As part of the build-up to the inaugural National Album Day on 13th October, the Official Charts Company published a chart revealing the 10 biggest-selling (and streaming) albums in the UK. Interestingly, it skewed towards the relatively contemporaneous – with only one album from the 1960s and two from the 1970s making the top 10, while three were released in the past 12 years.

Also of note was how dominant British acts were. There were effectively seven and a half – given Fleetwood Mac are made up of British and American musicians – in the top 10, indicating a market that strongly supports local artists.

The entire thrust of National Album Day was to celebrate the album as both a creative entity and a commercial powerhouse. But the album is steadily being unpicked by a process that began (illegally) with Napster in 1999, was then followed on (legally) with iTunes in 2004 and which has reached its peak recently in an age of on-demand streaming and playlists. Against this unravelling, National Album Day is designed to focus on albums as complete bodies of work and applaud those cohesive masterpieces that only make sense played from start to finish.

But looking at how albums are actually listened to on streaming services shows a disparity between the artists’ ambitions for that album and the reality of how consumers listen (or don’t listen) to them. This also has enormous implications for the writers of the songs that make up these classic albums. In the days of CDs and LPs, they all shared equally in the mechanical royalties: so for album sales, a deep cut made as much for its writer as the blockbuster hit or hits that drew in the consumer in the first place.

“Looking at how albums are actually listened to on streaming services shows a disparity between the artists’ ambitions for that album and the reality of how consumers listen (or don’t listen) to them. This also has enormous implications for the writers of the songs that make up these classic albums.”

We have looked at the streaming performance of the 10 biggest UK albums that the OCC identified and consider how streaming is impacting on them as both creative and commercial entities. To do so, we drew on Spotify data (as it is the biggest audio streaming service globally and also makes its play data public) to see to what extent albums are being listened to as albums and how much one or two break-out tracks (amplified by inclusion on key playlists) can become the new centre of gravity for them. (We discounted expanded editions of albums as this exercise was about seeing how the original incarnation of albums fare in the streaming world.)

We then mapped this across to writer credits – taking a general approach that all named writers had an equal share in the publishing. Of course, songs – unless written by one writer – can have a distinct writer split (often the cause for long-simmering problems between those writers); not everyone splits writing credits and publishing income 50/50 like John Lennon and Paul McCartney. The problem, however, is that most writer splits are never made public and so we worked on the utopian idea that, for example, five named writers on a song all shared a 20% cut of publishing.

So what did the analysis reveal? Here are the seven key things we found.

No albums are created equal – but some are more equal than others

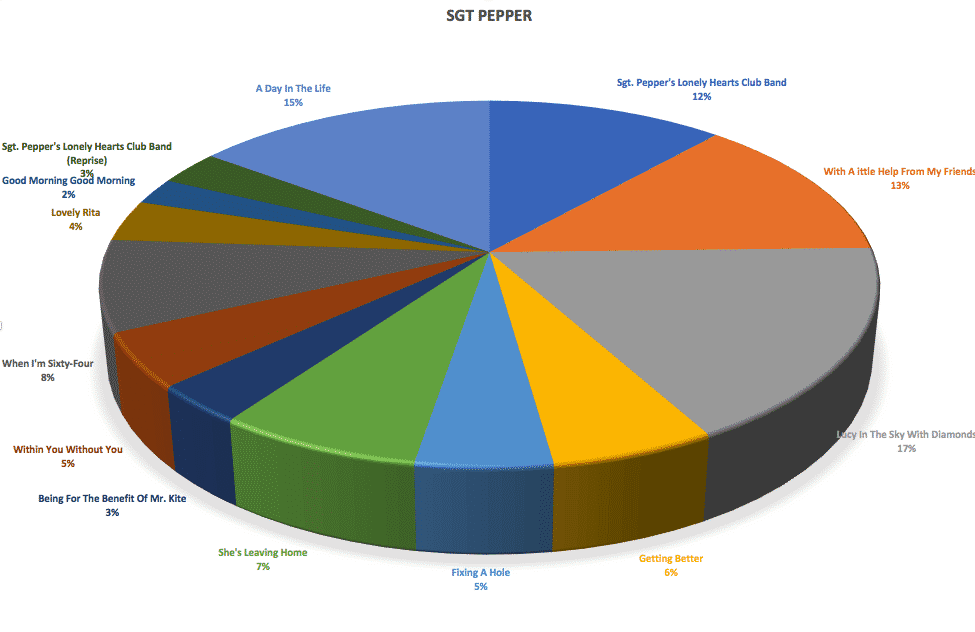

It was never going to be the case that an album’s total streams were going to be split perfectly between all the songs on that album. But only a few albums came even remotely close to having any sort of track parity. Perhaps it is fitting that the first concept album – or certainly the first concept album to really connect with the public – is the one album in the top 10 to have a relatively even split. Four tracks on Sgt Pepper… dominate (‘Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds’, ‘A Day In The Life’, ‘With A Little Help From My Friends’ and ‘Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’), but their dominance is not that pronounced. Thereafter, the other tracks are not dramatically mismatched in terms of plays – although ‘Good Morning Good Morning’ has been deemed the runt of the litter by the listening public.

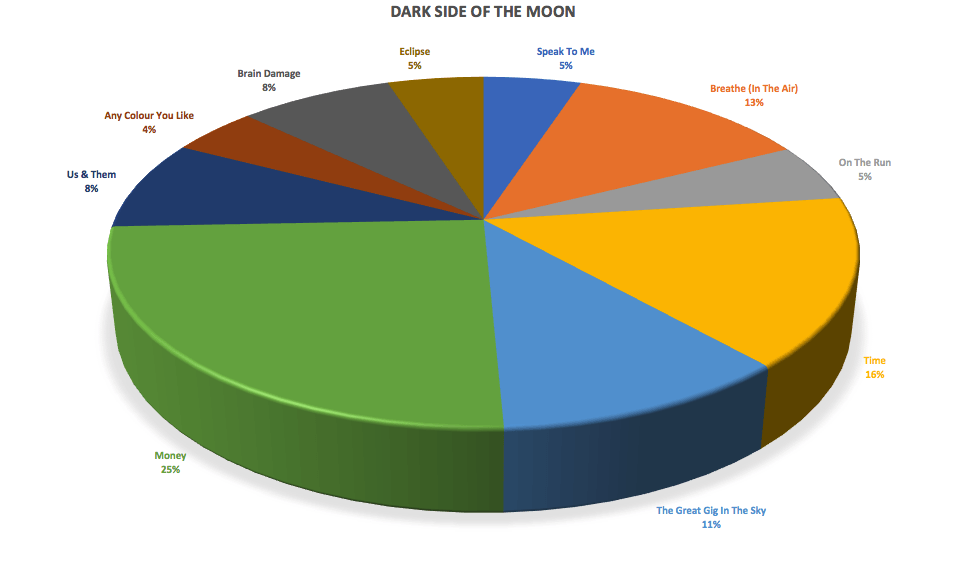

Again, it is another concept album that is next closest to having a reasonably even split. ‘Money’ is the obvious heavy hitter on Dark Side Of The Moon while ‘Time’, ‘Breathe (In The Air)’ and ‘The Great Gig In The Sky’ also over-perform, but the remaining six tracks on the album are reasonably close together in terms of their share of total album plays.

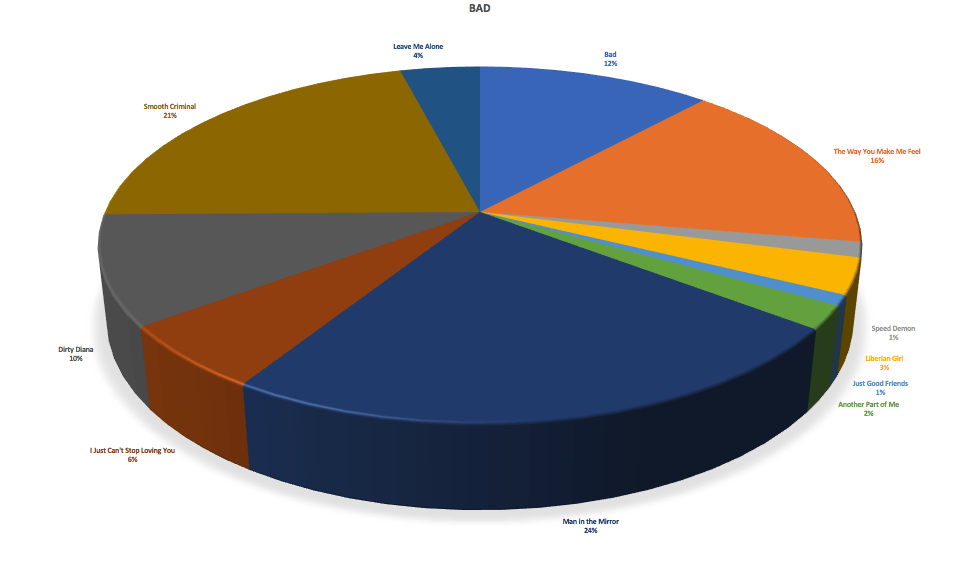

Michael Jackson’s Bad was very much a mixed bag – two huge hits in ‘Man In The Mirror’ and ‘Smooth Criminal’, then three second-tier hits in ‘Bad’, ‘The Way You Make Me Feel’ and ‘Dirty Diana’, a further two third-tier hits in ‘I Just Can’t Stop Loving You’ and ‘Leave Me Alone’ – leaving the remaining four to barely get a look in. The ones that outperform were singles at the time and thus more fixed in the public consciousness. ‘Speed Demon’ was going to be a single but was pulled and ‘Liberian Girl’ was only a single in Europe and Australia. ‘Another Part Of Me’ did not have huge impact as it was the sixth single to come from the album. And ‘Just Good Friends’, despite featuring Stevie Wonder, was always confined to being an album track.

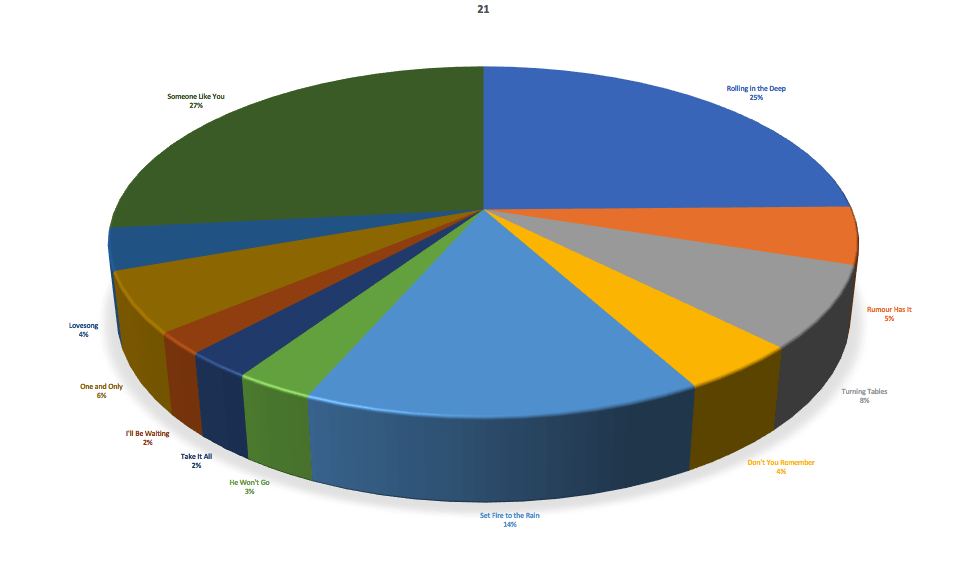

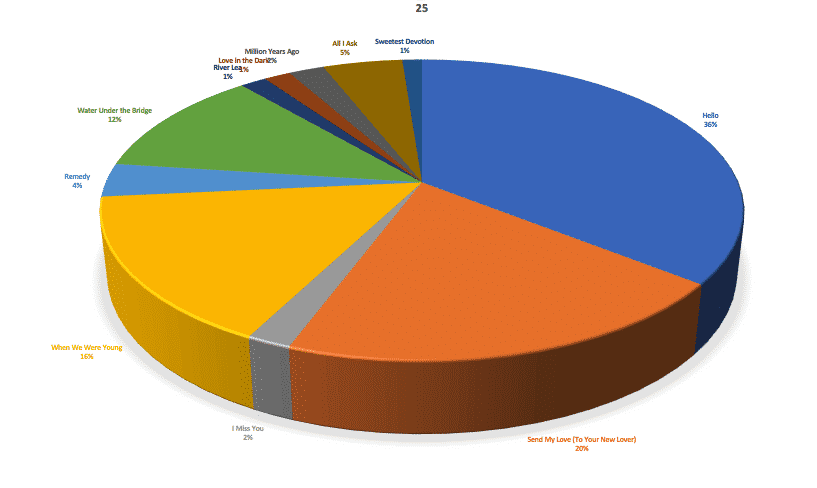

Adele’s 21 and 25 have a fascinating parallel here – three tracks on 21 and four on 25 (essential the main singles from each) dominating, but thereafter the other tracks come close to being equal. Being the two most recent albums on the list, it is perhaps an encouraging sign that listeners will investigate the whole album rather than just sticking with the big hits.

One mega-hit can tower over everything else

Three albums really stand out here for the same reason – the sheer dominance of one track, meaning the rest of the album must live in its shadow.

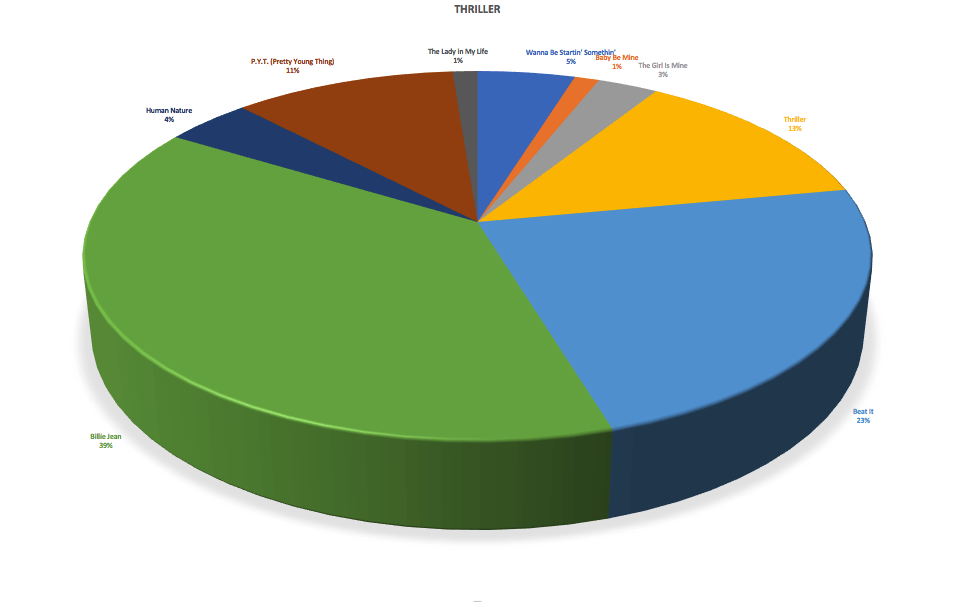

On Michael Jackson’s Thriller, ‘Billie Jean’ accounts for 39% of all the album’s streams. If we add in ‘Beat It’, those two tracks together make up almost two-thirds of the album’s streams.

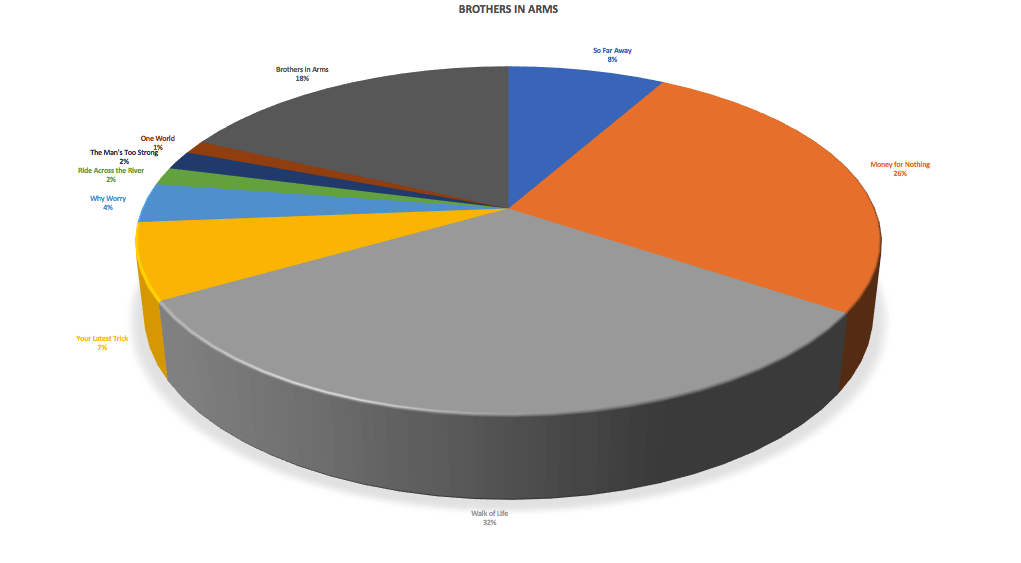

Something very similar is found on Brothers In Arms – the first big hit of the CD era – with ‘Walk Of Life’ making up just under a third of all album plays and when combined with ‘Money For Nothing’, these two tracks almost make up 60% of plays

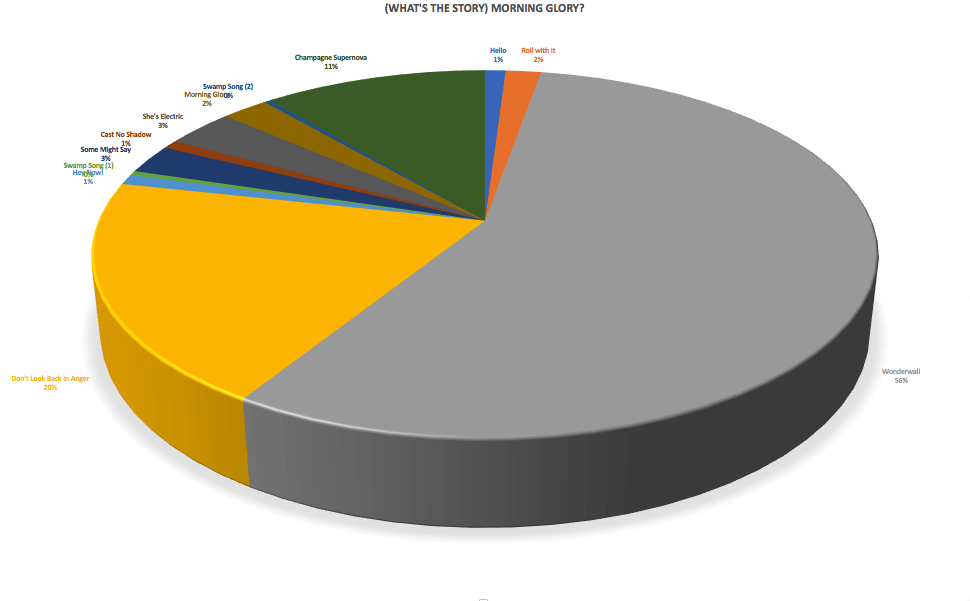

But it is (What’s The Story) Morning Glory? by Oasis that really exposes where one track is doing most of the heavy lifting. ‘Wonderwall’ commands a whopping 56% of the aggregate plays of the album. Add in ‘Don’t Look Back In Anger’ and that’s over three-quarters of the album’s streams being swallowed up by two songs. ‘Champagne Supernova’ just about manages to hold its ground against this track duopoly, but everything else on the album struggles to be noticed.

One writer tends to dominate

When it comes to writer splits on albums (and the resulting mechanicals), that is where things get really interesting.

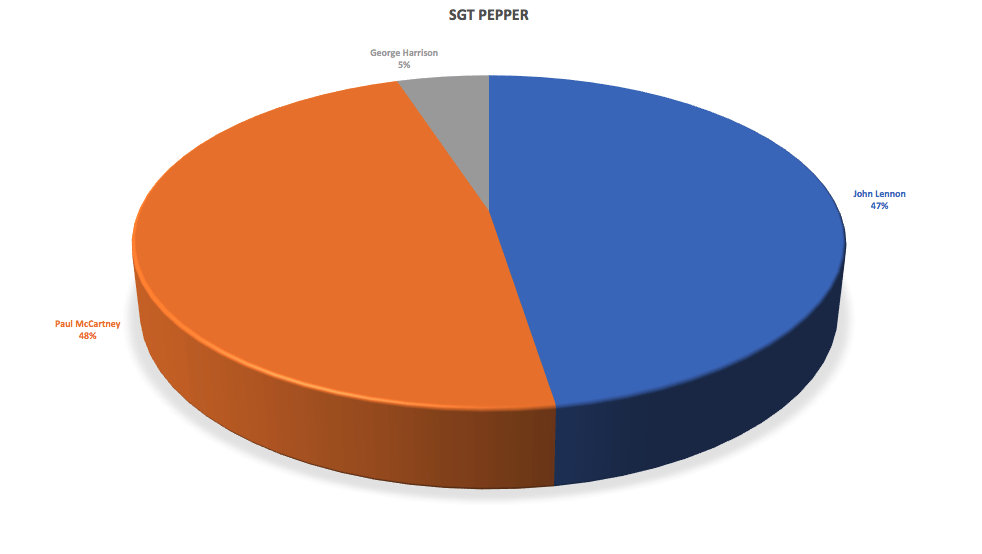

With the exception of Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours (a band at that point blessed with a variety of writers all operating at the peak of their creative powers) and The Beatles’ Sgt Pepper… (as John Lennon and Paul McCartney shared writing credits regardless of how much the other contributed to a song), one writer tends to dominate.

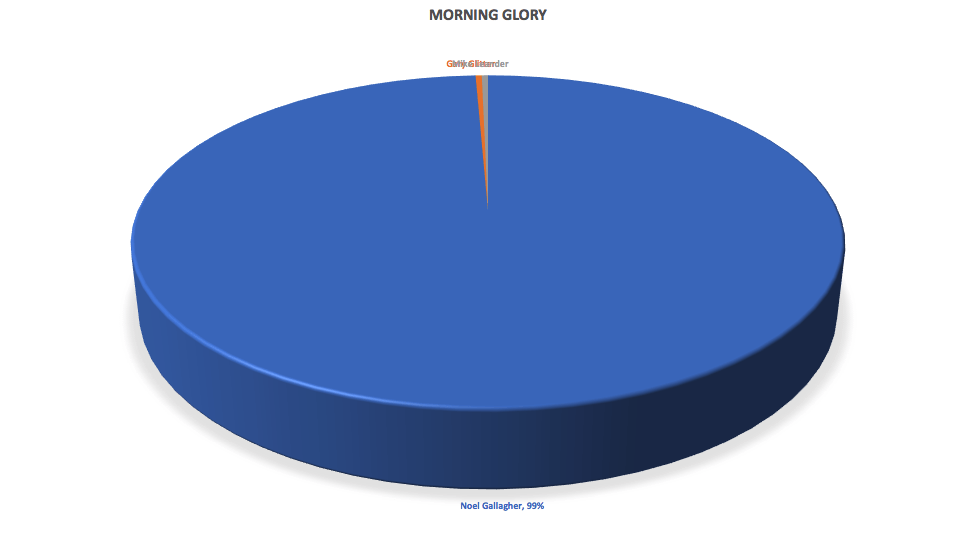

At the most extreme example, Oasis’s (What’s The Story) Morning Glory? sails very close to being entirely the writing work of Noel Gallagher. A proposed song for the album, ‘Step Out’, was pulled due to worrying similarities to Stevie Wonder’s ‘Uptight’, but the album’s opening track ‘Hello’ had to split song writing credits with Mike Leander and, more alarmingly, Gary Giltter due to lyrical lifts from Glitter’s 1973 hit ‘Hello, Hello, I’m Back Again’. If there is any positive to be salvaged from this – knowing what we know now about Glitter but didn’t know back in 1995 when the Oasis album came out – is that it is the least-streamed song from the album.

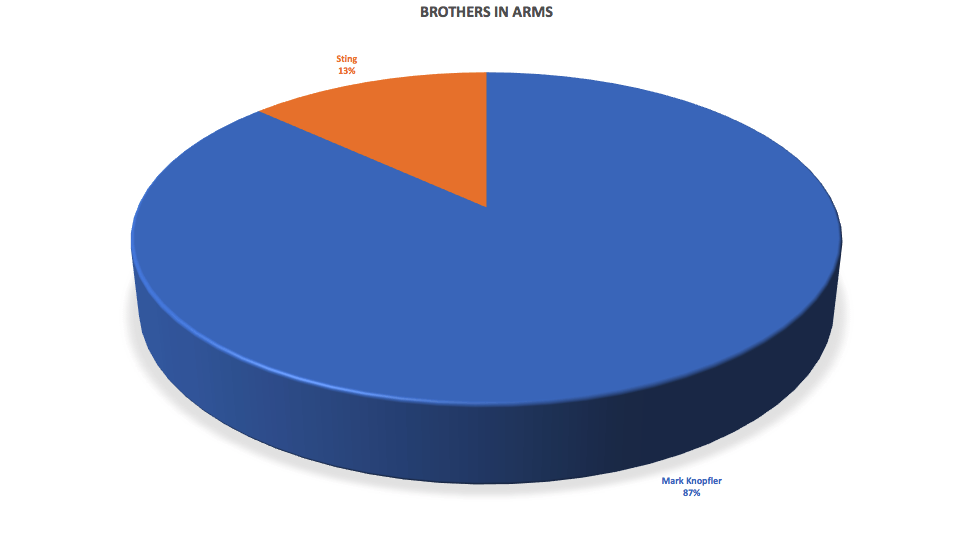

Less controversially, Mark Knopfler would have had all the writing credits on Brothers In Arms were it not for Sting co-writing ‘Money For Nothing’. Given it is the second-biggest song on the album and helped turn it into a blockbuster, it is unlikely Knopfler would be too concerned about splitting royalties on one song from the album, even if in the streaming age Sting takes a bigger cut of the album’s overall mechanicals than he would have done in the CD age.

With growing fame, the singer will up their contributions while reducing that of their co-writers…

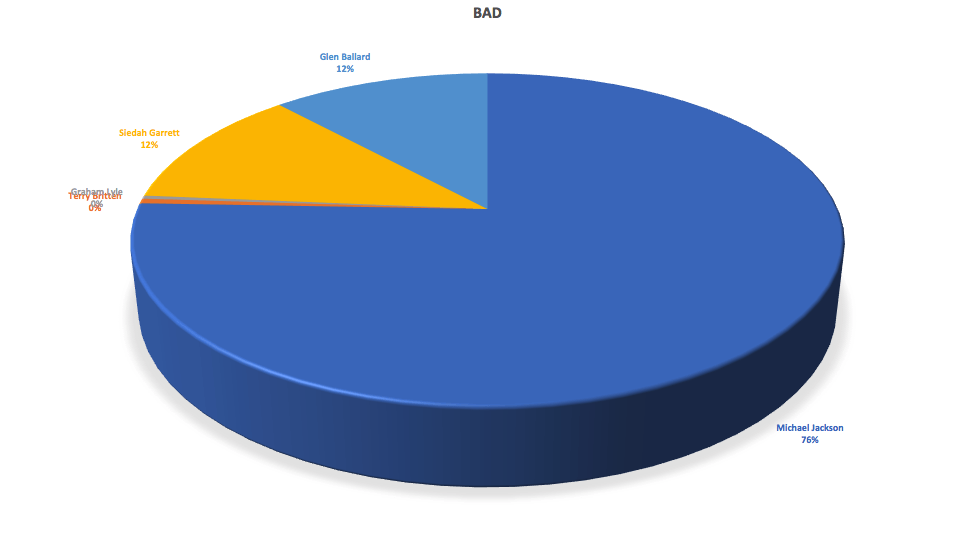

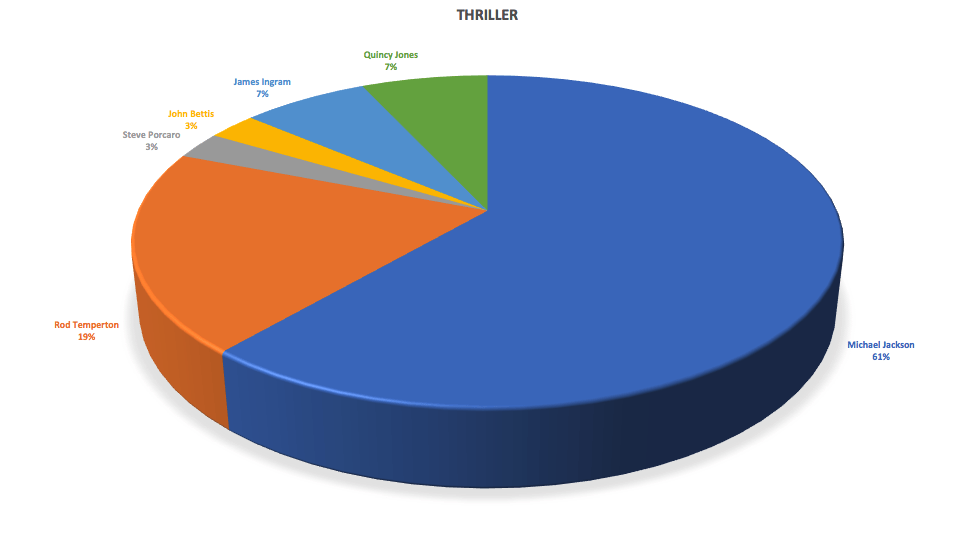

What is perhaps the most telling dynamic here is how much Michael Jackson grew as a writer between Thriller in 1982 and Bad in 1987. On the former, his writing accounts for 61% of the overall streams, with the rest being split between five other writers. But on the latter, this jumps to 76% for Jackson and there are only four other writers, with Terry Britten and Graham Lyle having written ‘Just Good Friends’, the least-streamed track on the album, accounting for a mere 1% of overall streams.

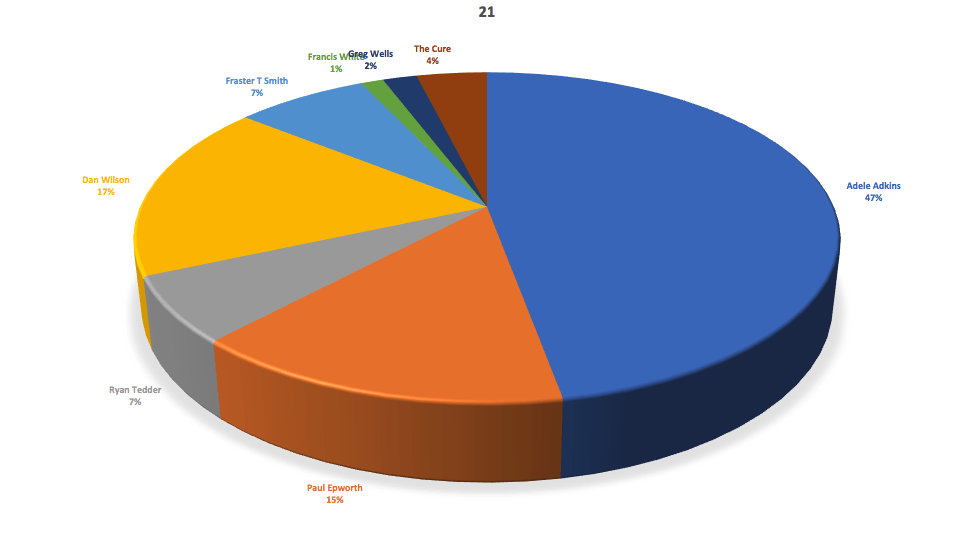

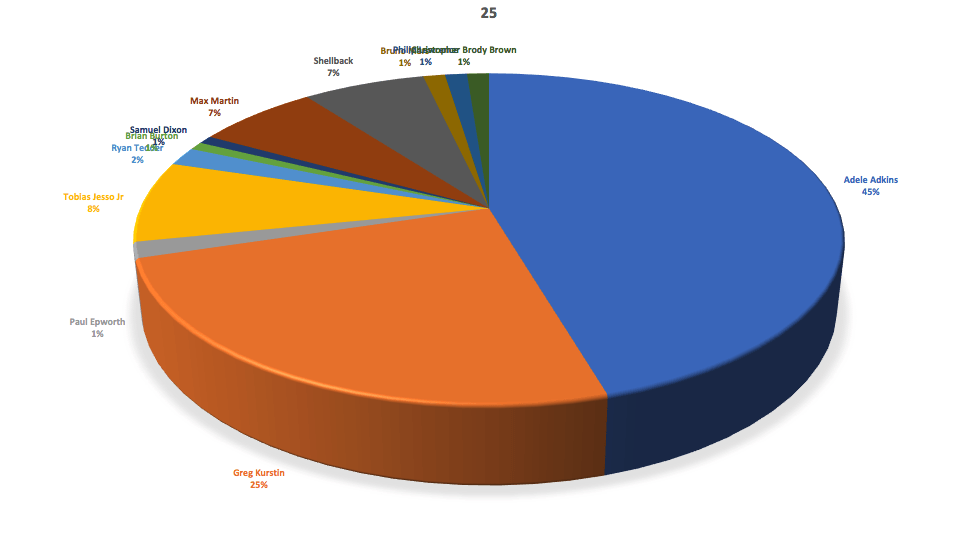

… unless they are Adele

A very different dynamic can be seen in the transition from 2011’s 21 and 2015’s 25. On 21, Adele’s share of writing accounted for 47% of total album streams and she shared writing credits with 12 other writers (bulked up considerably by the six credited writers from The Cure on ‘Lovesong’ which she covered). On 25, Adele’s writing makes up 45% of the total streams and there are 11 other listed writers across the album’s 11 songs. On 21, if we take out the members of The Cure, she had six co-writers, but this jumped to 11 on the writing for 25. So while Jackson grew his writing share while cutting down his co-writers between Thriller and Bad, Adele saw her share pretty much hold steady while her co-writers effectively doubled.

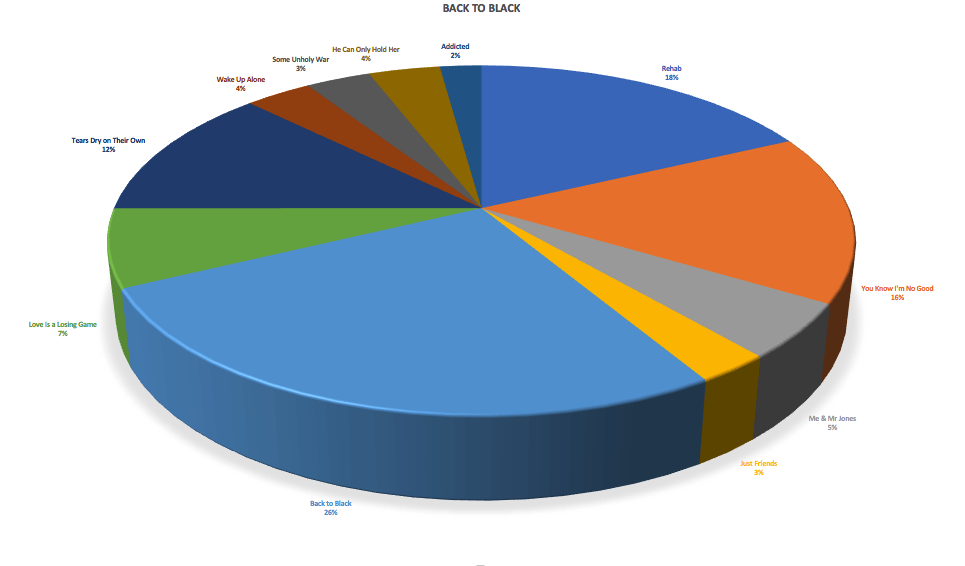

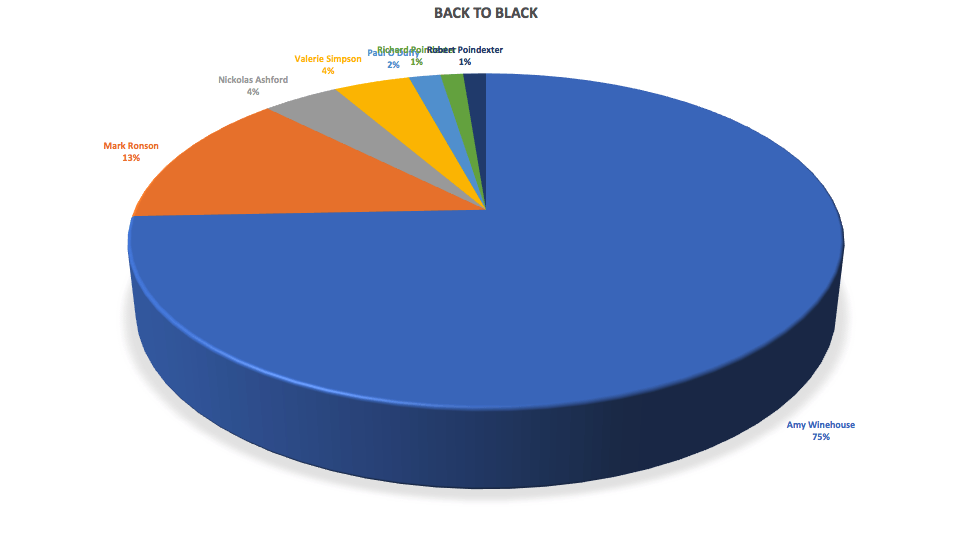

Not all collaborations are the same

On Back To Black, Amy Winehouse had six other credited writers on the album (not dissimilar to Adele on 21), but her writing dominated and her share accounts for three-quarters of total streams on the album. This is down to a very different creative dynamic to Adele. While Adele worked with at least one other writer on every song on both 21 and 25 (excluding, of course, ‘Lovesong’), Amy Winehouse was much more of an auteur. Of the album’s 11 tracks, Winehouse wrote seven of the songs on her own, only splitting credits on the album’s title track (with Mark Ronson), on ‘Tears Dry On Their Own’ (with Nickolas Ashford and Valerie Simpson, due to a sample interpolation of ‘Ain’t No Mountain High Enough’), on ‘Wake Up Alone’ (with Paul O’Duffy) and on ‘He Can Only Hold Her’ (with Richard Poindexter and Robert Poindexter).

Bands can sometimes approach parity… for some members

Noel Gallagher was the writing force behind the first three Oasis albums (it was only from 2000’s Standing On The Shoulder Of Giants that other band members started to get writing credits); Mark Knopfler dominated Brothers In Arms; George Harrison was the only other member of The Beatles beyond Lennon and McCartney to be allowed a song on Sgt Pepper…; but other bands could be seen to be getting close to sharing the writing. But not all members were granted the same equivalence.

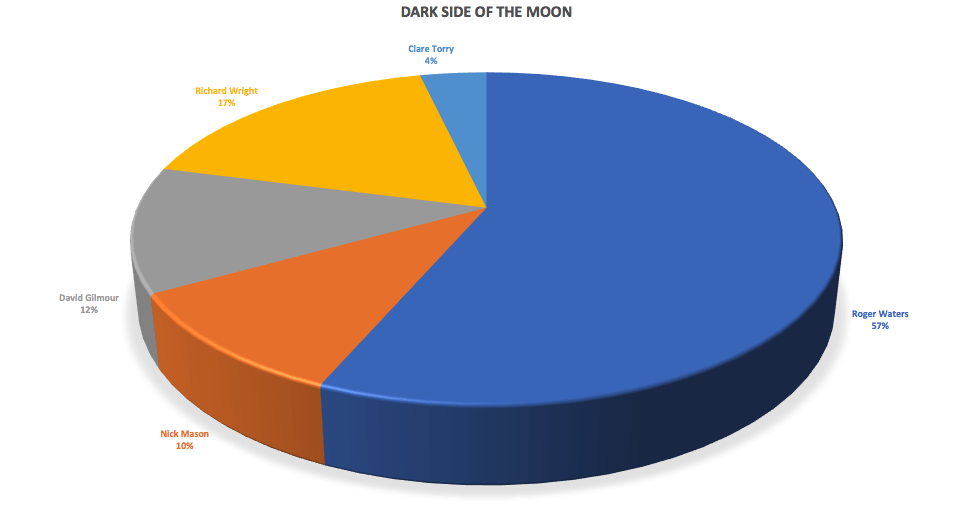

Roger Waters dominates on Dark Side Of The Moon, in a large part due to the fact he was the primary lyricist, but the other members (and Clare Torry, due to a co-write on ‘The Great Gig In The Sky’) did have reasonable writing involvement. This was, however, to change as Waters increased his writing share over subsequent albums. Dark Side Of The Moon perhaps then stands as the start of the end for Pink Floyd as a creative and writing ensemble.

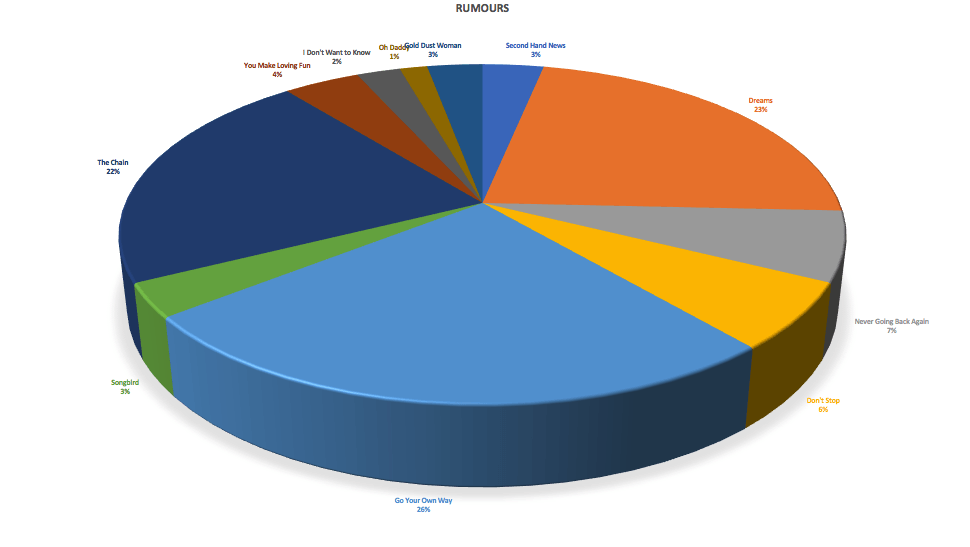

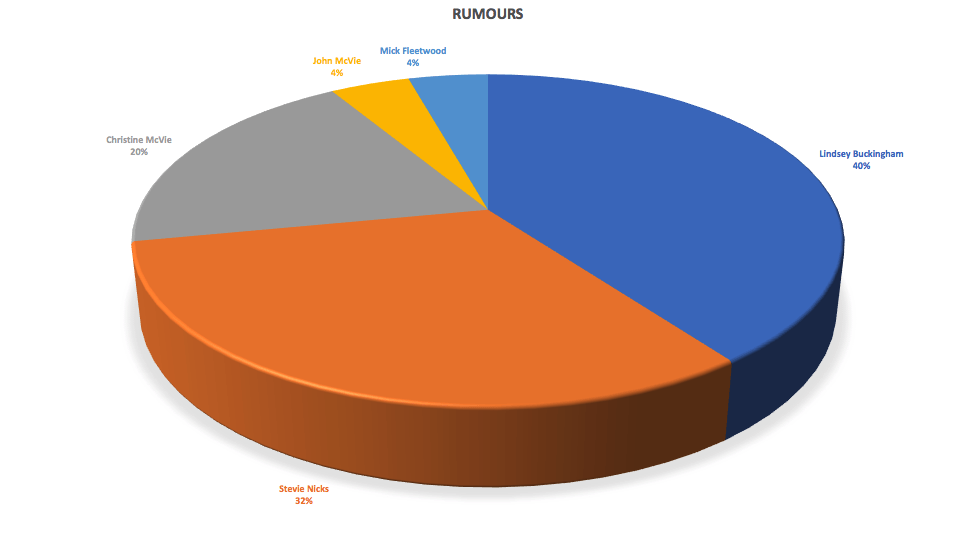

For Fleetwood Mac, however, Rumours was very much a group effort – perhaps fitting given it was created in a time on inter-band affairs. The previous album, 1975’s Fleetwood Mac, was the first to include Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks as members and two years later Rumours saw them coalesce musically if not always personally. In terms of the overall streams, Buckingham dominates as a writer, followed by Nicks and then Christine McVie. These three were all writing individually and McVie and Nicks each got four solo songs on the album to Buckingham’s three, but Buckingham edged ahead as ‘Go Your Own Way’ is the most streamed song from the album.

It is only on ‘The Chain’ that all five members (including John McVie and Mick Fleetwood, the only two founding members in the band at that stage) shared a writing credit. Indeed, it’s the only song on the album with multiple writers, the rest effectively working as solo projects in all by name for Stevie Nicks, Christine McVie and Lindsey Buckingham.

Conclusion

What is glaringly obvious is that mechancials are more elastic now in the streaming age and the spoils of success for an album are not evenly split. Despite the best intentions of National Album Day, the growing reality is that albums are not listened to as albums by the bulk of streaming consumers; but the idea of the “album” has not evaporated totally as the examples of 21 and 25 show – where the singles dominate but the other tracks on the albums get listened to on a relatively equal basis and contribute significantly to aggregate streams. Yet on some albums, it is basically about one of two massive hits that are now evergreens and everything else on the album wilts in their shadow. Ultimately for albums in the streaming age, one writer’s gain can only ever come at the expense of another writer.

1 comment

[…] Writers’ Bloc: How the UK’s Biggest Albums Break Down for Writers in the Streaming Age — synchtankltd.wpengine.com Eamonn Forde looks at the streaming performance of the 10 biggest UK albums as identified by the OCC and considers how streaming is impacting on them as both creative and commercial entities. […]