With famous musicians and industry executives continuing to express their discontent over the current streaming royalty rates for songwriters, Eamonn Forde takes a look at the situation and explains why the solution is not as simple as it appears.

You wait ages for a major name in the music business to argue that streaming royalties for writers could be a lot higher – and then two come along at once.

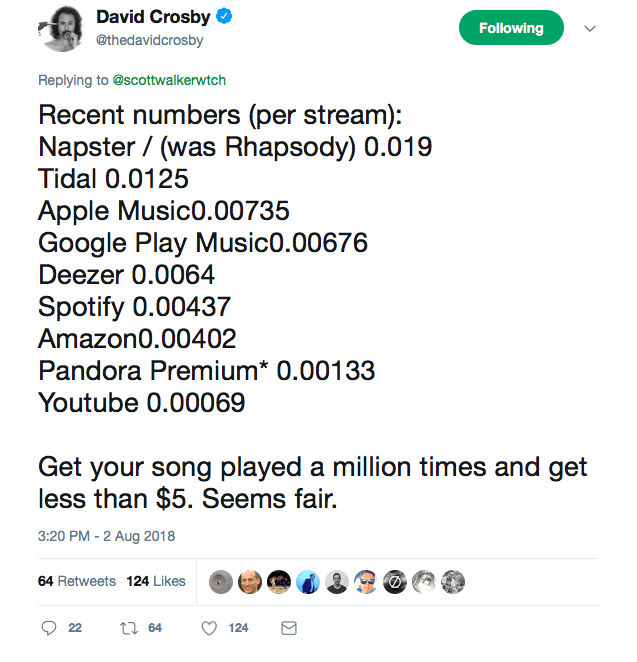

At the start of August, David Crosby – who had enormous success in the 1960s with The Byrds and even greater success in the 1970s with Crosby, Stills & Nash (and occasionally Young) – published on Twitter exactly what his streaming payments were from all the major digital services. He ended his tweet with a sarcastic flourish. “Get your song played a million times and get less than $5,” he wrote. “Seems fair.”

Less than a fortnight later, Jody Gerson, the CEO and chairman of Universal Music Publishing Group, spoke to the Wall Street Journal and argued that, while streaming might be growing the recorded music market again, “the fees are not where we want them to be” and that means publishers and writers still “get paid much less than the labels”.

The recorded music market has been rising (slowly) in recent years, finally turning around the long decline since the millennium. With at least two of the major labels selling the bulk of their Spotify shares, it is something of a golden time for labels. Streaming has pulled off what downloading never could – offsetting the decline in physical sales.

Within this, however, is a serious knock-on effect for mechanical royalties.

“Streaming has pulled off what downloading never could – offsetting the decline in physical sales. Within this, however, is a serious knock-on effect for mechanical royalties.”

Looking at the numbers quoted by Crosby in his tweet, they were both incredibly specific but also incredibly vague. He gives the per-stream rate of nine different services, with Napster paying the highest (0.019) and YouTube paying the lowest (0.00069); but after that it gets somewhat ambiguous. We can presume the numbers are quoted in US dollars, but it is not clear if this is based on royalty payments as an average across all songs he was involved with or if they were based on the same track but across different services.

Also, the “$5 for a million plays” does not stack up. Even on YouTube, which offers the lowest-paying rate, a million plays would have, based on his quoted numbers, generated $690. Meanwhile a million plays on Napster would have generated $19,000. But that major miscalculation should not detract from his wider argument that streaming royalties for writers are not quite the gold rush some presume.

On the publishing side, it is important to note that for the biggest hits he was involved in the recording of, Crosby was often not the writer or had to share writing credits with others. Based on Spotify’s public play numbers, we can see that on the biggest hits from the 1964-1967 era of The Byrds (before Crosby first left the band), none were written by Crosby. ‘Turn! Turn! Turn! (To Everything There Is A Season)’ was written by Pete Seeger, ‘Mr Tambourine Man’ was written by Bob Dylan, ‘Eight Miles High’ is split between Gene Clark, Roger McGuinn and David Crosby and ‘My Back Pages’ was another Dylan cover.

For Crosby, Stills & Nash’s biggest hits, ‘Suite: Judy Blue Eyes’ was written by Stephen Stills, as was ‘Helplessly Hoping’, while ‘Southern Cross’ is a song is credited to Stills, Rick Curtis, and Michael Curtis. For the Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young era, ‘Ohio’ was written by Neil Young, ‘Our House’ was written by Graham Nash as was ‘Teach Your Children’. Of course, there are a plethora of songs that Crosby wrote, but it is worth remembering the full context in cases like this as sometimes quoted figures for publishing income are split between multiple writers.

This leads into a broader point in Gerson’s criticisms of the publishing royalty structure around streaming – that not only do writers today have to write chart blockbusters to get enough streams to make a good living, they are often having to share writing credits with several other writers. So even if they were involved in a huge streaming hit, the publishing could be divided multiple ways. Five or six writers on a song is not uncommon and this can, especially if samples have been used in the recording, go into double figures.

The rise of the multi-writer – something John Seabrook traces in his 2015 book, The Song Machine: Inside the Hit Factory Book – is the new normal in the top 40. On Ed Sheeran’s recent Divide album, for example, there are over 20 different writers involved in different songs on there. Gerson, while not specifically talking about Sheeran or any other hit artist, argued that the proliferation of co-writers “is going to hurt the economics of being a songwriter”.

As the divide between what is and isn’t a single today has been blurred, the economics of mechanicals has changed – and this was something Gerson was keen to point out in her interview with The Wall Street Journal:

“When I first came into the industry, you could write a cut on a big album, like for Whitney Houston, and it would sell a lot of records, and you could make a lot of money as a songwriter,” she said of the era of the CD and LP. “But unless you’re writing hit singles or you have pieces of songs on enormous numbers of streamed product, it is very difficult right now.”

– Jody Gerson, Chairman and CEO of Universal Music Publishing

That is unquestionably true, but there is an argument that the boom of the CD in the 1990s created an artificial bubble for both record labels and publishers. Labels could make more money by selling CDs at a significantly higher price than LPs or cassettes (while often giving a reduced royalty to recording artists); publishers and writers also benefitted as the mechanicals were split equally across all the songs on the album – be it a massive hit or, frankly, some padding that was stuck on the end of the album and rarely played.

This is now redundant in the streaming age. The blessing of streaming is that good songs will be played over and over for years to come; the curse is that terrible songs will sink immediately. There’s a dual dynamic here that we can maybe start to think of as the long tail and the short fail.

The bigger issue, however, remains: namely that writers and publishers feel they should be paid more for their songs on streaming platforms. There are three main ways this can be addressed:

1) Record labels agree to a lower cut of streaming royalties and that is passed on to writers and publishers;

2) DSPs like Spotify agree to a lower cut of revenue from subscriptions and ads and that is passed on to writers and publishers (and maybe also labels);

3) Consumers pay more for a subscription and that is shared among services, labels and publishers.

Points 1) and 2) are effectively about keeping the total pie the same size but merely changing the way it is sliced. Achieving this boost for writers would mean labels reducing their share (extremely unlikely) or services taking a lower cut (which, considering their tight margins and mounting losses, is currently inconceivable).

That leaves point 3) as the most apposite solution for not just publishers but also for labels and services. But it comes with enormous risks. The subscription sector settled on the £9.99/$9.99/€9.99 price point in the early 2000s with the arrival of Rhapsody and the legal incarnation on Napster – and it bedded in even further with the arrival of Spotify and Apple Music and their charge into the mainstream. There are discount options like bundled deals with mobile operators or family plans, but the only attempt to go beyond the ossified £9.99 price has been in courting the audiophile market by charging £19.99 a month for improved audio.

There is something of a pricing stalemate here. No service is willing to break from the pack and charge more, even though the price has effectively remained the same for close to two decades. If inflation was factored in, according to the Office for National Statistics composite price index, what cost £9.99 in 2000 is the equivalent of £16.33 today. Yet streaming subscriptions have not moved in line with inflation when pretty every other consumer product has.

“There is something of a pricing stalemate here. No service is willing to break from the pack and charge more, even though the price has effectively remained the same for close to two decades.”

While Netflix has subtly adjusted its subscription fees recently, no streaming service has made that leap of faith – even though they could justify it as moving in line with the inflation rate.

Until that happens, the chances of songwriters getting paid more per stream than they currently are is on hold. They are, sadly, the collateral damage of a pricing deadlock.

3 comments

Great summation. further covered in the “Dissecting the Digital Dollar” books published by the Music Managers Forum in the UK (www.themmf.net).

The first questions to ask anyone quoting figures like these are:

Are these payments for masters or publishing? And if the latter is the payment for mechanicals or performance income?

The first solution is never going to happen. The majors make far more margin on masters income than publishing and they want to keep it that way.

Artificial bubble indeed.

As for paying more, subscription services will need to segment the market at some point. The base product would be $9.99. Higher priced tiers would offer more value…exactly what I don’t know. Exclusive content? Early access to some songs? Access to alternative versions or recordings (like Spotify sessions)? Better voice capabilities? It’ll be tough, though. The current trend is discounting to gain subscribers, not price increases to benefit rights owners.

But even if some good number of people paid twice as much, would Crosby be content with his royalties? I’d guess not. 2x almost nothing is still almost nothing.

As for a solution, I have nothing to offer at this time.

“tight margins and mounting losses,” AND the fact that Spotify and Apple (but especially Spotify) have also to answer to shareholders.