There are six stages of a crisis. It starts with a warning and then moves through risk assessment, response, management, resolution and finally into recovery. With the global pandemic, all parts of the music business (and, indeed, most other businesses) were shunted very quickly through stages one and two and straight into the middle of stage three, having little warning and being forced to start to develop a response before even a full risk assessment could be undertaken.

In that sense, everyone was having to simultaneously work backwards (to assess the risks without the advantage of a long warning) and forwards (to figure out a response that leads eventually to recovery).

PROs under pressure

The initial reaction from the PROs and publishers was to set up hardship funds for members they knew were going to be badly hit immediately as concerts, tours and festivals got pulled. What bodies like PRS, PPL, SOCAN and GEMA all did in those early stages is typical of what happened among other organisations, with government aid eventually being offered and huge donations being pledged to the likes of MusiCares.

While this money was all welcome and necessary, it soon became clear that it was like throwing a sponge at Niagara Falls. The problem was only gathering velocity and long-term plans and whole new thinking were having to be created and implemented on the hoof.

Bad news came in the shape of ASCAP announcing that royalty distributions to members originally scheduled for 6th April were being bumped by just over three weeks to 28th April. “This is because we had to go through a collection cycle of March 31/April 1 payment due dates to determine accurate cash flow before finalising the funding pool and processing hundreds of thousands of distribution files for payment processing services,” explained CEO Beth Matthews. “Some of the vendor services we use to process and pay the distributions have also been materially impacted by COVID-19, so there is a domino impact that we are constantly navigating in terms of ensuring business continuity.”

Thankfully this temporary logjam was to be the exception rather than the rule as other societies and organisations looked instead to speed up payments to members. BMI, swiftly following the ASCAP announcement, contacted members to assure them that “our goal is to minimize its financial impact on you” and that its royalty distributions “will not be affected by the pandemic in the near future”.

From there, the enormity of the situation became such that it was starting to block out the sun and unprecedented steps had to be taken, such as PPL in April bringing forward part of its June distribution. Of course, despite the magnanimous nature of the gesture, this was only going to delay the inevitable and its next wave of payments will be lower just as the harshness of the economic reality really hits for musicians as the fecund European festival season was cancelled.

Performing rights revenue hit hard

The live industry is unquestionably taking the biggest hit, with the Association of Independent Festivals reporting that 92% of its members fear they could be at risk of going out of business due to a summer of cancellations.

The fact that performing rights revenue from these events has also evaporated completely means that a major part of songwriters’ summer income has disappeared.

“Live music has effectively been shut down for the foreseeable future,” says Virginie Berger, founder of Paris-based agency DBTH. “For musicians who see a significant portion of their income during the summer and fall months as festival season gets into full swing, the situation is existential. Seemingly overnight, a once-depended-on revenue stream has been cut, with no signs of relief on the horizon.”

“The effects, especially on performance revenues, may not therefore be visible for a long time and will take several future distributions in order to be able to assess impact.”

– Virginie Berger, DBTH

The impact here, she says, will really be felt much later in the year or next year when payments from the summer start to make their way through to writers. “The effects, especially on performance revenues, may not therefore be visible for a long time and will take several future distributions in order to be able to assess impact,” she says.

It is worth noting, of course, that not all payments are typically made with a long delay and that advances and loans – things that were a last resort option for some facing hard times – could become much more commonplace as writers look to keep the lights on. For now, at least.

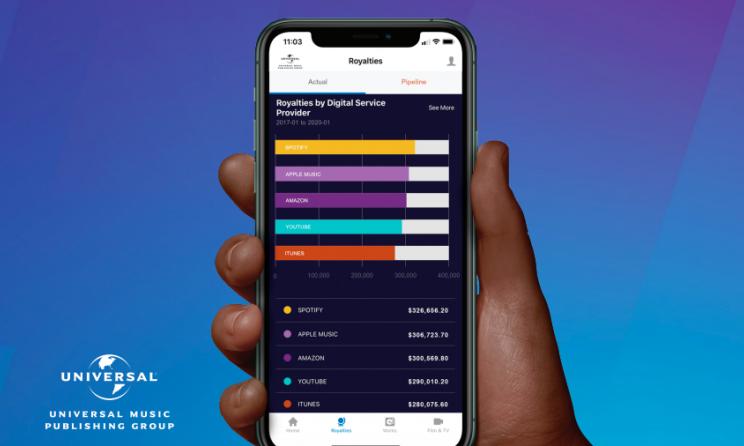

Arriving just before the pandemic hit, Universal Music Publishing Group’s new payment portal offered writers advances on future earnings. “Building on its popular one-click advance feature, UMPG Window now offers the unique ability for clients to request no-fee advances based on both current period earnings and international pipeline earnings,” said the publisher on introducing the app.”

Buffering the impact of the pandemic was clearly not its initial intention, but all lifelines have to be grabbed at in a crisis.

Livestreams won’t pay the bills

The immediate response to live shows being cancelled was to fill the vacuum with livestreams – in part to scratch the itch for fans denied a summer of outdoor music but also to keep acts front and centre in the public’s consciousness. A few artists, like Laura Marling, have experimented with charging for them and limiting the number of tickets available to create a sense of scarcity, but most of them happen for free.

Yet there are, from a rights perspective, significant problems tied up with livestreams happening at all.

As business writer Cherie Hu notes in a piece exploring the labyrinthine rights issues here, it cannot be presumed that a livestream is actually licensed (and, as such, its royalties flow back to writers).

“While the likes of Facebook, Instagram and YouTube have licensing deals in place with major rights holders, which should technically free individual users from any liability around using that content, those licensing deals only cover on-demand content, not livestreamed content,” she says. “For livestreams, many of these same platforms are adopting legal language that puts liability on artists, not on themselves. The big elephant in the room with Twitch, and with its peers in the space that allow for real-time payments to streamers during live broadcasts, is that they make most of their money from these live payments, not from archival content. Because there’s no real-time claim system, none of that majority revenue is shared with music rights holders if their content is included in a high-earning stream.”

It is a point that licensing expert Deborah Mannis-Gardner also makes, suggesting it is all a ticking time bomb that the current pivot to livestreaming is exposing.

“The [main] issues that we’ve run into are platforms that are lacking licenses from performing-rights organizations,” she told Variety. “A lot of these platforms take the position that because they’re licensing third-party programming, it’s not their responsibility to get a PRO license. But it is. If they’re going to make money exploiting music, they should take the responsibility to get a PRO license.”

“A lot of these platforms take the position that because they’re licensing third-party programming, it’s not their responsibility to get a PRO license. But it is. If they’re going to make money exploiting music, they should take the responsibility to get a PRO license.”

– Deborah Mannis-Gardner, DMG Clearances

She added, “I’m sure people are going to get mad for what I’m saying to you, but we need to take into account how songwriters are being affected by bars being closed, restaurants being closed, clubs, shows, grand rights, Broadway — all that PRO revenue is gone, so if these streaming or internet platforms are not willing to get a blanket PRO license, then they don’t deserve to have music. We need to come up with ways to keep the revenue flowing.”

Or, as Berger puts it in much blunter terms, “Livestream is a great PR idea, but it won’t help rightsholders to pay their monthly rent.”

Can other royalty streams help to plug the gap?

Beyond the rights conundrum of livestreaming, there is some debate over whether or not licensing in general is going up as countries enter lockdown. As film and TV productions are being put on hold, so too are sync opportunities; but some in the business feel other licensing opportunities can help plug the gap.

Keith Bernstein, CEO and president of the Royalty Review Council, says that traditional licensed outlets (like film and TV) may be frozen for now, but other areas are stepping forward.

“In terms of licensing, in my discussion with labels and publishers, I have not heard it mentioned that license requests are down, but rather there seems to be an influx of license requests for startups. I am not sure how licensing can be materially impacted if there are attorneys, label personnel and publisher personnel able to perform their work remotely essentially as they did before,” he says.

Berger is, however, not so convinced that where one licensing door closes another opens. “Syncs and commercial broadcast are also suffering, because of the downfall of the advertising market which drives revenues from television, radio and cable and the postponing of TV and movie projects,” she says. “We hope streaming can remain at least flat for the next few months. But streaming service royalties offer a fraction of a cent every time.”

Another long-term problem is that many records were due to be recorded now with an eye on releasing them later this year or early next year – meaning that any mechanical royalties from them, when they eventually happen, will be kicked further down the road. “In the current circumstances, the recording artists are not going to be able to deliver a record, mechanical revenues are decreasing,” says Berger.

Charli XCX is that rare breed of artist who rose to the challenge and used lockdown to write, record and release a brand new album in the space of a couple of weeks, but she is very much an outlier here.

Bernstein also suggests that the delay to recordings today could be a problem for the future, and catalogue benefits in the interim.

“To the extent that recording sessions cannot fully happen right now and in-person collaboration is online, it will slow down new releases for what has not already been recorded and where the master is finished,” he says. “That creates more of a dependency on catalogue – even for movies in production where maybe an existing sound recording is selected and a new track is not written and recorded for the movie.”

The streaming royalties debate gets reignited

This looming crisis in mechanicals has seen a renewed call for more money from streaming services to be paid through to creators, with the #BrokenRecord movement in the UK being spearheaded by Tom Gray from Gomez (as well as being on the boards of PRS for Music and the Ivors Academy). He suggested that streaming services increase their prices by 25% (so, for example, £12.50 a month as opposed to £9.99) in order to pay writers and recording artists a bigger share than they already get.

In an op-ed for God Is In The TV, he wrote about DSP and label resistance to subscription increases, “Stop saying it’s price-sensitive; Kids pay £8 for a skin in Fortnite and we can’t ask for £12.50 for the entirety of all recorded music? Give me a break.”

This is, on paper at least, an appealing idea. Yet, as Stuart Dredge of Music Ally – in a very detailed and balanced dissection of all the debates here – noted, it’s going to be incredibly difficult to get the industry as a whole moving together on this one. The pandemic, however, has brought the issue to the fore again and #BrokenRecord is lobbying hard to get the industry to change and to not waste this opportunity for the debate to be heard in public.

One thing is clear, income for writers is going to be significantly down in 2020 and the economic impact will not be felt fully until 2021 or even 2022.

One thing is clear, income for writers is going to be significantly down in 2020 and the economic impact will not be felt fully until 2021 or even 2022. Already, collecting societies are caveating record-breaking revenues being reported in 2019 with the stark warning that 2020 will see a drop. It is not a question of if the drop will happen but rather of when and how vertiginous it will be.

“With TV and film productions on hold, closure of businesses, public premises, and the cancellation of festivals, concerts and other live music events, we will inevitably see a decline in future royalties in 2020 and into 2021,” said PRS for Music’s CEO Andrea Martin in mid May on publishing its payment numbers for 2019. “We expect the most significant impact will be on our public performance business and the royalties we collect internationally, but at this stage the exact financial impact, and how this will affect individual members, is extremely difficult to fully predict.”

This is when the second wave of financial problems will crash down around us. Accelerating advances on past performances and licences is not getting more money to writers; it is just getting money they are already owed to them quicker. The “robbing Peter to pay Paul” strategy offers short-term relief but it cannot ward off long-term pain.

The likes of Royalty Advance, Sound Royalties and Lyric Financial have stepped forward here by offering loans. This is both good and bad as it is money now, but no one knows when things will eventually stabilise and how long it will take people to clear a loan. As Rolling Stone found out when it investigated what companies here were doing, they “were reluctant to talk about their specific approval criteria and repayment programs”.

One positive, however, is that publishers are still signing deals (even if labels are slowing down their signings) meaning that the lifeblood of the industry continues to flow. These are writers who might not start to make an impact for a few years as they build their profiles and expand their portfolio, but the fact that deals are still happening means that the ascendancy of new writers a few years down the line should still happen.

Proceeding with caution

Bernstein points to a macro concern in the sector that licensing partners could actually – fearful for their own longevity here – slow down or withhold payments to rightsowners and collecting societies. It is a dystopian thought, but it could happen.

“I hope it is not the case and I hope that people are honest with earnings payable, but if licensees have a drop in cash flow and there are royalties sitting in reserves or accrued to be paid, it’s possible that companies could hold back on making 100% of earnings payable to a label, publisher or PRO right now and use the cash for their operations if they become desperate,” he warns. “Plus, if there is a drop in royalties paid by a licensee it will be difficult – without an audit – to know if the drop is fully attributed to the pandemic. I am talking about the companies who license the music from the labels, publishers and PROs.”

“I hope it is not the case and I hope that people are honest with earnings payable, but if licensees have a drop in cash flow and there are royalties sitting in reserves or accrued to be paid, it’s possible that companies could hold back on making 100% of earnings payable to a label, publisher or PRO right now.”

– Keith Bernstein, Royalty Review Council

He also cautions that songwriters need to keep a sharp eye on their earnings and demand an audit of their royalties early next year when the impact will be more clearly spelt out in black and white on earnings spreadsheets.

“I think you need to watch subscriber counts on streaming services for a drop in the number of paid subscribers – and maybe you can have a reasonableness check to assess the percentage drop in streaming subscribers, if any, to a percentage drop in your earnings,” he says. “I think people should review their statements and compare earnings after March 1, 2020 to the same periods in 2019 and simply ask themselves if any drop in earnings makes sense. Overall, if you have an audit right, it’s probably a good idea to consider an audit around the end of Q1 2021 if your earnings have dropped materially – [you should do it] after Q1 2021 because you want all of the 2020 statements to be rendered before you start an audit.”

Tied to this, Berger says that PROs, publishers and others have a responsibility to understand how cash flow needs to be recalibrated given the earnings drop that is coming.

“Companies should look carefully at their financial planning for the next 12 months and beyond with a view to managing cashflow,” she recommends. “This is especially important for companies whose performance payments make up a significant proportion of their overall revenues, but who have not yet seen any immediate impact of the crisis at this early stage. These companies should work with their banks, accountants, investors, partners and intermediaries in order to implement safety measures to manage significant drops in income for a long period.”

“Companies should look carefully at their financial planning for the next 12 months and beyond with a view to managing cashflow.”

– Virginie Berger, DBTH

A sign of things to come

Giving writers advances on future payments or paying monies out faster is a temporary solution – but it could also actually change the royalties business of the future. PRS for Music, Universal Music Publishing and Kobalt are among the companies pushing apps and dashboards to writers to show them in granular detail and also in (almost) real time precisely what they are earning. They have the data, writers will argue, so why are we still waiting months to get paid? In an age of real-time analytics, there will be growing calls for real-time payments across the board. Bodies and companies have the technology to do it and, when we come out the other side of this, writers will push for this to become standard practice and not just something wheeled out in response to emergencies. This could become the “new normal” for payments.

With so many companies, albeit with some furloughed staff, being so quick and nimble to adapt to a professional culture of working from home and Zoom meetings, this is the thing that could really reshape the music business in a post-covid world when offices finally re-open – but open in a very different way.

The Financial Times has a fascinating piece on how the pandemic could make the idea of the office – and all staff being there for nine hours a day, five days a week – a total anachronism. There is a cost-saving here as companies cut back on jaw-droppingly expensive office spaces in major cities like London, New York, Tokyo, Sydney, Stockholm and Berlin; but there is also a human benefit as staff will start to demand greater flexibility and a limit on their commuting time, pointing to the fact they were able to do their jobs as normal while working from makeshift offices in their kitchens (even if they also had to home school their children at the same time).

This could see music organisations work leaner and lower their overheads which should, in theory, see more money going to writers. As Larry Mestel of Primary Wave told Billboard, “It’s been actually eye-opening how much more focused we are as a team because there are no intermittent interruptions of people coming over to your desk or your office, there’s no staff going out for lunch during the day. I think we’ve been as productive as we’ve ever been and we’ve actually decided we’re going to change our office environment.”

He elaborated, “Right now, our office in LA is somewhere around 12,000 square feet. Why not have a better, more creative space with fewer offices with 7,000 square feet? I certainly think people are going to be thinking twice about how they work. The transition’s been seamless and incredibly efficient for us. We’re happy with it.”

If there is to be one silver lining here it is that the business becomes leaner, faster, more efficient and more humane.

The music industry will emerge out of this battered and bruised. No question. There is no point trying to sugar coat this. It will be a painful time for all, especially writers and performers. But if there is to be one silver lining here it is that the business becomes leaner, faster, more efficient and more humane.

It is clearly horrifying that it has taken a pandemic to show the industry what it can do when all the old certainties and routines have to be abandoned; but as it adapts to the crisis and shows what it is capable of under duress, the benefits of these new ways of working will become expected. The unusual will become the usual.

The music industry has found itself in the maw of a crisis, but in fighting against the odds it has had to invent (or, in some cases, just simply accept) the materials that will build it a new and better future.

Found this article useful? Why not check out:

- Looking to Monetized Music Platforms in a Pandemic – Part 1

- We Built This City: How are the Music Industry and Sync Community Mobilising to Combat Coronavirus?

- Lockdown – But Not Out: How Music Publishers Are Responding to the Coronavirus Crisis

- Everything You Need to Know About Music Publishing Royalty Audits

7 comments

Nice writing methdology helps a lot understanding trends of music during lockdonwn.

[…] https://www.synchtank.com/blog/the-situation-is-existential-music-royalties-in-a-pandemic/ […]

[…] were hit hard during the pandemic and there were various responses to help them out, but something long-term is essential to help them properly return to […]

[…] were hit hard during the pandemic and there were various responses to help them out, but something long-term is essential to help them properly return to […]

[…] were hit hard during the pandemic and there were various responses to help them out, but something long-term is essential to help them properly return to […]

[…] have been hit exhausting through the pandemic and there have been numerous responses to assist them out, however one thing long-term is important to assist them correctly return to […]

[…] as you might have guessed, performance revenues have been hit hard due to […]