In the first of Synchtank’s two-part analysis, Ben Gilbert takes a deep dive into the subject of AI to explore how automation and machine learning are changing the traditional craft of music creation. Head here for part two, where we consider how this technology is set to reshape the industry’s use of data.

As we approach 2020, warnings about “the techno-moral panic” have been heavily advertised and garishly signposted, almost like neon LED letters sparking in a black and pink skyline. Algorithms, automation and machine learning consistently prompt a suspicious refrain. “There is an enduring fear in the music industry that artificial intelligence will replace the artists we love, and end creativity as we know it,” pondered a piece in Billboard predicting the potential impact of Big Tech on our most cherished artforms.

Does such speculation seem extreme? Perhaps. For context, consider the way music composition has evolved over the past half a century. Recorded between February and September, 1966, The Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations” was the result of countless sessions at four different Hollywood studios. Costing in the region of $75,000, more than the entirety of their landmark Pet Sounds album, the single used over 90 hours of recording tape. Its creator, Brian Wilson, described the song’s completion as being like “a feeling of power, it was a rush. A feeling of exaltation. Artistic beauty. It was everything.”

In September, 2016, precisely 50 years later, Sony CSL Research Laboratory unveiled “Daddy’s Car”, “a song composed by AI – in the style of The Beatles”. Utilising the FlowMachines system, with assistance from French musician Benoît Carré, they described the recording process as follows: “Forty-five Beatles songs were given to the intelligence, which emulated the chord progressions and song structure of the Fab Four to intimidatingly accurate effect.” The result has variously been described as “a dire warning for humanity” and “the creepiest song you’ll hear this decade”.

“A new era of human originality is about to begin”

But for all its cold robotic precision and, conversely, complete absence of rock and pop mystique, it’s undeniable that “Daddy’s Car”, in many respects, presents a vision of the future for creators and consumers and not necessarily the dystopian one envisioned by The Verge. Alongside Sony Music, multiple leading technology companies are creating AI music tools that are far more interested in discovering new musical worlds than regurgitating old ones.

Lead by research scientist Douglas Eck, Google’s Magenta project features NSynth Super, an instrument that innovates around sound. “We’re trying to build some sort of machine learning tool that gives musicians new ways to express themselves,” Eck explained. These are the same pioneering motivations that are fuelling Ash Koosha, the Iranian-born, London-based electronic musician behind the AI popstar Yona, “one of the world’s foremost virtual entertainers”, who featured at the recent Barbican exhibition More Than Human. Koosha wants music producers to embrace the possibilities of such technologies, telling Dazed: “A new era of human originality is about to begin.”

Certainly, a constant stream of hardwired imagination is emerging from this sprawling but lushly fertile landscape, in recognition of the universal demographics and infinite possibilities presented by the creation of music, seemingly unmoored from the traditional anchors of formal education and technical skill. Some have quickly caught the attention and imagination of audiences and, consequently, big business. In July, Bytedance, which owns social media app TikTok, acquired Jukedeck, a UK-based AI Music startup, which will, ultimately, allow users to create royalty-free music for their videos.

“There’s nothing to fear about AI as an agnostic technology”

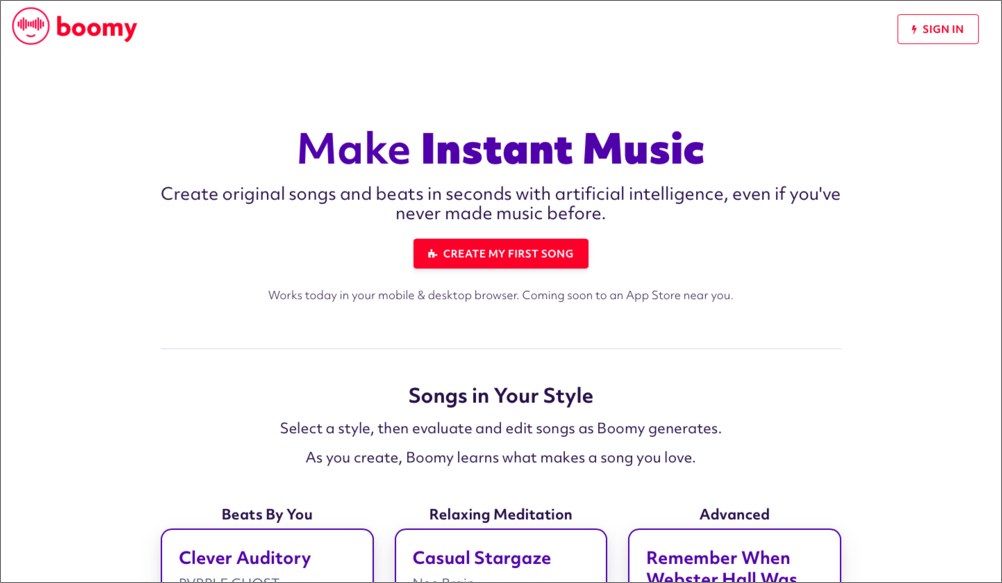

Last year, Tarynn Southern released I AM AI, the first album to be entirely composed and produced with AI, using the open source platform Amper Music. In August, DFA act YACHT discussed the influence of machine learning on their new album, Chain Tripping. Meanwhile, US-based startup Boomy, which specialises in “instant music”, has been gathering momentum with a service that allows users to create a song in seconds via the platform. Speaking to Synchtank, founder and CEO Alex Mitchell was keen to address the suspicious narrative that AI continues to inspire in some quarters.

“First, let’s realize there’s nothing to fear about AI as an agnostic technology, rather there might be things to fear about the impact of AI in the market. I’ll tell you exactly what the impact will be: way, way more people making way, way more music.”

– Alex Mitchell, Founder & CEO of Boomy

He said: “First, let’s realize there’s nothing to fear about AI as an agnostic technology, rather there might be things to fear about the impact of AI in the market. I’ll tell you exactly what the impact will be: way, way more people making way, way more music. We will start to see a flood of people who aren’t musically trained, maybe don’t have natural talent, coming into the industry and the marketplace and competing with musicians and industry folks with years of training and experience. That is scary to the incumbents!”

“Auto-Tune was met with a lot of resistance when it started becoming standardized. Now that we can look back, it’s obvious that it didn’t mean we stopped appreciating singers, it didn’t replace singers at all, nor did it affect our appetite for great singers.”

– Alex Mitchell, Founder & CEO of Boomy

But Mitchell suggested you don’t have to go far in music’s history to identify a similar, unrealised techno-moral panic. “Auto-Tune was met with a lot of resistance when it started becoming standardized,” he explained: “Now that we can look back, it’s obvious that it didn’t mean we stopped appreciating singers, it didn’t replace singers at all, nor did it affect our appetite for great singers. So what did it do? Auto-Tune enabled a whole generation of non-singers to participate in the music creation process, and music economy, in an unprecedented way; all of a sudden, you didn’t need to have perfect pitch or lots of expensive vocal training to make a song people wanted to listen to.”

Fears of creatives mirrored in concerns about ownership and authorship

Elsewhere, the fears of creatives surrounding the emergence of AI and music production are mirrored in concerns about issues of ownership and authorship. “Do AI algorithms create their own work, or is it the humans behind them? What happens if AI software trained solely on Beyoncé creates a track that sounds just like her?” questioned The Verge recently, before concluding that the situation is “a total legal clusterf*ck”. Meredith Rose, policy counsel at Public Knowledge, agrees with this assessment. “I think it’s accurate in some ways,” she commented, explaining that this territory has no legal precedent, with the debate currently founded upon the theories being debated within academic circles.

“As with any new innovation, the uncertainty around this creates a risk of exploitation. The industry is already marked by unequal bargaining power and information asymmetries, and it seems entirely possible that the legal questions – ala ‘who owns the work?’ – will be another one of those systemic knowledge gaps that can be exploited,”

– Meredith Rose, policy counsel at Public Knowledge

“As with any new innovation, the uncertainty around this creates a risk of exploitation. The industry is already marked by unequal bargaining power and information asymmetries, and it seems entirely possible that the legal questions – ala ‘who owns the work?’ – will be another one of those systemic knowledge gaps that can be exploited,” she told Synchtank.

Putting aside the complexities that surround technical and legal issues in this burgeoning field, Boomy’s Mitchell has a clear philosophy which resolutely rejects the description “AI-generated music”. “When The Edge uses a delay pedal, we don’t call his music ‘delay-generated’, we call it his distinctive style. We don’t call what Slash makes ‘guitar-generated’, so why would we call what Boomy users make ‘AI-generated’?”

Instead, he prefers to push on the angles of human engagement and creative endeavour at the company, which recently emerged from beta after facilitating the creation of more the 150,000 original songs in a matter of months. “Boomy has a simple mission: to bring the joy of making music to everyone in the world, regardless of their access to financial resources, time or even talent. Beyond the technological machinations at work, these are pure and endearing motivations, hardly unrecognisable from those that inspired a teenage Brian Wilson to start writing his first song in a bedroom in Hawthorne, California.

This is the first of Synchtank’s two-part analysis exploring the impact of AI on the music industry. Head here for part two.