Eamonn Forde assesses the collateral damage associated with the rise of the new poly-writer reality, where processes and structures – already being pushed to the limit – are forced to play catch up.

It is no surprise to learn that more hands are involved in creating modern hits than was the case even in the relatively recent past. As a snapshot of this, we looked at the 10 biggest songs in the UK in 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000, 2010 and 2020 and analysed how many writers were involved in their creation. (We used the biggest hits of the first six months of this year but the full 12 months for each other year under analysis.)

- In 1960, two of the top 10 tracks of the year had a single writer and all the others had two writers.

- In 1970, most hits had one or two writers, with the exception of ‘Two Little Boys’ which had three (but which can no longer be played anywhere).

- In 1980, eight of the top 10 had two writers and the other two had a single writer.

- In 1990, songs mainly had one or two writers, with a few creeping up to three writers, although there was an anomaly with ‘Ice Ice Baby’ because of its sampling of ‘Under Pressure’, pushing the songwriting credits to eight.

- A decade on and in 2000 we are starting to see four and even five co-writers listed on the year’s biggest hits.

- By 2010, four or more writers are fast becoming the norm (with two of the year’s biggest hits having six sets of fingerprints on them).

- All this has carried into this year, where co-writers numbered between three and six but with a single exception – ‘Dance Monkey’ which only had a single writer.

In 2016, Music Week estimated that it took on average 4.53 songwriters to write a hit song and this number has been growing. Music Business Worldwide reported that, for the 10 most streamed tracks in the US in 2018, the average number of writers was 9.1, pointing out that Drake’s ‘In My Feelings’ had 16 co-writers, his ‘Nice For What’ had a staggering 21 listed writers and ‘I Like It’ by Cardi B/Bad Bunny/J Balvin had 15 writers (but if these three monster collaborations were removed, the top 10 average dropped to 5.57 writers). Helienne Lindvall, songwriter and chair of the Ivor Novello Awards, told GQ last year, “The attitude to what songwriting is has changed. It’s going up by half-to-a-whole songwriter every year and I think that’s going to continue.”

Against this, some acts are coming through where only one or two writers are involved in their hits. According to recent figures from Music Week, the average number of writers on top 100 singles fell 0.57 to 4.77 in 2019, the lowest level since 2016. Though a new breed of writer-artist – including the likes of Tom Walker, Billie Eilish, and Freya Ridings – has emerged in recent years, they would seem to be the exception rather than the rule. For now.

There is also a growing number of collaborators on songs, driven in part by the increase in the number of writers, with Chartmetric noting that it cuts across more genres than pop or hip-hop, with country and music from Latin and Caribbean artists also seeing more hands on the musical pump. This is what Chartmetric refers to as “collaborations as a new norm”.

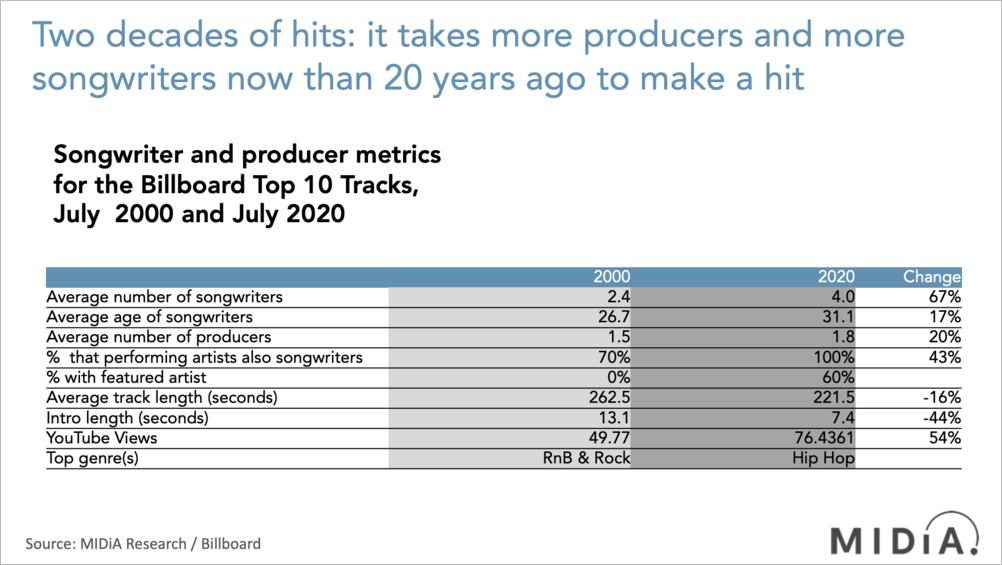

MIDiA lays this all out in stark terms, noting that in the Billboard top 10 tracks in July 2000, 70% of performing artists were also listed as songwriters on the track, but this grew to 100% in July 2020. That is all driven by the fact that none of the 10 biggest songs in 2000 had a featured artist but by 2020 this had jumped to 60%. There is a whole new power dynamic at play here where featured acts mean a broader audience reach for a song but it also sees the list of names on the songwriting credits grow exponentially.

We are also seeing this within K-pop, where many of the biggest hits by acts like BTS and Blackpink can see the number of songwriters involved start to nudge towards double figures. This all suggests an interesting new dynamic at play whereby songs, in order to be truly global streaming hits, need to pull together writers from multiple countries, where the resulting songs represent an interesting form of cultural hybridity and where, musicologically, they blend different traditions to create a new type of pop esperanto.

This all suggests an interesting new dynamic at play whereby songs, in order to be truly global streaming hits, need to pull together writers from multiple countries, where the resulting songs represent an interesting form of cultural hybridity.

None of this is a qualitative statement or judgment. This is not saying that hit songs today are somehow “lesser” because more writers are involved in their creation. It is just the reality of the modern songwriting business which, as illustrated in The Song Machine: Inside The Hit Factory (John Seabrook’s excellent 2015 book on the evolution/industrialisation of songwriting), involves the meeting of what we can call “section specialists” who deal in melodies, hooks or toplines. While this underpins the modern pop business, it also creates a number of licensing and accounting complications for that same business, especially when rights are split between multiple publishers and uneven shares make it hard to get a consensus when licensing opportunities arise.

This will become all the more pronounced as we enter what MIDiA Research has termed “the song economy” whereby certain older hits are becoming mini industries in their own right due to streaming, playlisting and syncs: the wind fills the sails of these songs decades after they were first hits, proving their staying power and cross-generational appeal; and the royalties fill the coffers of the few songwriters involved in their creation. If a hit from 2020 finds itself bedding into the public consciousness in 2060, the money will most likely have to be split in many more ways. Maybe it won’t buy the writers a new mansion each as they edge towards retirement age, but it might buy them a well-appointed bungalow each.

The issues under the song’s bonnet are also becoming more complex. Metadata, especially with regard to songwriting, has long been a conundrum in the digital age, but this is increasingly significantly in a poly-writer landscape. That is an obvious challenge for royalty payments; plus there is the ongoing issue where licensing becomes more convoluted and fraught the more stakeholders there are in a song. Clearing a song for synchronisation, for example, always had the tension between the label and the publisher (regarding what terms and rates they were pushing for), but when songs are split between a multitude of publishers too, that side of negotiations has grown sharply in complexity.

“Every co-writer has a say in licensing,” Lisa Alter, founding partner at legal firm Alter, Kendrick & Baron, told Synchtank recently. “You could find yourself with your hands tied, unable to get licences finalised because the licensee is chasing five, six, seven, eight other people.”

In the same piece, Alaister Moughan, founder of music consultancy Moghan Music, made a similar point. “The theory that you can increase sync [or other licensing] is made a lot more difficult when you’ve got six co-writers,” he said.

Both were talking about the market to sell catalogs (or shares of catalogs) and how those hits that involve a multitude of writers are seen by some investors as less attractive because their cut of future earnings is ultimately smaller if they are only buying into the publishing of one of the named writers.

Abby North, president of North Music Group, says she sees this trend continuing but believes that things are going to become even more complex if the average number of writers keeps creeping upwards – something which could have detrimental implications for the business being done here. “Managing five-to-nine, or more, rightsholders and their ‘truths’ regarding splits is very time-consuming and often leads to a delay in works being registered and royalties being collected,” she says.

“Managing five-to-nine, or more, rightsholders and their ‘truths’ regarding splits is very time-consuming and often leads to a delay in works being registered and royalties being collected.”

– Abby North, North Music Group

On top of this, she feels that publishing admin is going to become even more exhaustive to ensure that everything is tracked and attributed appropriately.

“In most cases, each administrator of a work will submit its own registration of the work to the various CMOs around the world,” she says of how the process works. “If splits aren’t agreed upon, if writer role codes are listed differently and if other data points are different in various registrations, the societies may not effectively manage merging of the registrations. As a consequence, some of the rightsholders may not receive royalty distributions.”

Music supervisors are also speaking out here, alluding to administration nightmares that might make them think twice about licensing certain songs or even working with particular genres.

“Hip-hop and rap is a little convoluted because of rights and licensing and then that spills a little bit into the pop world where there’s 15 writers and it’s just a very exhausting process,” said Jason Alexander, CEO & music supervisor at Hit the Ground Running during the BPI’s recent LA Sync Mission Webinar. “Invariably you find a 3.5% writer’s share that you didn’t know about till the last minute and that creates some problems.”

Speaking last year, music supervisor and founder of Grand Plan Entertainment Jen Ross told Pop Disciple that she will fight to include certain songs even if they have multiple writers – but she did not shy away from the extra workload that comes with this.

“Often, there are split disputes,” she said. “If you really, really want a song, you have to act as a mediator, be a bit of a detective to hunt people down and ask people to find a way to make it work. Sometimes, you can pull it off and sometimes you can’t. You have to wear many, many hats because nine times out of ten, it’s not a simple process.”

The downside of all of this is that, in a worst case scenario, music supervisors and licensing partners may have to take songs off their wish lists if the clearance process becomes too convoluted. The irony is that multiple writers can make these huge global hits but can also be a barrier to them having a lucrative afterlife in TV shows, films, videogames, adverts and more. Ultimately, not clearing rights properly or having to battle with incorrect data leaves both sides (rightsholders and those wanting to use them, from DSPs to Hollywood studios) exposed to litigation.

There does appear, then, to be an awful lot of collateral damage associated with the rise of this new poly-writer reality, where processes and structures – already being pushed to the limit due to billions of lines of streaming micropayments coming in – are forced to play catch up. The new songwriting craft is, it seems, fast outpacing the industry frameworks designed to support it.

The new songwriting craft is, it seems, fast outpacing the industry frameworks designed to support it.

There is, however, a new generation of services coming forward to try and bring order to this complexity, such as Auddly, SongSplits and Cosynd. They want to pin down songwriting splits at the source as songwriting teams can grow or shrink depending on the composition journey of the song. They are designed to work alongside the modern teams of writers and ensure there is an IP paper trail and that splits are agreed before a song is recorded and released to the world.

That helps cover off those who were proactively involved in writing a hit – the people who were literally in the room or at the other end of an ISDN line – but the “Blurred Lines” case and the precedent it set in legal terms is a whole new co-writing conundrum. In a complex legal battle, the heirs of Marvin Gaye were eventually able to get a cut of “Blurred Lines” as well as damages. This saw Mark Ronson have to add Rudolph Taylor and producer Lonnie Simmons (who wrote “Oops Up Side Your Head”) as co-writers of “Uptown Funk” as well as Taylor Swift including Fred Fairbrass, Richard Fairbrass and Rob Manzoli of Right Said Fred as co-writers on “Look What You Made Me Do” as it included an interpolation of their 1991 hit “I’m Too Sexy”.

Rather than these be the high-profile exceptions, there is a worry they could become the norm and modern hits – already bursting at the seams with multiple writers – might have to find space in the credits (and the spoils) for other writers. This, in turn, adds new accounting and licensing complexities to songs that were hardly admin-light in the first place.

“The clearance process also is a bit messy these days because the more writers, the more paperwork,” notes Karl Fowlkes, entertainment lawyer at The Fowlkes Firm. “A lot of paperwork can fall through the cracks. It’s important for producers, artists and songwriters alike to be as transparent as possible about outside contributions early in the process. Everyone looks bad when a contributor ‘forgets’ to mention someone helped them on their contribution to the song.”

North says that, regardless of how many writers are involved, it all hinges on the data. If it is poor to begin with, it slips a ticking time bomb underneath everything that follows.

“Good data management is absolutely crucial – and it doesn’t really matter how sophisticated the royalty system might be if the data is garbage.”

– Abby North, North Music Group

“Good data management is absolutely crucial – and it doesn’t really matter how sophisticated the royalty system might be if the data is garbage,” she says. “Royalty systems that include validation of identifiers, de-duplication algorithms and sophisticated matching algorithms do help tremendously.”

As Fowlkes says, “Everything revolves around technology, smart contracts, better algorithms that detect sampling or outside contributions. The education and information is out there, we as an industry need to accept the technology challenge and go headfirst. A lot of parties are fairly lazy when it comes to clearing records and maintaining splits. There are songs out there, where the splits are still in conflict years after the release. That can’t happen.”

“The education and information is out there, we as an industry need to accept the technology challenge and go headfirst.”

– Karl Fowlkes, The Fowlkes Firm

Slowly but surely the systems, processes and (crucially) technology are falling into place to make this all less of an administrative sinkhole than it could be; but the onus is on everyone in the chain – from creation to exploitation – to work with (rather than against) all these complexities and ensure they are front and centre of everything they do. It might seem terribly pessimistic, but anticipating the worst is perhaps the best route for success. As the cliché has it, fail to prepare and prepare to fail.