A recent blog post reporting that old songs now represent 70% of the US music market has prompted both debate and incredulity. Ben Gilbert explores how this could impact the success of new talent across an evolving industry.

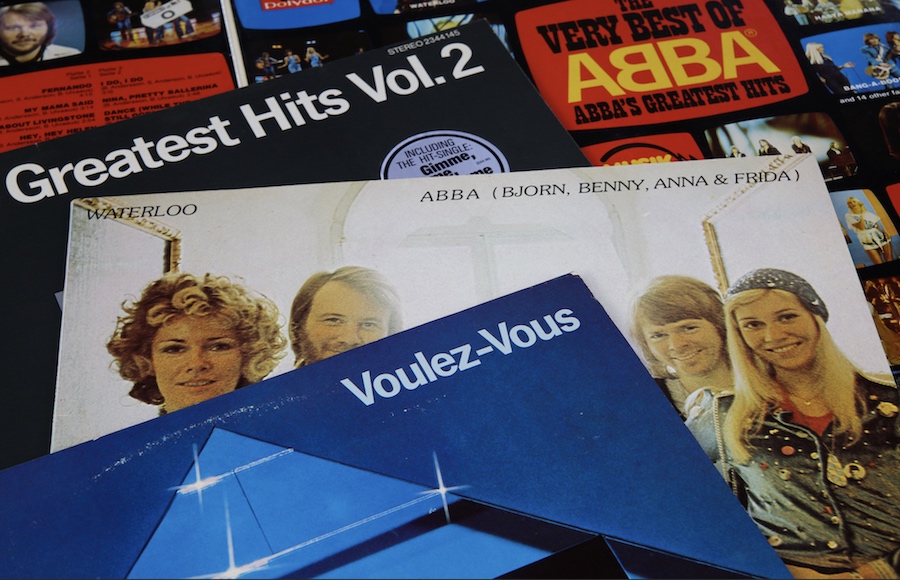

The virtual return of ABBA to their “1979 prime” will be arguably the most compelling component of the Swedish pop act’s reinvention on the live stage in London later this year. The creators of the Voyage production say they are “blending the boundary between the digital world and the physical world”, showcasing the quartet’s first new album since 1981’s The Visitors via the technical bravura within their reimagination as “ABBAtars”.

Few comparable groups can expect their musical and cultural legacy to endure towards the half century mark. “We knew that they were popular in the world,” show producer Ludvig Andersson, son of ABBA songwriter Benny, told Dazed of their comeback, continuing: “But the reaction that they got was extraordinary.” However, it’s worth pointing out that the band’s unexpected emergence from pop hibernation comes at a time when music from the past has never been so popular or powerful.

In a post that has prompted an equal measure of debate and incredulity across the music industry and beyond, Ted Gioia, writing on his Substack newsletter The Honest Broker, stated: “Old songs now represent 70% of the US music market. Even worse: The new music market is actually shrinking.” Citing statistical evidence from MRC Data, he explained: “Just consider these facts: the 200 most popular tracks now account for less than 5% of total streams. It was twice that rate just three years ago.

“Never before in history have new tracks attained hit status while generating so little cultural impact.”

– Ted Gioia

“The reasons are complex – more than just the appeal of old tunes – but the end result is unmistakable: Never before in history have new tracks attained hit status while generating so little cultural impact. In fact, the audience seems to be embracing en masse the hits of decades past. Success was always short-lived in the music business, but now it hardly makes a ripple on the attention spans of the mass market,” commented Gioia.

Today’s hits designed to blend “into the background of our lives”

Making comparisons with Erik Satie’s concept of “furniture music”, he suggested that the hits of today are designed to blend “seamlessly into the background of our lives”. Meanwhile, these existences are actually being more meaningfully soundtracked by music made many years, if not decades, ago. In emphasising this point, Music Business Worldwide cite 2015 as “a historic moment”, writing at the time: “It was the first year in living memory in which catalog album sales overtook those of ‘current’ releases.”

Naturally, this phenomenon requires some reflection and explanation. Can it, at least partially, be explained by our listening habits during the COVID-19 lockdowns and a desire for audio that provides a semblance of comfort? Equally, it’s certainly true that many big name acts have held back new material during the pandemic to ensure it will ultimately benefit from fitting promotion. Might this situation be pinned on The Song Economy and the constant regurgitation of old hits on social media? It also seems apparent that streaming services like Spotify have cemented a greater focus on individual songs rather than artists.

Kriss Thakrar, consultant at MIDiA Research, believes the answer is connected to both technology and demographics. “The audiences of streaming platforms are getting older. Most of the early adoption was from millennials who are now in their late 20s and 30s. There are twice as many people over the age of 35 as there are under 25 on streaming so the listening habits will naturally skew towards older music, coupled with younger listeners also being inclined to listen to older songs,” he told Synchtank.

“However, millennials remain Spotify’s core audience and music from this millennium (but still over two plus years old) forms the vast majority of music consumption. With catalog forming the majority of consumption on streaming, it is no wonder that the owners of that catalog are set to benefit the most. This creates new opportunities for older artists to monetise their catalog and overall it works well for labels and publishers,” commented Thakrar.

Investment in catalog material from legacy acts hit $5b in 2021

Indeed, as Gioia pointed out in a follow up post and during a TV interview with NBC, the overarching industry trend is investment in catalog material from legacy acts. “Last year, companies spent $5b buying the rights to old music,” he outlined in reference to the deals that have seen the music-based fund Hipgnosis recruit artists such as Neil Young, Fleetwood Mac and Red Hot Chili Peppers, while David Bowie, Bob Dylan, Bruce Springtseen and Sting are among the other acts to agree lucrative publishing deals in recent months.

Jonathan Larr, Entertainment & Intellectual Property Attorney at Icarus Law, believes this evolving landscape is a consequence of more sophisticated analytical tools that have accompanied the digital era. “I think the dominance of catalog is a result of record labels relying on data over artist development. A catalog has a quantifiable income stream. Developing artists is hard and unpredictable and often less profitable. However, it also leads to amazing artists who might not have gotten a chance if their careers had been driven by data.

“We would have lost out on so many amazing artists if data had ruled in the 60s and 70s the way it does today. Catalogs continue this trend because they have proven financials in a way that a new artist doesn’t. It’s not a stretch to say that the major label’s reliance on data leads to less exciting new artists which results in less people listening to new music,” Larr claimed in an interview with Synchtank.

“It’s not a stretch to say that the major label’s reliance on data leads to less exciting new artists which results in less people listening to new music.”

– Jonathan Larr, Icarus Law

In fact, it is this additional – and equally impactful – trend that’s worrying many commentators. In his original post, Gioia outlined disintegrating interest in music events such as the Grammy Awards – which has seen its audience fall from 40m in 2012 to less than 10m last year – while also pointing out that the average age of the performers at this year’s Super Bowl halftime show was 48. Adding context to this point, Thakrar admits that “new artists are at a disadvantage” when it comes to the realities of the current landscape. “They’re not only on the same channel as the entire history of recorded music but are also competing with the 60,000 plus tracks being released on streaming services every day,” he said.

Consequences for new talent described as “chilling”

It’s a point also explored by Gioia, who suggests emerging performers must now “desperately search for other ways of getting exposure”, citing licensing opportunities in advertising and TV. “But here’s the problem – these options might generate some royalty income, but do little to build name recognition,” he wrote. Dan Fowler, music and crypto strategist, agrees it is “getting harder and harder” for new artists to build significant momentum around their own careers.

“If catalog effectively ringfences a relatively fixed market share of the value paid out by royalties and the number of creators is increasing at a far greater rate than the top line value generated by streaming, there is relatively less money to go around. This has a knock-on effect in terms of the money that rightsholders will be prepared to invest into new music,” he told Synchtank, warning that the consequences for the future of the industry could be truly profound, given that these artists will also create the catalog of the future.

“Proactively investing in new talent may make less and less sense from a pure short-medium term business perspective but this will also have a chilling effect on the overall development of our industry. Unfortunately it is somewhat of a free-rider market failure in that new talent is of course essential for the development of the industry but investment in emerging artists at an individual level is likely seeing decreasing returns within the streaming paradigm,” explained Fowler.

Clearly, this is a fundamental issue for less established songwriters. In an extensive, near forensic analysis of the economics that sit centrally here, Dave Edwards, SVP Revenue at Audiomack, said “musicians are caught in a catch-22”. Writing on his Above The API blog, he continued: “It’s easier to make music than ever before, while simultaneously being harder than ever to make a living doing so.” In the post, Edwards referenced research from Music Business Worldwide’s Tim Ingham, which found that outside the biggest names on Spotify, artists earned approximately $12 per month from the platform.

Traditional frameworks of the music industry under threat

“For years, the dim financial reality of streaming has been a foregone conclusion for many artists, with most considering the medium as supplementary income (at best) for touring, merch sales, and other revenue streams. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, however, I no longer believe this is tenable. Touring has been exposed as the precarious endeavour that it truly is – a wonderful (and lucrative) means of connecting with fans, but one exceptionally prone to disruption by events beyond any of our control,” commented Edwards.

Could this ultimately change the structure of music’s biggest companies? “Arguably it already is,” said Fowler, who cited the joint ventures between rightsholders and investment companies targeting catalog material. Ingham, meanwhile, has also questioned whether the time has come for the traditional frameworks of the music industry to be broken apart, specifically ongoing reinvestment of annual returns from catalog music into frontline A&R. He quoted Universal Music Group’s decision to spend more than half of its $8b operating income on “investments for artist development” in 2019.

“This burden of A&R outgoings significantly reduces the potential profitability, and the resultant multiple valuation, of owned music catalog like Universal’s. Therefore, if you were an activist investor in a major music company today and wanted to maximize your payday, you might encourage said music company to spin out only the most valuable part of its assets – namely, its catalog rights – and keep the signing-and-developing-new-talent part of its business completely separate,” he wrote.

“A positive response could be in accepting that new music drives a lower margin but it is essential for the future of their business. Combined with a more open attitude to experimentation for the artists that they have signed.”

– Dan Fowler

To redress the balance, Fowler called for a different approach to be contemplated by music stakeholders. “A positive response could be in accepting that new music drives a lower margin but it is essential for the future of their business. Combined with a more open attitude to experimentation for the artists that they have signed. Whereas previous models may have restricted some activity, and sought to take a share of revenue from all ventures, it may be necessary to give more freedom to artists,” he explained.

“New artists turning their back on streaming”

Thakrar believes that the priority now for acts in this position must centre on building a fanbase. He pointed to interaction with “niche communities” on digital platforms such as TikTok, Twitch and Discord. “We’re seeing new artists increasingly turning their back on streaming as a viable platform to build a fanbase. It takes an incredible amount of work for typically little financial return and an inability to directly engage and communicate with your fanbase. As a result, artists are finding more fulfilment and reward by going through other channels outside of streaming,” he commented.

“It [streaming] takes an incredible amount of work for typically little financial return and an inability to directly engage and communicate with your fanbase. As a result, artists are finding more fulfilment and reward by going through other channels outside of streaming.”

– Kriss Thakrar, MIDiA Research

In the future, this is likely to include increased proximity to the audience and their specific fanbase, while more unpredictable but potentially innovative tech developments such as NFTs and Web3 provide additional alternative economic sources. Certainly, the current model seems unable to support the precarity on which the modern music industry is built. In an era of global tumult and a catastrophically disruptive timeframe that has seen one of the few existing revenue streams for many performers near totally sacrificed to a global health emergency, a redrawing of the playing field is surely overdue.

As Gioia inadvertently points out in his post, the high-profile return of legacy acts to the pop frontline is only likely to feed this backward-facing trend. He wrote: “Adding to the nightmare, dead musicians are now coming back to life in virtual form – via holograms and deepfake music – making it all the harder for a young, living artist to compete in the marketplace.”

2 comments

Interesting article. a few points. When I ran the Music Managers Forum in the UK in the decade when streaming became established I repeatedly said that s stream is not a sale or radio play, its a stream and should be treated differently to both. The record companies however treated streams as sales and have reaped huge rewards as a result. They are only just paying royalties that don’t recoup old negative balances from decades ago.

In addition there was always massive amounts of music consumption for catalogue but it was through the medium of hard copies (vinyl, cassette and CD) being repeatedly played which of course went completely uncounted and had been monetised once when the initial sale happened. And in the USA of course the monetisation of radio play for master rights never happened whilst generating huge income for performing artists in the rest of the world.

The other mantra we proposed throughout the period as “build a fanbase and monetise it”. Too many ignored this and the record companies reaped the rewards of all the data knowledge.

Its not too late to build businesses for new acts it just has to be done in an era that the labels have taken all the spoils (again) through short term tactics that made profits for the top guys and they are now riding into the sunnset with the loot. Pretty sad.

[…] A very good question: “What does catalog’s dominance mean for the future of the music business?” […]