How do you put a price on music? Bas Grasmayer looks at the past, present and future of pricing digital music.

Price vs. value

When approaching price points as a representation of the value of a product, nobody’s going to feel satisfied with the price of music. A song is worth more than a dollar. And more music than you can ever listen to is worth more than $10 per month.

Yet to price a song at its value is an impossible task. To the creator, a song can be worth more than any sum of money. To potential listeners, the value differs and changes over time. Your all-time favourite song has more value to you now, than it did when you first heard it.

Pricing strategy

Much of the pricing we’re used to seeing now has to do with reducing barriers and came to prominence among widespread piracy and industry revenue decline. The general industry strategy has been to reduce friction and invent price points that produce as little friction as possible.

Downloads pricing

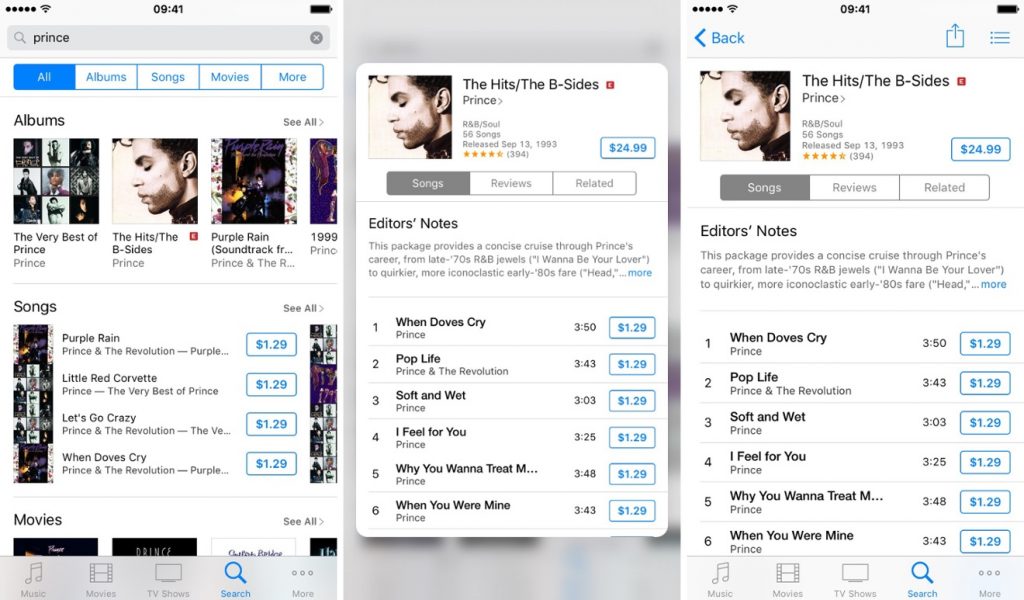

The first pervasive instance of this, was the $0.99 per song model utilized by iTunes. Although not pioneered by Apple, the combination of the price point, software and hardware reduced a lot of the common friction at the time. For a long time Apple resisted variable pricing, and then budged creating different price tiers to change pricing based on demand.

More recently, Apple created a special Great 69¢ Songs section to iTunes, which labels started to utilize to get their songs charting. Normally hit songs would be available for $1.29, but for selected songs the price point is lower. It’s a costly strategy though, between $2,000 and $10,000 a week, with the majority of tracks losing money.

And while track sales are down 25% this year, streaming is up by as much as 50% in some markets.

Streaming pricing

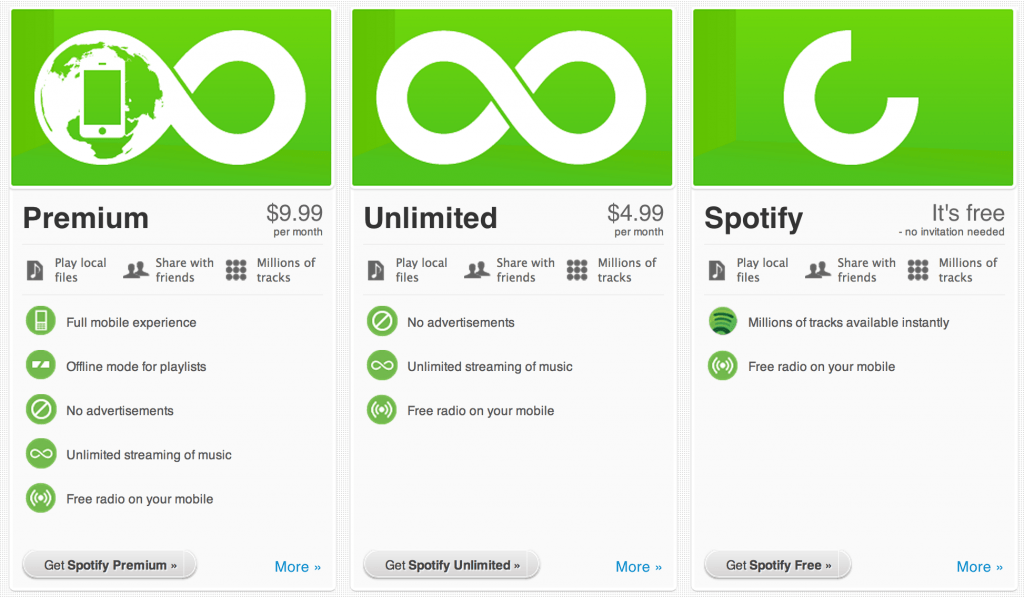

In markets in the West, streaming pricing is usually divided into these tiers:

- Free, ad-supported: this can be on-demand or internet radio.

- Semi-interactive: think radio that gives you some control, like Pandora, Last.fm.

- Mid-range: streaming apps with a limited feature set.

- Premium: the $9.99 / month model.

$9.99

You’ll hear a lot of complaints about the $9.99 price in music business circles. The most-heard argument is that it caps music lovers’ spending to a low price point. The price point, indeed intended to cater to music lovers, was originally aimed to peel people away from pirate services. It has been successful in reducing piracy, with the European Commission finding in 2015 that every 47 streams lead to one fewer bootlegged track. The research also takes into account streaming’s cannibalisation of downloads, leading to a conclusion that the model is ‘revenue neutral’ for the music business.

$0

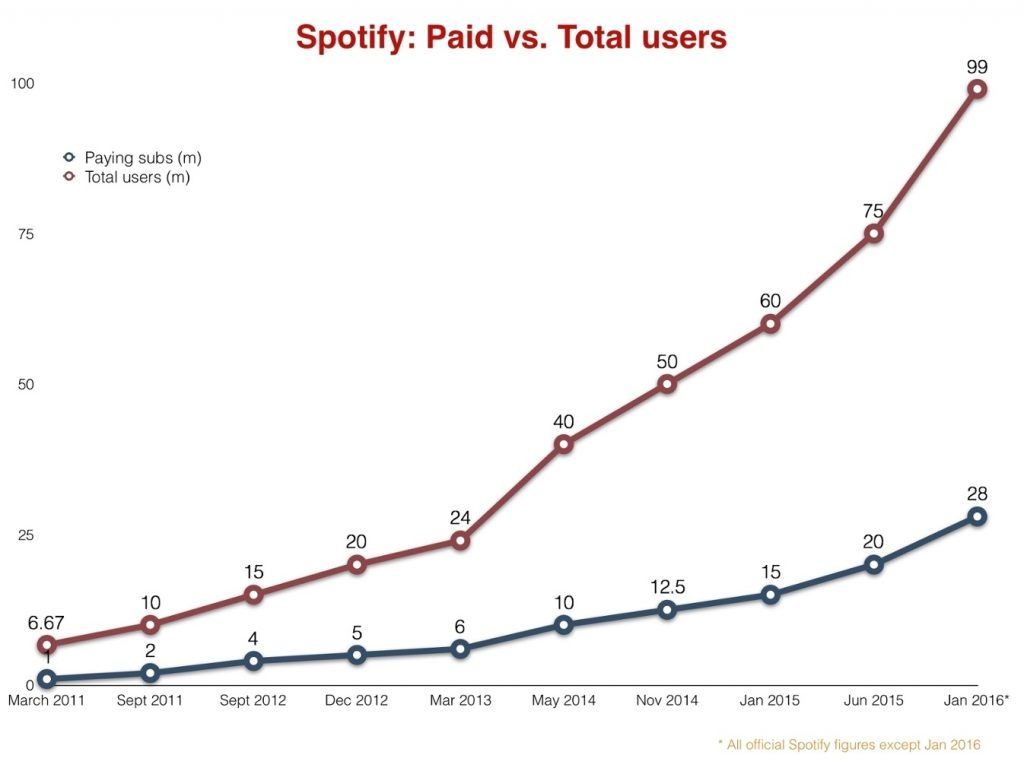

In streaming services, the free tier is often explained as another way to get people away from piracy and into their ecosystem. Earlier this year, Tim Ingham reported that Spotify was converting roughly a quarter of their free users to the paid tier. Its rapid subscriber growth in recent months was in part due to a promotional $0.99 offer for 3 months, according to music industry analyst Mark Mulligan.

(Chart source: Music Business Worldwide)

He points out that the promotional offer has led to a free-to-paid ratio of 37%, meaning it converts better than the standard freemium model (from $0 to $9.99), speculating that it might spell the end for freemium. Other services, like Apple Music or TIDAL, already lack a free tier. And with Spotify’s newest batch of subscribers netting at $3.09 per month, perhaps the $9.99 tier is due for an overhaul as well.

Mid-tier pricing

Pandora made big news by announcing a $4.99 price tier launched this month. It remains to be seen whether the product offers enough, as right now it seems like it’s basically radio with offline syncing and more skips. Still, it provides an interesting price point to look closely at how it converts free to paid users.

For a ‘radio plus’ feature, it feels like a premium price point. As Spotify’s recent numbers have shown, premium pricing is not enough to convert mainstream music listeners to paid users. Other price points are needed.

The now defunct Bloom.fm had an interesting take on the problem. Offering users free, unlimited radio streaming and discovery for free. For £1 per month, users were able to store 20 tracks from radio and listen to them again. For £5, this was extended to 200 tracks.

When I was working on Zvooq, a music streaming service in Russia, we built an app called Fonoteka. It was designed as a companion app for the ad-supported web service and was supposed to exist inside an ecosystem of apps targeting specific music behaviours. It allowed users to download the albums they discovered on the web service to their phones. 3 albums a day for $1 per month. 7 albums a day for $2. Take into account that due to lower purchasing power, music prices in developing markets like Russia are often roughly half of what they are in more developed markets.

A similar app is MTV Trax, which lets users download & listen to the most popular hits – refreshed on a daily basis. Price points differ. As an indication, in Spain they charge €0,89 per week.

The shift to mainstream pricing

The impending market saturation of the $9.99 price point, with Spotify and Apple Music leading the way, creates cause for new models. With the steady decline of downloads, the fear of cannibalising that market will decline, too. In the next few years, we’re going to be seeing more experiments with lower price points, below $5 per month, to bring in mainstream consumers.

The offering of these apps will be limited compared to the $9.99 price point, yet they’ll need to feel ‘better than free’. Expect the micropayment model we see with successful games to make its way to music apps, or the season pass model so common with premium games. Expect apps to focus on doing a particular thing really well, whether that’s curating a genre, offering access to labels or artists like SupaPass, or monopolizing very specific music behaviours.

From personal experience, I expect these services to pop up in emerging markets, because labels are less hesitant to license new models there — there’s less money to lose if they accidentally end up undermining the $9.99 model.

In developed markets, expect more super premium offerings to raise the $9.99 cap for the more hardcore music fans. This comes in the form of direct label or artist subscriptions, as offered by Kickstarter’s Drip, Bandcamp, and SupaPass. It comes in the form of ‘high definition’ subscriptions like TIDAL’s $19.99 tier, though perhaps the product offering there needs to be expanded. Offering other extras inside premium music streaming services can help increase the cap, although Apple Music really dropped the ball with this by not giving its Connect feature enough love.

Keep in mind: if you’re reading this, $9.99 likely seems reasonable. Or perhaps even too low, compared to the CD era. Most mainstream consumers just won’t make the jump at that price point, and so far had to be pulled in through super discounts, family plans and bundling deals with mobile operators.

As the streaming market matures, we need to keep moving up the curve and into an increasingly mainstream audience. They don’t need all the music in the world – they just want something good, now.

This creates an exciting space for targeted apps to monetize specific audiences and create way more revenue streams from currently unmonetized audiences.

We’re at the start of a new phase of the streaming landscape.

1 comment

[…] 150M paying subscribers). Two decades later and many of the same philosophical debates about the price and value of music continue. Meanwhile, gaming, an industry that faced the same piracy issues as the music industry, […]