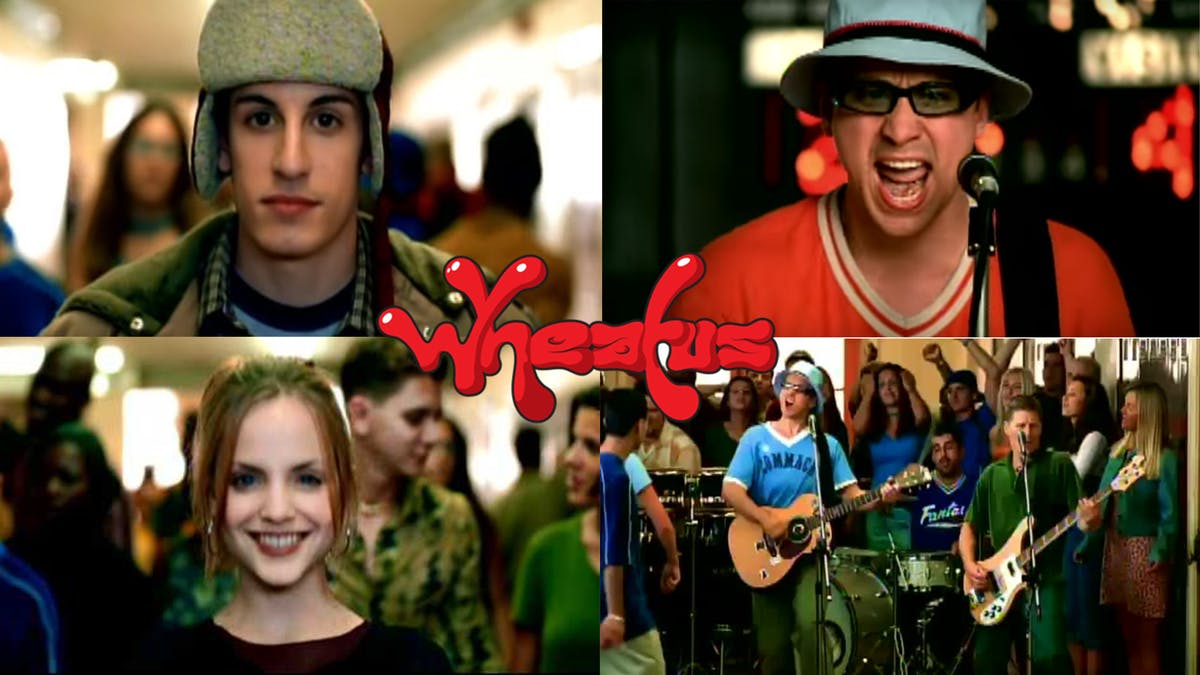

In August of this year Wheatus’ enduring cult classic “Teenage Dirtbag” turns 20. During those last two decades the song’s popularity has shown no signs of waning as it continues to reach new audiences in the digital era.

But while “Teenage Dirtbag” still generates a decent amount of yearly income (lead singer and songwriter Brendan Brown compared it to “owning a deli” in a recent Rolling Stone interview), there is one issue that has plagued the band for years and prevented them from monetising the song to its full potential: they do not own or even have access to the master recording.

This has led Brendan Brown and his band to embark on an ambitious re-recording project to recreate not just “Teenage Dirtbag”, but their entire debut album with the goal of releasing a 20th anniversary edition later this year.

To learn more we chatted to Brown about this daunting endeavour and his plans for the future of the pop rock anthem.

First of all, how did the masters go missing?

I had sent the last full set of the master tapes to Sony Music, our record label at the time. The format was kind of shitty because we didn’t have any money when we made the record and it was all recorded on ADAT using DA-78HR machines. Then Pro Tools and Logic really came on as viable multi-tracking systems and killed every piece of hardware, making our files instantly obsolete. I knew this and I remember saying to our A&R guy, who was great but not very technical, “how are you storing it?”.

You have to keep in mind that we were a very small fish in a very big pond at Sony. They were worried about Bruce Springsteen and Bob Dylan box-sets. They weren’t concerned with my digital multitrack of 10 songs, which is fair enough. So that was the last time I saw those master tapes and we never found out where they went. We ended our deal with Sony in 2004 and since then I’ve struggled to find someone to communicate with there, so we never got an answer. I think the tapes are probably lost and if they haven’t been transferred by now, they’re definitely wasted. So it was a combination of it being a transitional time for recording technology and us not being in control of where the tapes went.

When did you first think about creating a new version of “Teenage Dirtbag”?

People from the Rock Band network reached out in 2008 because they wanted a version of “Teenage Dirtbag”. We were on and off the road so much during that time so it was really difficult to record. We took a stab at it but it didn’t really come out the right way. In 2014 I had kind of given up on getting the original set of masters so I brought the last remaining set I had, which was incomplete, to be transferred to Pro Tools. That gave us a skeletal foundation of every song on the record, but a lot was still missing.

We had sold a lot of the gear that was used to make the first record, so at that point I started recollecting it and we went through song by song trying to figure out how to match the sound and maybe even do a little bit better this time. We were extremely inexperienced when we recorded that first version at my mother’s house. Eventually we put Humpty Dumpty back together again.

What made you really focus on the re-creation project over the last year? How has the process been?

The 20th anniversary of the album release was approaching and I didn’t want to be without them anymore. It’s been hard not having something that I made that is precious to me. Re-creating these songs has been a weird, labor intensive forensic exercise. I was shocked and surprised by how intense and difficult it was to get right, and it’s not like making a new record where it’s a creative process and it gives you energy and keeps you moving forward. I wasn’t waking up in the morning like, yeah, I’m going to really nail the tambourine in “Teenage Dirtbag” today!

“Re-creating these songs has been a weird, labor intensive forensic exercise. I was shocked and surprised by how intense and difficult it was to get right.”

What were the hardest parts of “Teenage Dirtbag” to get right?

There were two very, very difficult elements. First was the keyboard sound. The keyboard lick was the only part of the song that was recorded in a studio outside of my mother’s house and we couldn’t figure out what it was. We got really into the weeds with it – there’s even a reddit thread about it. Eventually we discovered it was a version of a sample from the original DTMF bell telephone system and from there it took us nine full days to build a patch that worked. Our keyboard player Brandon Ticer had the patience and intuition to find out what the original source was and together we reconstructed it. So that was really tricky, but we got that.

And then there was this weird artifact. “Teenage Dirtbag” has six guitar tracks layered very densely and one of them was recorded earlier on in the process when we didn’t really know what we were doing. I only used the acoustic guitar on that record and I was standing in front of the speakers and they were just blaring right into the top of my guitar. This turned the guitar top into somewhat of a microphone, so every time the snare hit, and this was the original demo drums which were fake, the sound was bleeding right down my guitar channel. It made this sort of echo artifact of snare but processed through the guitar sound on only the left side of the song.

We sat for hours listening to the original mix wondering what that little flash was that was making the drums a little more stereo in the chorus, and eventually we figured it out. Going into this project I really thought that we’d just do it good a second time. But there were all these strange twists in the road and things that we had to trace back. But it worked. We actually tricked YouTube’s algorithm with the 2020 version, which we premiered last month, because we got a Sony Music copyright notification that we’re currently disputing. So we really must have come close!

How have sync placements helped to keep the song in the public eye? Do you notice their impact?

It has ticked up in the last few years. I guess “Teenage Dirtbag” is more or less a collect part of the fabric of some people’s musical experience now. It’s passed into this other phase of being out there. But initially, because the multitracks didn’t exist, it was never in Guitar Hero or Rock Band. For the most part the syncs on the master side have been pretty selective and sparse. The publishing syncs for covers and other versions have kind of gone off the charts – I think One Direction really kicked that off, and we also had the placement in Generation Kill. But I think a bit of scarcity has helped it along slightly.

“We haven’t had a manager or record label since 2005. So whatever it’s done in the sync world since then, it’s done on its own really. It’s earned its own keep.”

It’s never really had a champion, you know. It’s one of those songs that predated the internet and then had a bit of a landing into the internet once it really kicked off. We haven’t had a manager or record label since 2005. So whatever it’s done in the sync world since then, it’s done on its own really. It’s earned its own keep.

Now that you own and control the masters there will surely be more opportunities for monetisation?

Yeah. That would be nice if those things come in, but ultimately I was really not comfortable with the fact that we didn’t have this thing that we worked on. It took me from 1995 until the spring of 2000 to get those songs right and to figure out how “Teenage Dirtbag” was supposed to sound, and that vanished from me. Interestingly, the original digital masters don’t line up with what you hear on Spotify or Apple Music because it was all mixed down to half inch tape and tape stretches a bit. So even the digital artifact isn’t correct and I can’t access it if I wanted to. I wanted to do away with all of that and to get it right again while we still can, and to possess this thing that we have the right to possess. This thing that was ours to begin with. So it’s a reclamation more than it is a marketing move.

“I wanted to possess this thing that we have the right to possess. This thing that was ours to begin with. So it’s a reclamation more than it is a marketing move.”

What are your plans for the 20th anniversary album release?

We had a ton of touring plans and we still have some, although I can’t speak to whether or not they’re going to happen. We’re going to release the 20 song 20th anniversary edition of our first album sometime later this year, probably in August. The original record had 10 songs on it but for the new edition we’ve added 10 songs from over the years that felt very first album-ish. It feels like the exploded version of our first album. And we’ll have all the multi-tracks, the instrumentals, the acapellas, and all the stuff we need moving forward

We’ve also decided to future proof our masters by recording them in direct streaming digital (DSD). It’s a 1-bit format that records at 11.2 megahertz which is even more resolute than original analog tape. We’ll be cutting the vinyl version straight off of DSD, so I’m really excited about that. We got stung by the obsolete format thing the first time we did this and now we’re making sure that it doesn’t happen again!

Never again!

Exactly. This is the last time. Never again!

How will it work when you release the tracks on digital platforms? Won’t you be competing with the original versions?

We went over this a lot and we thought, how do we do it? How do we name it? And we just thought it’s gotta be “Teenage Dirtbag 2020”. Every other song is going to have that 2020 tag in the metadata so there’s no confusion. There’s no way to get around the fact that we’ll be competing with the original masters usage, but it’s also a different thing entirely. Plus the original masters are unavailable in multi-track or acapella or instrumental. So there’s not much to compete with there.

You recently launched the Quaranteenage Dirtbag Challenge. Can you tell us a bit more about that?

Oh man, talk about unforeseen consequences! Joey Slater, one of our backing vocalists, had this great idea to ask people to make videos of themselves playing/singing along to “Teenage Dirtbag” for one mass quarantine video. The next thing we know it kind of blew up and she and our bass player Matthew have been neck deep in editing hundreds of submissions. It’s become a bigger thing than we ever thought it would be and we’re so grateful to everyone who shared their time and talents with us.

“The author’s intentions are not that important in the end – what it means to other people is the key to its survival and longevity.”

Has “Teenage Dirtbag” become a bigger thing than you ever thought it would be?

Yes. In some ways, things like masters ownership and sync rights don’t matter. It’s not really mine anymore anyway – the public owns it and whatever it meant to me when I wrote it has kind of become irrelevant. The author’s intentions are not that important in the end – what it means to other people is the key to its survival and longevity.

Enjoyed this article? Why not check out:

- Over and Over: How the Digital Song Economy is Generating Hit After Hit

- For the (Re-)Record: Here’s What You Need to Know About Re-Recording Restrictions

- Copyright Terminations: What Music Rightsholders Need to Know