ of tracks, a new type of radio edit. The goal of such edits would be to carry people through the first 30 seconds, when the track is registered as a play, before people skip. This optimizes revenue, track rating and position inside playlists, as well as track popularity which may also influence recommendation algorithms.

It’s an interesting thought and likely already occurring, as with albums, but for now those tracks are probably still marked as radio edits.

While the last instalment of Projecting Trends was about technological unemployment, expect a lot more playlist-related work in coming years, from pluggers, to data analysts, to technical marketeers, and of course curators.

What’s your playlist strategy? Share your story in the comments.

Subscribe to our Synchtank Weekly to receive all of our blog posts via email, plus key industry news, and details of our podcast episodes and free webinars.